A table for four at Chula – an introduction to ‘The Empty Child’

In February 2004, at an Indian restaurant in Hammersmith, four colleagues meet to chat and exchange notes. The restaurant is called ‘Chula’ and the people sat around the table are celebrating being asked to write for the new series of Doctor Who – which was returning to the BBC (TV Movie not withstanding) for the first time since 1989. They are:

Mark Gatiss – best known at this point for ‘The League of Gentlemen’ or in the Doctor Who world for several unlicensed spin-off videos, his Virgin New Adventures and BBC Past Doctor Adventure books (especially his first – Nightshade) and a handful of Big Finish Audios. Unsurprisingly he has been given a story of Dickens, ghosts and séances.

Paul Cornell – long-term fan and the creative force behind many of the best and most influential Virgin New Adventures – including ‘Human Nature’ – which consensus has as the best Doctor Who book. Given the emotional core at the heart of his books – he has been assigned the story of Rose meeting her Father.

Rob Sherman – another long term fan and playwright – he is best known at this point for his much lauded Big Finish contributions – ‘The Holy terror’, ‘Scherzo’ and particularly the ‘Chimes of Midnight’. His story is to be based on another highly thought of BF story – ‘Jubilee’ and may or may not at this stage be featuring the Daleks!

And last, but definitely not least Steven Moffat – a well known figure in fan circles, but ‘Curse of Fatal Death’ and one short story aside, he has yet to really contribute to Doctor Who. He was originally amongst the group of writers approached by Gary Russell to write for Big Finish when they won the licence, but left the first meeting when he realised that Paul McGann wasn’t on board – wanting to write new Doctor Who. At this stage he is best known for ‘Coupling’ – his sitcom which I absolutely love and his highly regarded children’s show “Press Gang’.

They are a very astute choice of writing team by Russell T. Davies and all are steeped in Doctor Who and its history. What is interesting is that of all them, it will be Steven Moffat who needs the least guidance and re-writing from Russell. There are plenty of drafts this time around, but after the ‘The Empty Child’, Russell assigned him a script editor and pretty much left him to get on with it.

Steven ended up writing episodes 9 and 10 from a basic idea from Russell. I thought it would interesting to look at the pitch from Russell that Steven Moffat was given:

World War II

Two part London in wartime, the blitz, blackout, sirens, Nazi spies, kisses in the dark and stiff upper lips…

True story: a gang of kids lived wild on the bombsites of London. They were evacuees who’d run away from abusive homes, or the only survivors of their families. Fugitives from the police and the army, they’d hide by day and scavenge by night. They were only free during air raids, when everyone else would hide’ they’d run through the streets, surrounded by the fires of war. With dogfights above the city, spent bullets would hail down from the sky.

But the kids have a legend, a ghost story they would tell each other. Of something else scavenging at night… Something which darts over the rubble impossibly fast, which looks like a child … until you get up close…

It’s an amazing time for Rose – recent history and yet so distant. The fun of wartime spirit, undercut by knowledge of what’s happening to the world.

And it’s a time for romance as Rose falls for captain Jack Harkness. Except Jack seems to know something more than he should – and as the nightmarish chid creature attacks and we head for another cliffhanger…

Captain Jax

… as he is better known is a futurist soldier from another world – the captor of the child creature here on Earth to track it down,

Out of his English disguise, Jax is everything the Doctor’s companion should be – or so it seems to Rose. Lively, funny, sexy and arrogant, he struts about, armed to the teeth with laser-guns, bandying interstellar information with the Doctor. The two men get on a treat. (And perhaps Jax has heard stories of the fate of the Time Lords). Rose feels intimidated – even more so when, the adventure ends, Jax comes on board to travel with the…

Some ideas survive, some things fundamentally change – the relationship between Jack, Rose and the Doctor for one, but there is no mention of the main reason why this story is being covered in this thread – the body horror and transformation. Anyway this time around I am going to cover this one episode at a time, so:

Oh and the name of that Indian restaurant became the name of an alien race, whose hospital ship becomes the centre of a strange and rather horrific epidemic in the middle of wartime London as playgrounds and work places around the country rang out to the phrase ‘Are you my mummy’?

‘Are you my Mummy?’

‘Please, mummy. Please let me in. I’m scared of the bombs, mummy. Please, mummy.‘

In the introduction to this story, I used the original story outline from the series one pitch document. This was aimed at showing the BBC the size and shape and ambition of the show and Russell’s ‘vision’ for it. It also provided guidelines for the other writers, once the series was confirmed as expanded to 13 episodes. At the time Russell said that for copyright reasons he had to be originator of each of the story ideas. Given all of that, it is interesting that this script feels very much like Steven Moffat’s vision for the show – like a window opening up on an alternative timeline. At this point we really didn’t have a template for what this vision might be – there are some themes that he would return to later, but at this stage the snappy dialogue at least would be familiar to those who had watched ‘Coupling’ or even ‘Curse of Fatal Death’. This different take on the show also appears in the pacing of the two-parter, the depiction of Rose and especially in the writing of Captain Jack – it feels like some serious writing talent has been imported in and given a bit more freedom than usual to show us what their version of the show might be like. Rose is written very differently here I think – she feels like a Steven Moffat character, less of a soap/popular drama character and more like one of the leads from Coupling – much smarter and wisecracking (‘give me some Spock’, ‘scan for alien tech’) – these words don’t feel like Rose – actually they feel like they aren’t from Russell – they are very much from Steven Moffat.

You don’t need to know anything about the old series to enjoy ‘The Empty Child’ – but in some ways this feels to me a far more natural evolution than Russell’s scripts had up until this point – like a Robert Holmes script buffed up by someone who is very clever and with a modern sensibility. It is still my favourite story since the show returned – the only new series story to make my top 5. If ‘The Unquiet Dead’ gave me hope that there might be something in the new series for me and ‘Dalek’ and ‘Father’s Day’ re-enforced that – this story told me that it was possible to unconditionally love it. I will always be grateful to Steven Moffat for that. After a lot of series one being tooled to appeal to the widest possible popular audience, ‘The Empty Child’ just feels brilliantly, thrillingly like ‘Doctor Who’ – clever, scary, funny – just buffed up for a 21st Century Saturday Night audience.

Of Children and gas masks

‘Massive head trauma, mostly to the left side. Partial collapse of the chest cavity, mostly to the right. There’s some scarring on the back of the hand and the gas mask seems to be fused to the flesh, but I can’t see any burns. ‘

A child in a gas mask – I’m not sure that there is a more evocative symbol of war and it’s effects on a civil population. The gas mask itself runs through the British national psyche, more especially with regard to the First World War – a symbol of the horrors of war where chemical weapons (chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas mostly) were used in the trenches. During the Second World War, this symbolism extended to the general population, including children and it is a potent symbol of the corrupting effects of war on innocents. Gas masks have been used to symbolise war before in Doctor Who before – at the start of ‘Genesis of the Daleks’ as the soldiers are gunned down in slow motion and during the gas attack on the Kaled trench and in Deadly Assassin in the nightmarish matrix sequences of episode 3 where a gas masked soldier and horse walk through the mist towards the camera. I suppose it is the dehumanising effect on the human face that makes them so scary here, combined with that powerful symbolism of ‘total war’.

These shorthand images for the evils of war and especially the impacts on a civil population tend to involve children and to a lesser degree animals, to such an extent that it almost became a cliche – photo journalists carrying around a small child’s shoe to place on top of a mound of rubble in Beirut or another similarly war torn city. In some ways it is the ultimate expression of the corruption of innocence by war. The image of a child in a gas mask also conjures up the spectre of one of the most feared strains of warfare – the use of chemical weapons – an escalation even beyond ‘conventional’ warfare on a population. Gas masks were issued to the whole population at the start of the war by a government fearing the effects of chemical attacks on the cities of Britain. I remember talking to my Dad and his older brothers, who were children during the May blitz which destroyed huge swathes of Liverpool, including their street and they had gas masks that were supposedly designed to appeal to children, to make them less scary – like a game – he had a Mickey Mouse gas mask – rather than reassuring, they look absolutely terrifying– see the image below.

I can’t find any reference where anyone explains where the image of the child, fused with a gas mask comes from – it isn’t in Russell’s original pitch. It is an extraordinarily imaginative idea – I can’t really think of a similar piece of work that uses images of similar form of body horror. A story where this forms the central image – a young child whose injuries are so bad that amongst the head trauma and partial collapse of the chest cavity, the gas mask has actually fused to his face, when you stop to think about it is horrific on a number of levels – real injuries that could be sustained by a child in an air raid. The fantasy body horror layered on to of this takes this further again – the idea that the gas mask is actually made of flesh and bone and that the child is ‘empty’ – nothing behind the mask is incredibly powerful – but to extend that to the child spreading this condition via touch is very, very clever and really scary.

Despite that powerful horrific central image, the story is brilliantly balanced by the dazzling, clever, funny script, the excellent cast and the introduction of the irrepressible John Barrowman as Captain Jack Harkness. Oddly for a story set in World War II Russell’s main tone word was ‘romance’, the romantic view of the blitz. So amongst the horrors of war and the children living in the bombed out remains of the city we also have the romance of dashing RAF officers and underground drinking clubs – an image lifted from Dennis Potter’s “The Singing Detective’ – all to balance out the grimness. This is also reflected in the direction, cinematography and lighting – which are quite beautiful. James Hawes directs this with real panache and more than a hint of film noir, the tilt of the camera indicating strangeness. Look at this scene where the phone rings as the Doctor and Nancy are in the hall looking at the child at the front door.

Also at this stage, the grading is used far more subtly than later, the palette is dark – but light is used really effectively – giving the work a warmth and romance. It all looks consistent – set at night, but with soft lighting – which contributes to a unity of tone across the piece even as it switches between horror, action and comedy.

I will cover the ‘romantic triangle’ between Captain Jack, Rose and the Doctor next time when I review ‘The Doctor Dances’. Briefly here though there are scenes which still look wonderful now as Rose flies across London hanging from a barrage balloon and is rescued by Jack. The dialogue between the two fizzes and is very much the Steven Moffat of ‘Coupling’. The shots of Rose and Jack dancing to ‘Moonlight Serenade’ on top of an invisible spaceship tethered to Big Ben during an air raid are quite magical – which other show could do that? All of this nicely counterpoints the horror of the story and the grim existence of the street children very nicely – making this one of the best balanced stories since the show returned.

If Rose feels slightly different than usual (her look of lust at Captain Jack is very much her!) – the Ninth Doctor however is captured perfectly. Chris responds to this and is superb across both episodes. Steven has read the script on the time war and we get:

CONSTANTINE: Before this war began, I was a father and a grandfather. Now I am neither. But I’m still a doctor.

DOCTOR: Yeah. I know the feeling.

So we start to get the ‘Lonely Angel’ that we would see further in ‘The Girl in the Fireplace’. The Doctor has a natural empathy with the child:

DOCTOR: What’s this, then? It’s never easy being the only child left out in the cold, you know.

NANCY: I suppose you’d know.

DOCTOR: I do actually, yes

Special mention to Florence Hoath who is fantastic in this – she was my favourite female guest actor in this series and I am still amazed that she didn’t go on to great things, it is still one of my favourite performances since the show returned. The child actors in the ‘Marxism in action or a West End musical’ scenes are all pretty good too. Again I will come back to the aspect of the story when I cover the next episode.

‘Human DNA is being rewritten by an idiot’.

NANCY: You mustn’t let him touch you!

DOCTOR: What happens if he touches me?

NANCY: He’ll make you like him.

DOCTOR: And what’s he like?

NANCY: I’ve got to go.

DOCTOR: Nancy, what ‘s he like?

NANCY: He’s empty.

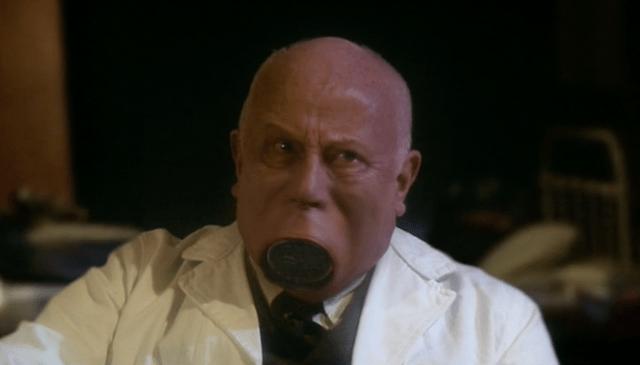

If Florence Hoath was my favourite female actor of series one, then Richard Wilson must go down as one of my favourite guest performances, almost a cameo, in the last 57 years. He is absolutely superb as Doctor Constantine.

DOCTOR: You’re very sick.

CONSTANTINE: Dying, I should think. I just haven’t been able to find the time. Are you a doctor?

DOCTOR: I have my moments.

CONSTANTINE: At first. His injuries were truly dreadful. By the following morning, every doctor and nurse who had treated him, who had touched him, had those exact same injuries. By the morning after that, every patient in the same ward, the exact same injuries. Within a week, the entire hospital. Physical injuries as plague. Can you explain that? What would you say was the cause of death?

DOCTOR: The head trauma.

CONSTANTINE: No.

DOCTOR: Asphyxiation.

CONSTANTINE: No.

DOCTOR: The collapse of the chest cavity

CONSTANTINE: No.

DOCTOR: All right. What was the cause of death?

CONSTANTINE: There wasn’t one. They’re not dead

The sequence where Constantine becomes increasingly ill and then transforms is one of the most horrific, identifiable and effective sequences in the whole of Doctor Who. This is how Steven Moffat describes this sequence in the script:

‘The Doctor stares at him in horror. Constantine is now staring at him, weirdly all sense gone from his eyes…

And then his mouth is being forced open, by something inside. A flash of metal. And the nozzle of a gasmask starts to force its way out of his mouth…. On the Doctor horrified, fascinated. The skin of Constantine’s face is pulling back, stretching – slowly, horribly morphing into a gasmask.

It’s over in seconds. The man on the chair is now identical to every other body in the room. He slumps, lolls… On the Doctor, staring: what the hell happened there?? He steps away form him, looks round at the identical others. He clutches his head, despairing at himself.’

The sound effect of the cracking and stretching was removed from the broadcast version, but re-instated for the DVD release and is really quite horrible. It is clear that Constantine is in a great deal of physical pain as he transforms. Also the physical transformation is bad enough, but this is combined with the loss of self (putting the emptiness into ‘empty’) – he becomes just like the others. The images comprising this sequence will be posted separately after this post, due the image posting restrictions. For a number of children of family and friends this sequence alone was too much and they stopped watching the show for a while. Sad though that might be, part of me feels quite happy about that. I like to imagine Robert Holmes would be sat on a cloud somewhere – actually I doubt Mary Whitehouse would allow him through the pearly gates – she’s probably been haranguing him for 15 years now, while he smiles nonchalantly through a cloud of pipe smoke fondly remembering the old days when he would routinely ‘scare the little buggers to death’!

One other point though, this isn’t the cliffhanger – I always forget that. It instinctively feels like it should be – like Scaroth’s reveal or Linx removing his helmet. Here it is a prelude to the multiple cliffhangers – which is a trick used in a number of old series stories, but most often in the Holmes/Hinchcliffe era. We have Nancy corned by ‘The Child’ and The Doctor, Rose and Jack surrounded by the ‘empty’ gasmask ‘zombies’ (including Constantine) in the hospital ward. The tension is really ratcheted up by this and this was the point at which in series one I realised just how much I missed both cliffhangers and also the time afforded by a two-parter to develop a story properly.

‘The Empty Child’ is an extraordinary opening episode and introduces us to someone who will, over the course of his first 5 stories will establish himself as one of the programme’s truly great writers. It balances thrills, action, romance, with some of the most stomach churning and inventive body horror that I have ever seen. Who comes up with an idea like people being converted into gas mask zombies? Or ‘Physical injuries as plague’ as Dr Constantine tells us? Within the context of Doctor Who this is borderline genius and for the first time in a very long time I really couldn’t wait until the following Saturday.

Learning to ‘Dance’

‘Go to your room, I’m really very angry with you

I honestly think that this is one of the greatest resolutions to a cliffhanger in the show’s history. What really makes it work for me is the very rapid switch from horror and menace to humour, to pathos as the child (and then all of the others) incline their head to one side and walk off sadly. So, after the absolute horror of the transformation of Constantine and the menace of being touched and transformed or made ‘empty’ – this is then undercut by the Doctor and a moment of humour, which only really works because we suddenly realise how sad this is, that the child in amongst the physical trauma is still in part just a small child, alone and looking for it’s mother – the comedy is just a grace note on the run from menace to pathos. It is so cleverly written, beautifully played and directed. The realisation that the child is still ultimately just a child who has suffered horribly is cemented by Nancy slumping against the wall plaintively crying ‘Jamie…’ after her cliffhanger is resolved. Horror, the absurd/uncanny, comedy and pathos – that is Doctor Who for me all wrapped up here. On reflection, I like this resolution much better than the later Steven Moffat ploy of switching episode two to a different location or time or doglegging off in a different direction.

In the review of the first episode, I really wanted to concentrate on the body horror and transformation sequence – however that is far from the whole story – it would be less satisfying if it were. First of all we have the remarkable Nancy (brilliantly played by Florence Hoath) – looking after the street kids of London – finding food for them and acting as a de facto Mum. At this stage we think that Jamie – ‘the child’ is her brother and that her loss is the thing that is driving her to help the other dispossessed children. On top of that, the story fulfils its obligations within the season by introducing Captain Jack. Steven Moffat does this brilliantly – Jack is like the intersection in a Venn diagram between Russell and Steven – he could easily have been created by either – so it works very well here and unlike the depiction of Rose, feels seamless. In John Barrowman they just have a star – between his charismatic performance and the quality of the writing, Jack arrives fully formed and fits in perfectly.

‘She was hanging from a barrage balloon, I had an invisible spaceship. I never stood a chance.’

A fair bit of this episode is also concerned with the developing triangle between Captain Jack, The Doctor and Rose. Steven Moffat is pretty explicitly saying that ‘dancing’ is sex and the Doctor definitely does dance – fitting in with reference to being a Father and Grandfather in the last episode. I often go back to an article from 1999 in DWM 279 called ‘We’re going to bigger than Star Wars’ – where Russell, Steven, Paul Cornell, Mark Gatiss, Gareth Roberts and Lance Parkin talk about how they would bring back the show (still very hypothetical at this point). It makes fascinating reading – but oddly on this subject it is Gareth Roberts who suggests an emotional arc of the companion fancies the Doctor – not Russell or Steven. Steven talks about the show very much in terms of appealing to children – making it the best children’s TV show again and then appealing to the child within the adult audience secondly. In contrast what we get here is very much Steven still in ‘Coupling’ mode – Jack as ‘Captain Innuendo’ and the Doctor and Jack comparing the size of their ‘sonic devices’ in an act of one-upmanship to impress Rose. This is presumably to appeal to adults and teenagers, whilst the kids are wrapped up with the horror and thrills.

‘He saved my life. Bloke-wise, that’s up there with flossing. I trust him because he’s like you. – except with dating and dancing.’

‘I’ll tell you what’s happening. You forgot to set your alarm clock. It’s volcano day’.

So, Rose has already been swept off her feet by Jack – wined and dined on top of a spaceship tethered to Big Ben. They’ve exchanged first impressions in a clever use of the psychic paper. The Doctor however is rather less impressed with Jack – especially when he realises that he albeit inadvertently caused the whole problem. This triangle between Captain Jack, Rose and the Doctor – however brilliantly done, when I actually think about it, is just odd. Rose is supposed to be 18 (that comes from Russell’s pitch document – not sure if it is ever contradicted?) – she is in love with The Doctor and he falls for her – really, after 900 odd years? Is this Doctor’s mid-life crisis? Is he just lonely and lost after the conclusion of the Time War? At least the Eighth Doctor chose a grown up, Reinette felt like a much better match in ‘Girl in the Fireplace’ and River Song ends up as saucy older (actually younger) woman to Matt’s Doctor. I don’t know – the general public loved it – so Russell was obviously right, it just doesn’t stand up to much examination beyond an initial emotional response. The leads play it all really well and the dialogue fizzes and is very funny, which I think stops you from thinking about it too much – but it feels a bit more like Steve, Jeff, Patrick, Susan, Jane and Sally than Doctor Who.

‘There are people running around with gas mask heads calling for their mummies, and the sky’s full of Germans dropping bombs on me. Tell me, do you think there’s anything left I couldn’t believe?’

Anyway, back to the main plot. Like Robert Holmes, Steven is very good at the scary set piece – and there are a series of these across the story. There is another cracker here – the child has earlier been sent to its room by the Doctor. The Doctor, Rose and Jack are listening to a tape recording of Constantine talking to the child – but the tape runs out and they can still hear the child’s voice – they are in the room that the Doctor has sent it back to. Similarly Nancy handcuffed next to a soldier who is about to transform or a last minute filler scene with a typewriter still tapping away ‘Are you my mummy’ long after one of the street children has stopped typing – or the ringing of the TARDIS phone – or the toys coming to life – just like Bob Holmes might have done, ‘borrowed’ from Close Encounters! These moments really work well and the story has real momentum and scale in between the quieter moments – such as Rose and Nancy discussing the war or the Doctor gently uncovering the truth about the relationship between Nancy and Jamie.

‘These nanogenes, they’re not like the ones on your ship. This lot have never seen a human being before. Don’t know what a human being’s supposed to look like. All they’ve got to go on is one little body, and there’s not a lot left. But they carry right on. They do what they’re programmed to do. They patch it up. Can’t tell what’s gasmask and what’s skull, but they do their best. Then off they fly, off they go, work to be done. Because, you see, now they think they know what people should look like, and it’s time to fix all the rest. And they won’t ever stop. They won’t ever, ever stop. The entire human race is going to be torn down and rebuilt in the form of one terrified child looking for its mother, and nothing in the world can stop it!’

Is this ‘malfunctioning tech, in this case the nanogenes from the chula ship, caused the whole thing’ storyline a first for the programme? I’m sure it can’t be – the nearest story I could think of was ‘The War Machines’ or maybe ‘The Green Death’? I’m sure I must be missing something – there are other stories where technology is appropriated for someone else’s cause – ‘Robot’, ‘Robots of Death’ etc. Here the whole plotline is basically technology getting something wrong because of the incomplete data being available. It is something that the new series returns repeatedly to a after this story. I can see why it is attractive as a theme – it avoids having a ‘villain’ per se, instead it is just an accident, a tragedy – something that happens with the proliferation of technology – something we understand today – where technology is much more part of our every day life, as opposed to being restricted to just scientific or military bases. I suppose it is also part of a general move away from monsters or ‘evil’ villains – some of which seems to be problematic in the 21st century. The middle of the 20th century had plenty of real examples of what feels instinctively as evil and hence I think the generation that grew up in that era and those that followed immediately after found the straightforward morality of stories of good versus evil appealing. Or maybe I am wrong?

Oh, come on. Give me a day like this. Give me this one.

Everybody lives, Rose. Just this once, everybody lives!

So, what could have been one of the darkest of stories ends on a joyous note – everybody lives, even better – amputated legs grow back and pensioners feel years younger. And this is entirely appropriate here. This most damaged of Doctor’s – the one after the one who fought the Time War and committed genocide on a grand scale. He just deserves a happy ending. And this one makes sense – it works on two levels – the emotional response of a child re-united with it’s Mum and is acknowledged for the first time, but also in terms of plot logic – Nancy as the child’s mother gives the nanogenes the genetic template to work off to realise what a complete human should look like and enough to correct the changes they have made to the others based largely on guesswork. That is smart, clever and uplifting. It isn’t just a woolly ‘everything goes a bit glowy and everything is alright again’ or ‘love makes everything better’ ending – it is all of those things, but crucially for me it makes sense, is given a proper rationale and it works very well because of that. It also feels instinctively more satisfying than the original ending, which was to involve Jamie’s German-speaking father.

These scenes are also joyously played by Christopher Eccleston. Apart from ‘Dalek ‘and possibly ‘Parting of the Ways’, this is his best performance as the Doctor – he is given more to work with here than usual. In some ways that is a real shame – you have one of the best actors in the country and have him chase a space pig (the first scene he recorded) or dealing with farting politicians. That is all part of being the Doctor – but a few more heavier, meatier scenes to showcase what a fine actor he is would have been nice.

And at the end of all this we have the coda as the TARDIS acquires a new crew member. After being depicted sat astride a German bomb suspended in stasis in mid-air (some more Holmes-style borrowing, this time from ‘Dr Strangelove’) Jack is rescued from his exploding ship and after some more ‘dancing’ and a bit more innuendo about his sexuality we’re off back into time and space – well Cardiff anyway! That would be my luck , all of time and space to choose from and I’d up somewhere I can get to on Great Western train in and hour and a half!

‘The Empty Child’ feels old and new at the same time. For me it feels like equilibrium – or the still point (I’m watching Snakedance!) between the two runs of the programme. It has plenty that feels new – sex/romance, Jack’s omni-sexuality, the malfunctioning tech resolution, smart snappy dialogue, the emotional ending and the scale of Rose flying across London during the blitz – but all wrapped up in a classic Who piece of body horror, with the gas mask people lurching slowly towards our heroes, the threat of making them ‘empty’ – of losing their self and free will, scary cliffhangers and a pacing that allows the story to breathe. It is the perfect new series story for me and I love it with a passion.