‘So this is one of the last paintings Van Gogh ever painted. Those final months of his life were probably the most astonishing artistic outpouring in history. It was like Shakespeare knocking off Othello, Macbeth and King Lear over the summer hols. And especially astonishing because Van Gogh did it with no hope of praise or reward.’

From the beautiful opening image Wheatfield with crows brought to life, Vincent and the Doctor is suffused with the foreknowledge we have about Vincent’s life and death. The wheat field scene and the painting it is based on, pre-figure his eventual suicide, aged 37, in a wheat field in July 1890 (Auvers-sur-Oise rather than Arles in this story, he died later of the wounds at his lodgings), the painting is from the same month and is possibly his last. Genius, mental health problems and suicide, it is not without reason that this is the only Doctor Who story, to my knowledge, that came with its own helpline.

‘He’s drunk, he’s mad and he never pays his bills.‘

Well Vincent meet the madman with a box who eats Fish Custard and the girl who waited 12 years for him, had 4 psychiatrists and kept biting them… Throughout this piece they make an engaging trio, such that I have difficulty imagining this working with another Doctor (McGann or Eccleston maybe at a push?) and companion. Matt’s gently daffy Doctor works wonderfully here with Tony Curran’s brilliant Vincent. Vincent finely attuned to the world of internal pain, has no trouble in identifying Amy’s loss (Rory in the previous story), even when she can’t identify it herself. Her love of his work, fiery temperament and fiery hair make them a natural pairing. Her joy at seeing the past come to life and meeting the man and settings behind the paintings she loves is very infectious. The script deftly balances the exploration of the issues that Vincent has with good humour and bonhomie:

Doctor: And you’ll be sure to tell me if you see any, you know, monsters.

Vincent: Yes. While I may be mad, I’m not stupid.

Doctor: No. Quite. And, to be honest, I’m not sure about mad either. It seems to me depression is a very complex

Vincent: Shush. I’m working.

If it pulls its punches when it comes to the infamous ear incident, it does face up to the Vincent’s depression when it needs to, specifically in the scene were Vincent is curled up on the bed:

DOCTOR: Vincent? Vincent! Vincent, can I help?

VINCENT: It’s so clear you cannot help. And when you leave, and everyone always leaves, I will be left once more with an empty heart and no hope.

DOCTOR: My experience is that there is, you know, surprisingly, always hope.

VINCENT: Then your experience is incomplete. I know how it will end. And it will not end well.

DOCTOR: Come on. Come out. Come on, let’s go outside.

VINCENT: Get out! You get out. What are you doing here? What are you doing here?

DOCTOR: Very well. I’ll leave. I’ll leave you.

Richard Curtis – sometime purveyor of fine comedy (Blackadder) and sweetly (some would say overly) sentimental films (Four Wedding, Notting Hill, Love Actually) and driving force behind Comic Relief (kudos to him for that and his work on third world debt cancellation), is on slightly alien territory here. Curtis shares this season with another writer primarily known for his comedy and new to Doctor Who – Simon Nye. In my view, the series should attempt this every so often and if it doesn’t entirely work sometimes, maybe that is the price to pay for getting new and different voices into the show? It is something that Russell tried to do unsuccessfully with Paul Abbot and Stephen Fry. Steven Moffat repeated this to some degree with Neil Gaiman (although his knowledge of the form and details of the show is far greater than Curtis) and Frank Cottrell-Boyce.

The nominal plot here – the lost, invisible Krafayis, is not what interests me about the story – superficially it provides a reason to visit Vincent, a monster for the kids and a moment of pathos as we hear its last thoughts in its death scene. The original idea of the creature being part of a pair, killing itself out of sorrow and loneliness after the death of its partner may have worked better (or maybe not), mirroring the road that Van Gough himself was on. As it is, despite maybe not being the best realised creature since the show returned, an invisible monster that only Vincent can see is a suitable ‘physical’ embodiment for Vincent’s depression – mental health, the invisible illness and as such works well thematically.

One other aspect that works really well, is the insight both the script and visuals give us into the world as Vincent sees its:

It’s colour. Colour that holds the key. I can hear the colours. Listen to them. Every time I step outside, I feel nature is shouting at me. Come on. Come and get me. Come on. Come on! Capture my mystery

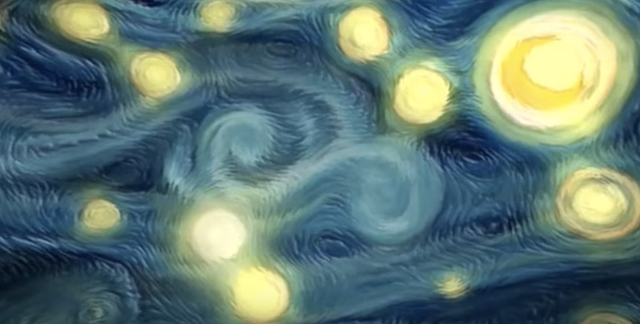

Vincent’s relationship with colour made me think of the Doctor’s relationship with time, he sees the world in a very different way to the rest of us (including the Krafayis). This is principally shown through the sequence where Vincent, Amy and Doctor lie back and view the night sky through Vincent’s eyes as it magically transforms into Starry Night. This is not just one of the finest sequences broadcast in ‘Doctor Who‘, but for my money anywhere. The script and the visuals combine to deliver a quite wonderful moment:

VINCENT: Hold my hand, Doctor. Try to see what I see. We are so lucky we are still alive to see this beautiful world. Look at the sky. It’s not dark and black and without character. The black is in fact deep blue. And over there, lighter blue. And blowing through the blueness and the blackness, the wind swirling through the air and then, shining, burning, bursting through, the stars. Can you see how they roar their light? Everywhere we look, the complex magic of nature blazes before our eyes.

DOCTOR: I’ve seen many things, my friend. But you’re right. Nothing quite as wonderful as the things you see.

VINCENT: I will miss you terribly.

The direction from Jonny Campbell is stunning at times (the cut from Vincent painting Wheatfield with Crows to the painting hanging in the Musee D’Orsay springs to mind), as is the cinematography of Tony Slater Ling and the work of the art department. The latter’s work in Trogir is brilliant – transforming a local café beautifully into the Cafe Terrace on the Place du Forum or the recreation of the Bedroom in Yellow House. As for Amy, illuminated by sunflowers in the morning sun, it is ‘as bright as sunflowers‘.

And so to the episode ending (love the TARDIS covered in posters by the way), if we have been given an insight into Vincent’s view of the world, it is time for him to be given an insight into ours and how it views both him and his work. At the Musee D’Orsay in Paris, he comes face to face with his legacy in one of the most moving scenes in Doctor Who. Very few forms of storytelling could do this – only those with time travel at their core – show a genius, unrecognised and unloved in his lifetime that he is loved and venerated in the future. To be able to offer at least partial redemption for a lonely, sometimes depressed individual. That is rather lovely and even after many viewings never fails to reduce me to tears.

You’ve turned out to be the first doctor ever actually to make a difference to my life.

At the end of this extraordinary story, I think quite unlike anything attempted in ‘Doctor Who‘ before or since, a seemingly re-invigorated Vincent disappears off to face his demons and his eventual journey to the wheat field in Auvers-sur-Oise. The nearest comparison that I can think of is probably the rejuvenated Dickens in ‘The Unquiet Dead‘, still heading towards a fatal stroke and still failing to finish Edwin Drood, but that doesn’t match the emotional impact or intensity here. Amy, whilst sad that she could not change the past and save Vincent, at least gets to see Vincent’s gratitude for her efforts to make his life better (For Amy, Vincent). As Doctor Black (the ever wonderful Bill Nighy) says with a tearful Vincent in earshot:

‘Van Gogh is the finest painter of them all. Certainly, the most popular great painter of all time. The most beloved. His command of colour, the most magnificent. He transformed the pain of his tormented life into ecstatic beauty. Pain is easy to portray, but to use your passion and pain to portray the ecstasy and joy and magnificence of our world. No one had ever done it before. Perhaps no one ever will again. To my mind, that strange, wild man who roamed the fields of Provence was not only the world’s greatest artist, but also one of the greatest men who ever lived.’

I will leave the last words to Vincent himself:

The sadness will last forever