Introduction – A room with a view

‘Ghost Light’ might be set in Perivale Village in 1883, but really, I think its heart is in Oxford, in the writings of Charles DoDoDodgson, of Alice Liddell, The Oxford Dodo, of Soapy Sam Wilberforce, T.H. Huxley and ‘The Great Debate’. Oxford and its surroundings are somewhere I know pretty well. Despite not really being Oxford material, I studied Conservation (the ecological/wildlife sort) at the university as an adult learner, finishing my dissertation seven years ago. I was an outsider really, as were most of my fellow post-grad students. Even if I had evolved across those years into a more typical Oxford student in the manner of Josiah Smith, which I never quite did despite putting the hours drinking in the ‘Eagle & Child’, it takes more than that to be accepted into university life proper. Whatever, I spent 4 years researching and writing about everything from climate change, sea level rise, ecological systems and extinction. The course was also about practical ecological surveying and conservation management and I spent many a day sinking into the mud along Thames meadows, in disused quarries and wetlands. This will all become relevant during the main review – I promise!

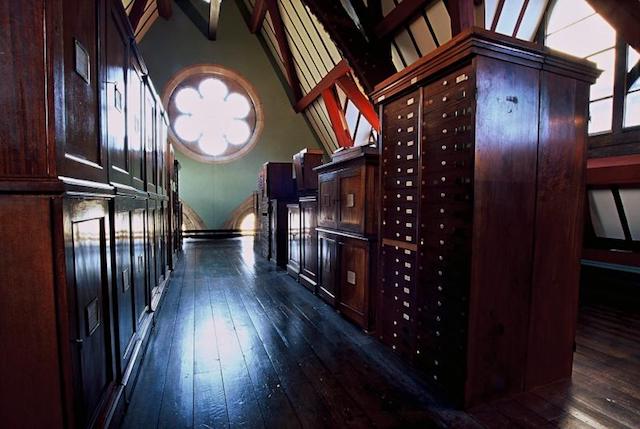

For four years I had access to a world of scientific journals, but more than that to the resources of the University Natural History Museum, the Herbaria, the Botanical gardens, the Bodleian and the Radcliffe Science Library and the outdoor resources of Wytham Woods. It was a whole world of scientific learning, stretching back hundreds of years. Being able to see specimens collected from around the world by the likes of Linnaeus, Darwin and Hooker – their hand-written annotations in the margins was thrilling in a way that I can’t quite describe. Oxford’s Natural History Museum (OUNHM) is a particular world of wonder – of wrought iron and stone, neo-gothic, wooden display cases, stone pillars, statues of the great and good of science, Swifts nesting in the tower in summertime. It feels a bit like an airier, lighter version of the McGann TARDIS! Amongst its treasures are the sadly mummified remains of the Dodo that inspired Lewis Carroll to include it in Alice, a Great Auk egg, a Passenger Pidgeon, Carolina Parakeet, the New Zealand Huia – all sadly long gone. As is Megalosaurus Bucklandii – the first identified Dinosaur, discovered near Oxford and described by the Reverend William Buckland.

My favourite place in Oxford is contained within these walls. Though these days it is a pretty non-descript store room, rather appropriately it’s use has evolved over the years – it is now known as the Huxley Room. It now contains some beautiful old wooden cases mostly containing collections of pinned insects. And yet, walking into this space was really thrilling, as thrilling as walking through the police box doors and stepping onto the Capaldi TARDIS set! This is no ordinary storage room though – in a former life this was a meeting room and was the site on the 30th June 1860 of what has in retrospect become one of the most important meetings in scientific history. This occasion was a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science – one where one of the main protagonists (actually it is more correct to say two) was missing, his case fought by proxy by his friends and allies. This has in retrospect gained a reputation – the moment of victory of the rational, progressive and scientific over the supernatural and its version of the history of life on this planet stretching back no more than a few thousand years. In some quarters, despite more than a hundred and fifty years of overwhelming supporting evidence this debate about evolution by natural selection still happens. Some people refuse to evolve and change – ‘Light’ would love them.

As ever though, the truth is more complex than the legend of this event dubbed ‘The Great Debate’. Contemporary accounts differ considerably on what exactly happened and ’Soapy’ Sam Wilberforce – the Bishop of Oxford and leader of the opposition against Darwin and ‘On the Origin of the Species’ was himself a serious figure and capable speaker – in contrast to the Reverend Mathews in ‘Ghost Light’. He was the son of the man responsible for the abolition of slavery, he had a first in Mathematics, was a member of the Royal Society and had a scientific background. Wilberforce had also been coached before the meeting by the great comparative anatomist Richard Owen (the man who gave us the term ‘dinosaur’), a religious man, whilst also a brilliant scientist and founder of the Natural History Museum in London, he doesn’t seem to have been a very pleasant man – driven, ambitious, ruthless and not above appropriating the work of others and using politics to destroy rivals – he also detested Darwin’s theory. Taking up Darwin’s case was the naturalist Thomas Huxley and Darwin’s friend the great botanist Joseph Hooker.

The crucial moment of the debate – at least in hindsight and with some embellishment is the moment when Wilberforce asks Huxley (the absent Darwin’s ‘bulldog’) whether ‘it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed descent from a monkey?’. Huxley is reputed (although the exact words are disputed) to have said something to the effect of:

‘If then the question is put to me whether I would rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means of influence and yet employs these faculties and that influence for the purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion, I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape.’

In the legend, ladies are supposed to have fainted and Wilberforce was defeated in a stroke. In practice, it seems that the words of Hooker, the eminent botanist and friend of Darwin were also important in winning the day. Although Wilberforce clearly viewed Huxley as his main opponent.

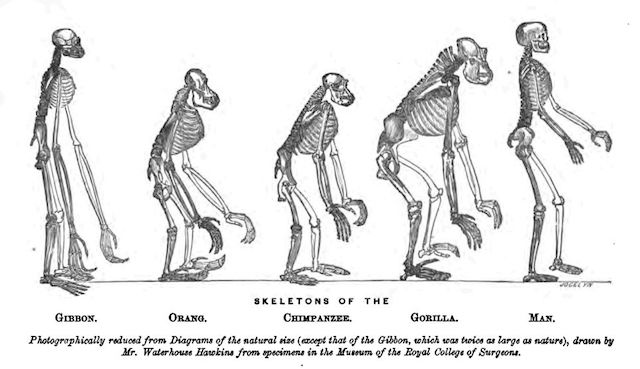

So why is this important to ‘Ghost Light’? Well at its core the story is this debate writ large – the Reverend Mathews (himself from Oxford) representing a refusal to believe in change, in evolution – Josiah (and his husks – stages in his own personal evolution) and Control are living evidence of that change. Light (‘the Recording Angel’) doesn’t deny the change – he just doesn’t like it and wants it stopped so that he can finish his catalogue. Marc Platt was an archivist for the BBC at the time of writing the story – endlessly documenting radio programmes – which I think is where this aspect of the piece comes from. The pivotal moment, at least in the legend of the ‘Great Debate’ plays out in ‘Ghost Light’ as the Reverend Ernest Mathews is shown in the cruelest way his true ancestry – becoming an ape in a display case – losing the debate and his life. This image of Huxley’s ‘Place of Man in Nature’ in reverse:

It is a gruesome end for an unlikeable character, in the real world at least ‘Soapy Sam’ got to live another day – Darwin and Wallace (by proxy), Huxley and Hooker won the argument and change defeated stagnation. The meeting room fell into disuse, was eventually split into two – aptly the Huxley Room and the Wilberforce Room and life moved on, everything changes, for good or ill, sometimes we have to just adapt to it.

The evolution of Ghost Light

There are few stories that are based on the concept of change more than ‘Ghost Light’ – not only does it take evolution, speciation and extinction as its central concept, but it is an idea itself that evolved from something that was originally quite different. Changing from a story about the Doctor’s house and family on Gallifrey to a story about an ecological survey on a planetary scale and Darwinian evolution in Victorian England. On the way merging the idea of the ‘Great Debate’ (covered in the introduction), with Social Darwinism and the concept of the Victorian English Gentleman as evolutionary endpoint or at least the species fittest to survive and flourish in the world of Victorian England and the British Empire. It also absorbs a smattering of literary influences from ‘The Hunting of the Snark’ and the ‘Alice’ books of Lewis Carrol, George Bernard Shaw (Pygmalion), Conan-Doyle (‘Redvers had some stories. The pigmies from the Eluti forest lead him blindfold for three whole days through uncharted jungle. They took him to a swamp full of giant lizards like giant dinosaurs. Do you know, young Conan Doyle just laughed at him’) and H. Rider Haggard to the cast of bizarre characters of Mervyn Peake’s ‘Gormanghast’ books.

Marc was a ‘Doctor Who’ fan, working at the BBC documenting radio programmes for the archive, who had grown up with the show during the Hartnell era. He had lots of clever ideas for stories which he sent to the BBC Doctor Who production office over the years – to Robert Holmes, Douglas Adams, Christopher H Bidmead and Eric Saward, each one getting closer, only to have the recipient move on before commissioning him. Then one of them reached Andrew Cartmel (season 26 really was the last chance saloon for getting your script made) and he liked what he read and invited Marc in to discuss his ideas for what neither knew would be the final season of the original run of the show. The idea that made it through was called ‘Lungbarrow’ – a story which was to take the Doctor back to his ‘worst place in the universe’ – his home and family on Gallifrey. The story was eventually vetoed by JNT after a long period of development and Marc instead switched the location to a Victorian House and made it Ace’s ‘worst place’ – Gabriel Chase, the house she burned down in the 1980’s. So, ‘Lungbarrow’ rather appropriately evolved into ‘Ghost Light’. Everything changes.

‘Ghost Light’ would ultimately prove to be Marc’s sole contribution to the TV series – he would have written for series 27 (an Ice Warrior story adapted as ‘Thin Ice’ by Big Finish). He does get an onscreen credit for providing the inspiration for ‘Age of Steel/Rise of the Cybermen’ and really should have got one for ‘The World Enough and Time/The Doctor Falls’. If like me, you like his work for Big Finish, many of his preoccupations apparent in ‘Ghost Light’ are also evident in ‘Loups Garoux’ or ‘Spare Parts’ or ‘Paper Cuts’, ‘The Silver Turk’ or ‘The Butcher of Brisbane’. Like Robert Holmes, he is the master of building and populating worlds, which however strange they might be, feel real and are drawn in some detail, giving them verisimilitude and depth.

Another similarity to Holmes is ‘Ghost Light’s’ treatment of death, displaying a similar love of the grand guignol. The more I think of it, ‘Ghost Light’ gets away with some of the most macabre deaths in the history of the show. Think of Holmes’s ‘Terror of the Autons’ – McDermott consumed by a plastic sofa, Farrel Snr strangled by a troll doll or of poor Goodge miniaturised and placed in his own lunchbox. Here we have the Reverend Mathews transformed into an ape (eating a banana in the process) and placed in a display case (a monkey house without room for two), Inspector MacKenzie reduced to primordial soup and served at the table (‘the cream of Scotland Yard’ almost feels like prime Holmes), a maid dismembered by Light – he holds up her severed arm and Mrs Pritchard and Gwendoline re-united forever – turned to stone by Light – never changing. To my mind this outdoes even the darkest moments of Eric Saward’s stewardship in the hue of its black comedy. An awful lot of the inhabitants of this strange world are ‘sent to Java’ in the most macabre ways.

Marc Platt also obviously has a love for the natural world. ‘Loup Garoux’ draws on the post-collapse Amazonian desert (Rosa – ‘Jaguar Girl’ with the whole host of the extinct species of the forest in her head) and the complex social world of werewolves, ‘Spare Parts’ the dark 1950’s austerity Britain of Mondas with its cyber-converted police horses and electronic caged birds, or ‘The Butcher of Brisbane’ with the bizarre experiments of Greel’s world such as packs of talking Dingoes. Here we have Great Auks, Emu’s, Birds of Paradise and Lady Amherst’s Pheasants, the Peppered Moth changing with industrialisation and Neanderthal man with his stories of the Pleistocene – Mammoths and Cave Bears. At the season when the ice floods swamp the pasture lands, we herded the mammoths sunwards to find new grazing.’. All of this wrapped up in a house whose current ‘owner’ indulges in the Victorian gentlemanly pursuit of natural history and collection of zoological specimens.

Aside from the themes of evolution, change and the literary trappings, ‘Ghost Light’ also explores the underbelly of Victorian life, of empire, social class and climbing the ladder – both evolutionary and in terms of status in the case of Josiah. Scratch the Victorian veneer and something nasty’ll come crawling out. We have Redvers and his tales of the dark continent and Josiah’s aspirations of meeting the Queen Empress, later to ‘hunt the crowned Saxe-Coburg’. Whilst trying to buy the Doctor’s expertise to rid himself of control, that great Thatcherite dictum ‘Victorian Values’ is evoked, lest we forget this is the late 80’s and that woman is yet to fall from power. Even Control wants to become a ladylike. This isn’t Darwinian evolution, rather a different kind – one with direction towards the perfect endpoint of development – the Victorian gentry, born to empire. More of which later.

On reflection the script for ‘Ghost Light’, well it strikes me and this is with the benefit of 30 years of hindsight, that it is actually quite a straightforward story told in a complicated almost wilfully obscure and obtuse way with a bizarre cast of characters and some arcane dialogue that give it an air of mystery and complexity that the core story doesn’t really have. In particular, the characters almost feel like cast of a Victorian drawing room murder mystery or Cluedo, albeit one put through a filter with the settings marked dial weird to 11 – we have the butler, the severe housekeeper (Mrs Hudson?), the vicar, the inventor, the explorer (albeit one in a dissociative fugue state – ‘Redvers kicked over his traces and lost himself in the bush. Lord knows if he’ll ever find his way out again.’) and the bumbling policeman (Lestrade?).

The basic story – an alien comes to survey all life on Earth, bringing a survey agent who evolves into a ‘local’ species best fit to complete the survey and a control that doesn’t change to enable the change to be measured. The survey controller sleeps for thousands of years and the survey agent runs amok, getting ideas above his station, ideas of ruling an empire and even the control starts to want to change – it is the story of ‘lunatics taking over the asylum’. Since the controller has slept for so long, the original survey data is now hopelessly out of date and he’s not happy. That is about it. I’ll examine whether and why this is so confusing in another piece, suffice for now to say that many people were baffled upon its transmission and some continue to be to this day.

As a production, ‘Ghost Light’ is probably the most assured of the Seventh Doctor era, albeit against scant competition for that honour – much as I like a lot of the era, consistency of production isn’t one of its key attributes. So much so, that you almost marvel at the fact that the BBC decided to cancel the series just as the production team worked out what it was they needed to do to make the whole thing work! They had finally evolved into an organization that had everything you need to make terrific ‘Doctor Who’ – a Doctor who could waltz through adventures veering from clown to dark genius, his plucky, headstrong, all action assistant – a group of capable, if green script writers with good ideas and a script editor who backs them and has finally worked out what works for a BBC production and within the context of the show. Add in Music by the very capable Mark Ayres and a director that seems to know what he’s doing. That’s right – time to cancel it!

It is a cliché to say that the BBC at this point in time really knew how to do historical costume drama – but it is also true – all the stops are pulled out to make this a rich, handsome production. The direction from Alan Wearing is neat, with some of the set pieces feeling almost choreographed. The music is also terrific, if too high in the mix, making the production overly noisy – a common fault in the era to my mind. Mark Ayres soundtrack fits the production beautifully – it really adds to the atmosphere of the piece. I really struggle (or rather shudder) to imagine another version scored by Keff and his magic disco machine going Stock, Aitken & Waterman over all of this Victorian, gothic splendour.

Another triumph is the casting – the performances are superb, one of the best ensemble casts of the whole original run. Sylvia Syms is almost unrecognisable as Mrs Pritchard, at least when you know her more as the beautiful young women of ‘Ice Cold In Alex’ or ‘Victim’, but here she is wonderfully severe, cracking only in her final scene as she and her daughter are turned to stone by Light. It is one of the creepiest performances in the show – probably since Lillias Walker as Sister Lamont. We also have excellent comic turns by John Nettleton as the Reverend Mathews, Frank Windsor as Inspector MacKenzie , the ever wonderful Michael Cochrane as the Victorian explorer Redvers Fenn-Cooper and Carl Forgione as the Neanderthal butler Nimrod. These performances though are pitched perfectly for this sort of piece – played for real, but with enough of ‘size’ to match the oddness of the storytelling. Ace also gets a young female counterpart in Katherine Schlesinger (niece of director John Schlesinger and Peggy Ashcroft apparently) in a confident turn as Gwendoline – a curiously sensual performance. And then we come to three survey team members John Hallam as Light, Sharon Duce as Control, who makes a good job of a difficult role and a delicious grandstanding performance from Ian Hogg as Josiah Smith. Hallam’s performance as Light maybe the weakest of them, but it has an odd, ethereal, sing-song feel to the performance, which I think works, but I could see that it might not for others.

If ‘Ghost Light’ was the first story I’d seen of Sylvester as the Doctor, then I would have assumed he was a popular character actor and instantly understood why he was given the role. He really has come an awfully long way from ‘Time and the Rani’ – when he felt more like a children’s entertainer than an actor. He still has his limitations, but he makes a highly effective Doctor by this point I think. His relationship with Ace is interesting, it works largely because of the obvious friendship between the two actors, but the other aspect – the manipulative, partly controlling, partly teaching, partly liberating aspect, I’m not sure what I think of that. On reflection, I think it is at least different, a development on the Doctor Leela ‘Pygmalion’ relationship of Season 14, that was then abandoned before reaching its obvious conclusion. However, the ‘manipulation’ of Ace should probably have ended with season 26, the excesses of the New Adventures in this respect aren’t really to my taste and often make for painful reading. We do however, get some lovely exchanges between the pair as a result of this aspect of the script – most famously:

ACE: Don’t you have things you hate?

DOCTOR: I can’t stand burnt toast. I loathe bus stations. Terrible places, full of lost luggage and lost souls.

ACE: I told you I never wanted to come back here again.

DOCTOR: Then there’s unrequited love, and tyranny, and cruelty.

ACE: Too right.

DOCTOR: We all have a universe of our own terrors to face.

ACE: I face mine on my own terms.

With this Doctor, it isn’t always those grand speeches and dark master plans though that grab the attention though. It is rather the quieter, more reflective moments that shine. In this story a favourite moment of mine is when he stops to talk to a cockchafer on his hand:

‘All civilisation starts with hunting and foraging, but don’t worry, you’ll work your way up. You must excuse me. Things are getting out of control.’

Sylvester plays these quieter moments quite beautifully.

Redvers has the whole universe to explore for his catalogue. New horizons, wondrous beasts, light years from Zanzibar

The ending almost evokes ‘The Daemons’ where Jo’s illogical self-sacrifice leads to the destruction of Azal. Here the Doctor’s evocation of change and evolution leads to the apparent ‘suicide’ of Light – the only way that he can ultimately stop change – to give up ‘life’ itself.

LIGHT: No! All slipping away.

DOCTOR: All is change, all is movement. Tell me, Light, haven’t you just changed your location?

LIGHT: Not yet.

DOCTOR: What ‘s the matter, Light, changed your mind?

LIGHT: You are endlessly agitating, unceasingly mischievous. Will you never stop?

DOCTOR: I suppose I could. It would make a change.

LIGHT: Nimrod! I can rely on you. Assist me now.

NIMROD: I’m sorry, sir. My allegiance is to this planet, my birthright.

LIGHT: Argh! Everything is changing. All in flux. Nothing remains the same.

DOCTOR: Even remains change. It’s this planet. It can’t help itself.

LIGHT: I will not change. I’ll wake up soon. No change. Dead.

Beyond that, Redvers and his ladylike companion and his butler and their new pet control (the roles reversed), set out to explore the universe, perhaps an unconscious reflection of the TARDIS crews of old? Then they are off ‘Gone, like a passing thought. As long as their minds don’t wander’.

So, ‘Ghost Light’ is a rather wonderful, odd, misshapen jewel at the end of this old show’s history or at least its first chapter. If not the last transmitted story, it was the last recorded and feels like a last hurrah, heralded as one of the best stories for years in a contemporary review in ‘The independent’. Rich in character, memorable scenes and dialogue and underpinned by an interesting exploration of change and evolution – more of which later. Not without its faults, it is never the less something I feel that the show should be proud of – that in it’s final season it should come up with something that feels completely unique, utterly unlike anything that it had done before or since for that matter.

I can’t stand the confusion in my Mind!’

One subject that comes up in most reviews of ‘Ghost Light’ is confusion. It is fair to say though that ‘Ghost Light’ baffled many on its original transmission. I’ll admit that whilst understanding parts of the story, there are some aspects that passed me by at the time, only to be clarified years later once explained by the writer and script editor. Since 1989, opinion has been divided on the story. Either reviewers are quick to dismiss it as something that they don’t understand or that is an incoherent mess or others claiming that they don’t know what the fuss is about and everything is perfectly clear. As ever I think, the truth is nowhere near as clear as that.

The admittedly unconventional plot of ‘Ghost Light’ isn’t told in a particularly complicated way, for example it unfolds in chronological order. There are however issues with clarity – sometimes with the annunciation of actors (hello Sylvester!), sometimes with the sound mix drowning out dialogue and sometimes with the way in which it has been edited. Add in the bizarre collection of characters, straight from Mervyn Peake and the fact that the writer and script editor appear to have forgotten to explain some key plot points, it starts to feel like a story that has deliberately made obscure in its production.

To my mind, with this type of story, you can either chose to go with it, to be fascinated by it and to revel in not having every aspect of it explained to you, or you can choose not to. That is the nature of taking risks with storytelling. ‘Ghost Light’ ticks so many boxes for me personally, that I chose the former. There is a certain satisfaction to be had with storytelling like this or something like ‘The Prisoner’, striving to understand what it all means, the equivalent of attempting to solve a puzzle and also in enjoying not having everything explained to you. I don’t need to know exactly what Light is – an advanced higher species or an AI or whatever, I don’t need to know why he slept for so many years or how his spaceship comes to be beneath Gabriel Chase. What I do need to know though, is what control is, that seems to me to be pretty fundamental to the story. Now that is implied, rather than stated in the script – once you know that ‘Control’ is a control in an experiment it all makes a lot more sense. The problem is though that control as a word has many meanings.

For me the use of the word ‘control’ in ‘Ghost Light’ makes sense, but only really once it is explained to you! The most notable use of the noun ‘Control’ in a character naming sense is its use as a designation for the head of SIS in John le Carre’s novels, shown by the BBC in the early 1980’s. Someone in control. For a generation growing up with ‘A Bit of Fry and Laurie’, which first aired earlier in the same year as ‘Ghost Light’ (1989), it will forever mean Hugh Laurie turning up at secret service HQ with a cup of tea and greeting Stephen Fry’s Head of Service with a cheery ‘Hello Control!’ In ‘Ghost Light’ of course it is used in the scientific sense of a control in an experiment. A creature that won’t evolve or change even if you give it a copy of the Times every day. You can infer it from the following exchange, but a specific line wouldn’t have gone amiss:

DOCTOR: That’s just it’s shape here on Earth. It’s called Light, and it’s come to survey life here.

ACE: It was crashed out in the stone spaceship in the basement.

DOCTOR: And while it slept, the survey got out of control.

CONTROL: Control is me.

DOCTOR: And the survey is Josiah.

So, to some degree it is there – in the story, but not very well spelled out. Substitute ‘Control is me’ for the admittedly clunky ‘I am the experimental control’ or a brief question from Ace and explanation from The Doctor (the usual route for exposition) and it all becomes clearer.

If there is something that is genuinely confusing at the heart of ‘Ghost Light’, it is why it is set in 1883. This is year is fixed by Inspector MacKenzie being sent to Gabriel Chase in 1881 to investigate the disappearance of Sir George Pritchard and being ‘asleep’ in a cupboard for two years. 1883 is 24 years after the publication of ‘On the Origin of the Species’, 23 years after ‘The Great Debate’ and one year after the death of Charles Darwin. I’m sure there were those who still fiercely debated his work many years later (many still do), but it is hardly as burning a ‘new’ theory as it would have been had the story been set say in 1860. The Reverend Mathews should be referring to Darwin in the past tense. The only reason I can think of the choice of year is to allow it to be 100 years after that a younger Ace burnt down Gabriel Chase. Even that doesn’t make sense to me – it is 6 years before the transmission date of ‘Ghost Light’ – Ace is still depicted as a teenager in this story, albeit one that is starting to grow up, so she would have been very young when she burnt the house down surely? One benefit of the later dating does also allow the Doctor’s references to ‘the Hunting of the Snark’ (1876), Jabberwocky (1871) and Alice (1865, 1871) to be contemporaneous rather than future references. Yes, I’m trying to start a ‘Ghost Light’ dating conundrum!

Lemarck, Wallace, Darwin and Josiah Smith

‘Man has been the same, sir, since he stood in the garden of Eden, and he was never ever a chattering gibbering ape.‘

I covered ‘The Great Debate’ on evolution by natural selection in Oxford in 1860 in my introduction, but what of the treatment of the subject of that debate in ‘Ghost Light’? Well Josiah doesn’t so much evolve through natural selection as transmute or metamorphose in a series of intermediate states – the husks – from insect to reptile to Victorian gentleman. Even in that final state he appears to transform – his skin cracking and flaking away, before emerging from this chrysalis in his final form – ready to meet the Queen Empress – the ultimate Victorian social climber – a proper ‘self-made man’. This would appear closer to evolution as imagined by Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus or closer still to Lemarckian thinking. Lemarck posited that interactions with the environment caused changes in an individual across its lifespan and use or disuse of organs or capabilities enhanced or reduced them in an individual and that these could then be passed onto subsequent generations. So, Josiah the individual acquires the characteristics of a Victorian Gentleman, thankfully we are spared the sight of him trying to pass on these changes. The idea of a ladder of evolution, evolution heading towards greater complexity is also Lemarckian – this is Orthogenesis – evolution with a direction – in this case towards a Victorian gentleman – the ultimate evolutionary endpoint at this juncture in history.

I don’t think that this is by design (used with knowledge of the irony of this term), but rather the story doesn’t actually reflect how Darwinian evolution through natural selection works because it uses shortcuts in its storytelling. It would take a longer work than ‘Ghost Light’ to depict that – we would need to see generations of Josiah’s and the forces that influence the suitability of specific genetic mutations within the population on the ability of individuals to survive and breed to pass on their genetic material – a tall order for 3 x 25 minute episodes! What happens when you compress or shortcut that process into a single generation (1 x Josiah Smith) well it starts to look more like transmutation from one thing to another – the husks as intermediate states in a specific direction. But given all of that, the story works well with its subject, I think. You don’t need to technically understand the mechanism behind Evolution by natural selection to understand this story – any more really than you need to understand how a warp drive or anti-matter or hyperspace work in any number of other stories. The story is more about change and its consequences than the mechanism itself or the forces behind such change. To say that you need to have studied evolutionary theory to understand this story totally misses the point. You just need to know the basics or be willing to learn a little, something that ‘Doctor Who’ has been doing since 1963.

Sympathy for the Angel – or ‘Spare a though for poor old Light’

So, Light is a ‘recording angel’. An angel who records the actions and events of an individual life, just writ large to biosphere level. Light here though feels like he might not be organic, maybe rather an AI or something engineered and sent along with the organic Josiah and Control to survey life on earth. His form obviously changes, he is surprised at his form when he wakens and the Doctor confirms that he changes. Various option where originally proposed for the depiction of Light, before the image of an Angel as depicted in the paintings of William Blake was chosen. My reading is that Light understands the process of evolution and that things change – why have an experimental control that doesn’t change and a creature that evolves otherwise – so evolution is built into the survey method and experimental design. It is more that he can’t cope with the fact that his centuries of surveying the planet has produced a dataset that is no longer relevant, except as a historical record.

LIGHT: I once spent centuries faithfully cataloguing all the species there, every organism from the smallest bacteria to the largest ichthyosaur. But no sooner had I finished than it all started changing. New species, new subspecies, evolution running amok. I had to start amending my entries. Oh, the task is endless.

DOCTOR: That’s life.

You would also think that of all people ‘Doctor Who’ fans would sympathise with Light. Endlessly cataloguing 55 years and counting of TV stories, comic strips, books, audio plays, merchandise – all ever growing and changing. Putting everything in order on shelves – physical or virtual. Working out canon and trying to order something never designed to be ordered or to make any sense. Maybe the Doctor should have introduced Light to UNIT dating? Of any sub-set of fandom that you would think would sympathise with Light, it should be those who have embarked on a marathon, people who have, reading this are on their own attempt at cataloguing and analyzing. The sequential from the start, intended to be comprehensive sort, the sort where you might get as far as ‘Ghost Light’, having waded through recons, audio or animation, only to find that a load of missing episodes have been found. Or you might get through the recons and look ahead, with still 49 years and counting of stories to catch up with. Or maybe you are at the start and trying to work out whether or how to fit in Big Finish or ‘Shada’ or ‘Time Crash’, the minisodes or Torchwood or SJA or ‘K9 and Company’ or god help us ‘Dimensions in Time’. Look around this section – you are Light, don’t you ever feel like setting fire to the whole thing and walking away?

Personally, I also belong to another subset of people that might sometimes have sympathy for Light – people who carry out ecological surveys. Anyone who has carried out even the least complex ecological survey can probably understand Light’s dismay at the ruin of his survey results. You define your study subject and objectives, devise your survey techniques and methodology – random sampling, line transects, quadrats, actual count. If you have experimental hypotheses to test, then you devise your experimental control methods and treatments. You go out into the field – with your quadrats, WeatherWriter, GPS, camera or actual traps, with a pooter or reticle binoculars or bat detector or whatever you need and gather your data on the population you are studying and associated data on any other variables relevant to your study – soil type and pH, altitude, attitude, salinity, sea depth, temperature, visibility, community structure etc. You collect the data you need and tabulate it. And then you try to analyze your findings using descriptive statistics, graphs and diagrammatic representations, GIS mapping, analytical packages (DISTANCE) etc., describe your results, test your hypotheses and draw conclusions.

But all the while through this whole process, the biological subjects of your survey are moving or changing or migrating. Even sessile plants – they bud or flower, they wilt and die – the flower heads are eaten by animals, the grass grows around them obscuring them. Fine if you can complete your survey in one day – but what about when it takes weeks? If like some of the species I survey that is a number of weeks in the Spring when everything changes so rapidly, well good luck. In the cetacean surveying I do, it’s even worse, often most of the subjects of your count are underwater at any given time and they move so fast, you have to estimate group size based on your experience and knowledge – but you might be trying to estimate the count of thousands of dolphins in a super pod, all moving at speed, mostly underwater – maybe even mixed species. And then they vanish – all it takes is one Killer Whale. Some whale species can dive for more than an hour and you might never see them again or you could miss most of the group. In any case, their very presence is extremely patchy in a transect of hundreds of miles across an ocean. So biological surveying and analysis is trying to build a mathematical order or model for analytical purposes around what appears often to be chaos or at least an ever-changing subject and environment – in other words life.

In the middle of a survey, you can literally just despair, lose the plot, get lost in data and question the validity of the data you have gathered, the methodology you have devised and what the data is actually telling you. Sometimes you can realise that your experiment or survey design is fatally flawed or that you have forgotten to capture one vital piece of data required for analytic purposes and you might have to start again – maybe even next year if that is even possible. And that is what I think happens to Light, it isn’t that he doesn’t understand evolution or change – it has just ruined his results while he has slept – his work to date, trying to describe an entire biosphere has been for nothing. His task is enormous and before he finishes, things have changed so quickly (like the Peppered Moth referenced in the script) – species have become extinct (the Great Auk who’s eyes light up in episode one or the Icthyosaurs he mentions), speciation has occurred. Much of the Pleistocene megafauna – Neanderthals, Mammoths, ground sloths, glyptodonts, Cave Bears and Woolly Rhinos, are just scraps of skin and bone, frozen in the tundra or under the North sea and well, his data is no longer valid for the time in which he awakens. It never will be. It is a never-ending task and will only ever be an incomplete snapshot in time. For me though that is one of the joys of ecological surveying and a primary reason for doing it – to observe change. Not always for the good – but that is exactly what the survey is there for – to provide the data to measure population, community, ecosystem and environmental change. So that at least we know when things are changing or degrading as a result of human intervention or poor habitat management. Or alternatively, we can know when things are improving or which experimental treatments work best.

Trust me Light, I’ve been there – and the Doctor can ¤¤¤¤ right off with his slivey toves and bandersnatches, surveying life is difficult enough as it is.

Change and decay in all around I see

Everything changes and all things come to an end. ‘Ghost Light’ was the final story to be made in the original run of the show. It was also the last story made at TV Centre – ‘An Adventure in space and Time’ providing a coda to that particular story. Under BBC management (the equivalent of the Victorian gentlemen of this story) the show was as endangered as the Great Auk or Charles Dodgson’s Dodo – ‘File under Imagination comma lack of’. It was coming to an end, but would change again, returning as the Virgin New Adventures books, or the DWM strip. But the next time these adventures would be picked up on TV it would have evolved into the ‘X-Files’ and would be filmed in Vancouver. In some ways, a story based on evolution, change and extinction would have been an appropriate ending for the show – a show that would return, changed and would continue changing. Marc Platt dodged that bullet and that ‘honour’ instead fell to Rona Munro (up next) – appropriately called ‘Survival‘.