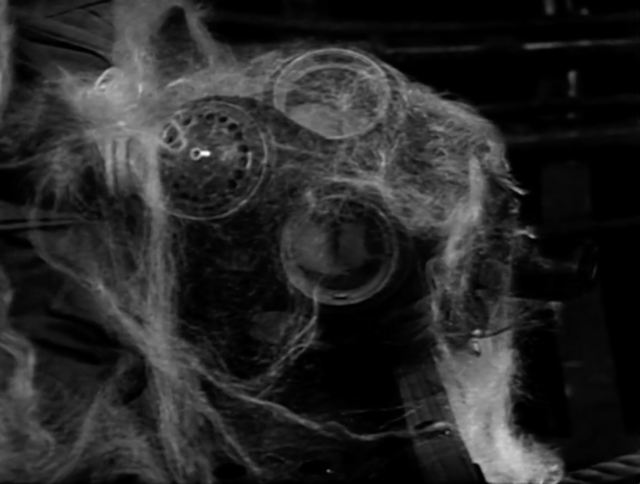

‘The huge, furry monster reared up, as if to strike. Well over seven feet tall, its immensely broad body made it seem squat and lumpy. It had the huge hands of a gorilla, the savage yellow fangs and fierce red eyes of a grizzly bear.’

‘In the empty hall, the Yeti stood motionless, surrounded by devil-masks, mummies, dinosaur bones and all the other oddities of Julius’s collection. Then a faint signal, a kind of electronic bleeping, disturbed the silence. It seemed to come from outside the window. Suddenly the glass shattered, broken by the impact of a silver sphere. It was as if the sphere had been hurled through the window from the street outside. But the silver missile did not drop to the ground. It hovered in mid-air. Then it floated slowly towards the Yeti and disappeared into the still open hollow in the creature’s chest. Immediately the flap dosed over it. Alarmed by the noise of smashing glass, Julius ran into the room. He stopped, seeing the shattered window, the glass on the floor. Was the old fool Travers to insane he was now throwing bricks through the window? Julius looked out. The street below was silent and deserted. Julius decided to telephone the police.

On his way out of the hall, he stopped for another look at his beloved Yeti. He gazed proudly up at it. The Yeti’s eyes opened and glared redly into his own. Appalled Julius took a pace back. The Yeti stepped off its stand, following him. Its features blurred and shimmered before his horrified eyes, becoming even more fierce and wild than before. With a sudden, shattering roar the Yeti smashed down its arm in a savage blow…‘

In the introduction to the two Yeti stories, I wrote about my personal history with ‘Web of Fear’, but I don’t think that the fact that it was my first Target book that swayed my opinion of this story. It is more the case that when I looked at the cover of that book and read the synopsis on the back cover aged 7, I selected something that I knew I would love – it wasn’t made at random, I made the conscious decision that that was exactly the sort of thing I loved in ‘Doctor Who’. It was a very astute choice on my part. Looking at the list of Target books, it must have just been published when I bought it – towards the end of the school holidays. It came down to a straight choice between ‘Web of Fear‘ or ‘The Loch Ness Monster‘ – both of which I love anyway,

So, I approach this with some trepidation, you see ‘Web of Fear’ is quite my favourite story – well I say joint-favourite these days, I can’t find it in myself to separate it from my other true love ‘Ambassadors of Death’. With all that in mind, since it was returned to the archives, I’ve very much been rationing my viewings of ‘Web of Fear’, almost saving it up for a special occasion. Well one hasn’t turned up yet – so it is time to dust it off and watch it again – curtains drawn, reliving that morning, when as a grown man (or at least a very rough approximation of one) I got up early after a long week working away from home and for a few hours was transported to a dark world of Yeti in the underground. Hopefully you’ll forgive me if I also intersperse this with favourite parts of the novelisation?

A horror story for children?

I was struck whilst watching the story again, that for something that I love unreservedly, ‘Web of Fear’ is really quite horrible. It is a horror film made for children, by people who just made it as a horror film and forgot that it was supposed to be for children. From the opening scene in Silverstein’s gothic museum, Bartok playing grimly, candles flickering in the background – it is played as a straight horror film. The Yeti coming to life and then smashing the old man lifeless, as covered in the excerpt from the Terrance Dicks book, is really quite grim. There is nothing in that first episode that couldn’t have been in the opening 20 minutes of a Hammer film. I think the production team must have realised that – they even went so far as to produce a specially filmed trailer with the Doctor warning children that the Yeti where much scarier this time around.

My partner, who has only ever seen Patrick Troughton’s Doctor in ‘The Three Doctors’ asked a few years ago to watch my favourite story, she is a child of the Pertwee era and loves Nick Courtney as the Brigadier and so I put on episode one of this story. Her reaction was interesting – we didn’t get to episode two, she found it too dark and horrific. That brings me to something that I think partly explains why I loved ‘Doctor Who’ as a child – that it was a children’s programme made by adults, with little quarter given to the fact that children formed a core part of its audience. Unlike other children’s programmes, children don’t really feature at all, it is adults doing adult things (no not in that way!) and directed and written by people who would work on anything from ‘Z-Cars’ to ‘The Sweeney’. In short it is wrong and amongst the history of the series from 1963 to 1989, ‘Web of Fear’ is amongst the most wrong and irresponsible. And I absolutely love it.

If the watchwords for ‘Abominable Snowmen’ were ‘cold’ and ‘desolate’, then for ‘Web of Fear’ they would be ‘dark’ and ‘grim’. Dark really in the literal sense that it is almost completely set in the darkness of the underground, almost the exact opposite of the over lit BBC 1980’s productions. Likewise it differs from ‘Abominable Snowmen in that story is virtually silent, except for the whistling of wind blowing across the mountains, here we almost have a sensory overload of music, gunfire, the web guns, explosions, the beeping of yeti control spheres and the horrible, discordant sound made by the web. Only in a very few scenes – mostly those eerie moments in the tunnels in the dark does the sound level drop to just to the sound of echoing footsteps.

‘Grim’ is also a very good term for ‘Web of Fear’, when the light relief is a coward who lets down everyone around him or the opening scene where the TARDIS is trapped in a web in space, you know things are going a bit dark. It pushes the ‘trapped in a confined space, as the people around you are killed one by one’ theme about as far as it can go in a family show. Here’s the thing though ‘dark and grim’ really don’t necessarily make a good story, there are plenty of them in ‘Doctor Who’ that really aren’t very good, but I think what makes this so good is that it is well-written, extremely well cast and directed by what I still think is the best director the show ever had. More than that and this is where it is like ‘Androzani’ is that it is made with utter conviction. Everyone just plays a potentially rather absurd premise as if it is entirely real, which gives the whole situation a proper sense of drama and building tension – if Anne or Professor Travers had died part of the way through this or turned out to be the Intelligence’s puppet, it would not have been all that surprising. So the stakes a very high, the situation desperate and getting worse and it makes the story extremely watchable – even after you know the answer to the ‘who-dunnit’ aspect – the identity of the Intelligence’s agent.

Going underground…

So Yeti, in the London Underground, using web guns, whilst web/foam/fungus spreads through the tunnels, cutting off the survivors and choking those who it engulfs? Everyone it seems realises that this is ludicrous. Yeti – they make sense in Tibet – but in London – with web guns? However when you think about it, it makes sense within the narrative. As in many a Mummy film (or indeed artefacts in many a London museum) – they were brought here from ‘the orient’ by a British explorer and placed in a museum. The ill-advised tinkering of a scientist brings them back to life and provides a pathway for the return of the Intelligence. That is why the trap is set in London – Travers is the vector for bringing this infection to the capital.

The web and mist also makes so much sense in the context of the setting, rather than the protagonists or narrative. The poisonous mist bringing the city to a standstill was familiar to so many British city dwellers in the 60’s. Londoners especially had the great smog of 1952 in living memory – during which thousands are estimated to have died. The Clean Air act was only 10 years old when this aired, coal was still the primary fuel and smog was still a familiar problem, indeed the next story (‘Fury from the Deep’) even deals with the introduction of a new technology (natural gas) to try to resolve the issue. During the great smog the city closed down – with the London Underground the only transport still operating – a shelter from the mist above.

In his marvellous review of ‘Web of Fear’ in DWM (more of this later), Mathew Sweet compares the new, scarier, matted-fur Yeti to the soot-covered rodents of the underground, which you see scurrying between the tracks. I’d go further – the underground tunnels filling with a web-like again, like the mist above ground, also reflects the reality of London. Transport For London employs ‘fluffers’, who are the mostly female underground cleaners who in the dark, at night, with the electricity turned off, clear the tunnels of a build up of fluff – dust and dirt and I imagine maybe the odd cobweb. Without these underground workers, the London Underground would be gripped in a ‘Web of Fear’ and one by one the lights on the tube map would go off…

No review of this story would be complete without praising the sets and quite right too they are superb and very detailed. Never once do you question the location, the darkness and stark black and white images also help to sell this. However there is more to the setting than just the realism of the sets, in some ways the underground itself is a character in this story. The underground and the wartime fortress also explicitly tap into the national psyche. This story was aired just 22 years on from the end of the Second World War and the images of the underground as a haven resonate far beyond just the city itself. During the blitz the underground provided shelter to the population of London and the underground bunkers allowed the government of the war to continue. So it is a traditional place of sanctuary as well as an everyday transport network for Londoners. In fact with much of London above ground covered by the mist, it is also a sanctuary for the military operation in this story. IMathew Sweet notes that after the war, one Henry Lincoln was stationed for a while in Eisenhower’s underground HQ at Goodge Street… Oh and another snippet of information that I found on that, was that those tunnels at Goodge St are now used to store archive film and videotape, you don’t that deep under London somewhere might be episode 3?

So if the underground is a traditional sanctuary ‘Web of Fear’ breaches that. The menace is both above ground and spreading inexorably through the underground in this conflict – the place of sanctuary becomes a trap, as one by one the lights on the tube map go out and the menace creeps ever closer to the Goodge St fortress, encircling the trapped British soldiers in a manner reminiscent of Dunkirk. In that sense and in its depiction of the regular soldiers of the British Army ‘Web of Fear’ is the closest story we have, possibly with the exception of ‘Dalek Invasion of Earth’ to invoking wartime in Britain. In this I would actually include all of those stories actually set during the war, which somehow romanticise the war far more than those 2 stories. I mentioned the ‘whodunnit’ aspect of the story – but really it isn’t that at all – it is a typical wartime story of a mission behind enemy lines with a traitor within, someone who is signalling and aiding the enemy – the agent of the Intelligence is really a fifth columnist and while they are at large the work of Ann, Professor Travers, Knight and Lethbridge-Stewart are doomed to fail. So we have a war film, that is actually a horror film, where the enemy are Yeti, but in fact the menace it is closer to bacteriological warfare and where the traditional sanctuary of the last war has become a trap.

I have my own relationship with the underground. As a child I was fascinated by it every time we visited London. The station names were rather like the names of actors on the credits of others TV shows – I used to spot which ones had been in ‘Doctor Who’, likewise I would spot the names on the tube map from ‘Web of Fear’. I’m once more working and staying in and around London, for the first time since 2005, using the underground most days. My last spell was working in Aldgate, where on the 7th July of that year, I narrowly missed the train which was attacked by terrorists on its way to Liverpool St. As I walked around the corner to the office I worked at, the suicide bomber set off his bomb. 52 people died in a series of explosions across London that day. I spent the rest of the morning in a bomb-strengthened room, trapped inside the police cordon, facing across from the entrance of Aldgate station, where the emergency workers were rescuing survivors and the injured and bringing out the bodies. Despite all of that and the more mundane everyday indignity of being wedged into tube carriage on the way to Kings Cross, thanks to ‘Web of Fear’ the underground still holds a special place in my heart – Goodge St, Covent Garden, Holbourn, Piccadilly Circus, Leicester Square, Tottenham Court Road, Goodge Street and Warren Street …

Her Majesty’s gutter press

Harold Chorley, London Television Journalist, actually. The government, in its infinite wisdom, decided only to allow one correspondent down here. The press chose me.

The use of a reporter as a character to frame a story is very much a device used by Nigel Kneale. Kneale uses James Fullalove, the investigative journalist in the first story to tell one strand of the story and later in Quatermass II, Hugh Conrad (Roger Delgado) investigates the disturbances in Winnerden Flats and finally in ‘Quatermass & The Pit, an American TV reporter covers the flames engulfing London – very much evoking the US coverage of the Blitz. Here though Haisman and Lincoln, use the journalist less as a framing device (he isn’t even used to tell the backstory – we instead get that via the Colonel’s briefing session) or as an investigator – he is more of a decoy. The weight of suspicion for the Intelligence’s agent in the fortress falls on Chorley and he is so odious and self-important that it is a shame the a) he survives and b) isn’t the traitor. It also feels that Chorley is there mainly for the purpose of the authors venting their dislike of the gutter press.

Our man in the Fortress is Harold Chorley – a man who is universally disliked by every person he meets in this story. My favourite thing about Chorley, is that while he is a effectively a war correspondent embedded within a military taskforce – reporting from a surrounded enclave in a war zone, he does all of this wearing a sheepskin coat. A coat that I’ve only ever seen John Motson (football commentator) and Alan Partridge wear! Is that coat Yeti proof – is it BBC combat-issue – was Kate Adie issued with one for the Gulf War or Sierra Leone? Mathew Sweet in his review compares him to Alan Wicker and there is an element of that sort of smarm. You can imagine, like Wicker he would prefer to be hobnobbing with the rich and famous in the south of France, rather than trapped underground in mortal peril. He is so obnoxious that you really can believe that the other members of the press nominated him for the job! This exchange with Anne Travers is typical of the man:

CHORLEY: Oh, for goodness sake, why is everybody being so evasive? Why won’t anybody answer any questions?

ANNE: Perhaps they’re afraid you’ll interpret them in your own inimitable style.

CHORLEY: And what does that mean, pray?

ANNE: It means you have a reputation for distorting the truth. You take reality and you make it into a comic strip. In short, Mister Chorley, you are a sensationaliser.

Lethbridge-Stewart quickly gets the measure of Chorley, plays up to his self-importance and in the process brilliantly sidelines him:

CHORLEY: Look, Colonel, you’ve got to do something. We can’t just stand here waiting, can we?

COLONEL: Ah, Mister Chorley. You’d like to help, wouldn’t you?

CHORLEY: Well, I…

COLONEL: Yes, of course you would. Now look, I’ll tell you what I want you to do. We shall all be rushing about a bit, so what I want you to do is to wait in the Common Room. Act as a sort of Liaison Officer. You could do that, couldn’t you?

CHORLEY: Well, I don’t know, I

COLONEL: Yes, of course you could. Off you go. We’ll all report progress to you personally.

…

COLONEL: Right, that’s enough diplomacy for one day

Chorley is sent to his room to play on his own with some pens and paper! Many decent people die in this story, Chorley isn’t one of them – a trick that has also been pulled in stories as diverse as ‘Voyage of the Damned‘ and ‘Flatline’. It rather neatly reminds us that death is random, often deeply unfair and doesn’t just come to those in a story who you feel deserve it.

The Scientists

Anne Travers is just one of series of pretty decent female roles running through the Troughton era – from Janley through to Lady Jennifer, via Sam Briggs, Miss Garrett, Astrid, Fariah, Megan Jones, Gemma Corwyn, Gia Kelly and Madeleine Issigri. She is also almost a prototype for the character of Liz Shaw, who Derrick Sherwin will introduce in ‘Spearhead from Space’ – a very competent, confident female scientist, who is quite capable of sticking for herself amongst the military men. She works beautifully with Troughton – who does that flirting/bashful thing that he does with Astrid, Gemma Corwyn and Megan Jones – very much tapping into Troughton’s real life. Although Anne is very much able to stick up for herself (see that exchange with Chorley I highlighted earlier), she is a little more vulnerable than Liz, although that has a lot to do with the presence of her Father and the Intelligence taking over his body. It does make me laugh though that despite the desperate situation in a base more under siege than any we’ve so far, she somehow finds time to change and do her hair between episodes – which is almost as impressive as re-programming a Yeti control sphere – she is some woman!

There is this rather nice scene with Captain Knight:

KNIGHT: What’s a girl like you doing in a job like this?

ANNE: Well, when I was a little girl I thought I’d like to be a scientist, so I became a scientist.

KNIGHT: Just like that?

ANNE: Just like that.

He’s just trying it on in a clumsy, cliched way and she puts him down – but more in a kindly way – she’s heard it all before, she saves her real ire for the likes of Chorley who completely deserves it. This scene strikes me as very real – a man who has seen lots of people die, who has been trapped in a confined space, in a desperate situation surrounded by other men, just wanting to spend a few moments with a bright, attractive woman, but making a mess of it and looking like a bit of an arse in the process. It is a lovely performance from Tina Packer, a shame we didn’t get to see her again.

Although softened a bit from his often quite unpleasant character in ‘Abominable Snowmen’, Jack Watling makes Travers eccentric, doddering but also quite fierce. I will cover this in a later post, but I quite like the way that his casting blurs the lines between Victoria and Debbie Watling and their respective fathers. His softer moments are reserved for his scenes with Anne or Victoria. It must run in the family, but like Anne, he really saves the worst of his bluster for Chorley, possibly a hangover from his treatment by the press in the 1930’s. The other obvious factor in play here is that Travers causes all of these deaths through bringing the Yeti and the control sphere to Britain. What exactly was he trying to achieve by trying to re-activate the sphere? His bluster might partially be be a cover for the guilt he feels at bringing all of this on his country and the people surrounding him.

It is also I think fair to say that it isn’t exactly a subtle performance by Jack Wailing. His performance whilst possessed by the Intelligence is over the top, but only registers about 0.3 on the Briers scale – or about a quarter of a Furst or a third of a Crowden. He just about gets away with it – it is very much a classic ‘Doctor Who’, possessed by an evil alien performance – it has a scale to match the small screen, but isn’t exactly naturalistic.

The boys from the Mersey and the Thames and the Tyne

For me, it feels very important in this story, that it is the British Army, rather than a specialist group like UNIT that is left surrounded, demoralised and fighting a rearguard action. The military depicted here is the one familiar from war films from the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s. This is in contrast to the futuristic UNIT force for ‘The Invasion’ – beige, casual uniforms and military transport plane and all. Lethbridge-Stewart might wear a Highland Glengarry cap in this story – but he is also wearing battle dress. The mixture of soldiers from different regiments (Paratroopers, REME, ME etc.) here are most reminiscent of the bomb disposal squad in ‘Quatermass and the Pit’, again working class, technical men.

This is probably the largest group of working class characters in the show up until his point. Even the officer in charge when the story starts – Captain Knight is very much more working class than his later replacements – Captain’s Turner, Munro, Hawkins and Yates. And all the soldiers here (Knight included) spend a lot of time grumbling, groaning and rolling their eyes at the mess they are in and the ‘right Fred Karno’s army’ or ‘a proper holiday camp’ that surrounds them. Now this seems entirely realistic to me – most people who work in a British workplace would recognise the gallows humour on display and the resigned sense of ‘you don’t have to be mad to work here, but it helps..’.

My Dad did his National Service in the Signals – alongside working men (a lot of qualified electricians) from Wales, Scotland, the north of England and London. His best mate was a Glaswegian, a man who could drink whisky like nothing I’d seen before or since – a Scouser and a Glaswegian – always a good combination! I can just imagine the two of them here laying out cabling in the tunnels or wiring in detonators or trying to fix the radios, grumbling away, moaning about the officers. The story rather marvellously pauses for a scene, which always reminds me of them, between two ordinary soldiers chatting over a mug of tea – Corporal Blake and Craftsman Weams. It is one of my favourites in the whole series :

WEAMS: Tibet? Tibet? You’re joking.

BLAKE: That’s where old Travers says they come from. He reckons they’re Abominable Snowmen.

WEAMS: Well, he’s off his chump, ain’t he? How’d they get here in the first place?

BLAKE: Come through the post, don’t they?

WEAMS: Nah, seriously. Outer space, that’s where they come from. Well, that’s what I reckon, anyway.

BLAKE: Oh do leave off. You’ve been reading too many kids’ comics, you have.

WEAMS: All right then, Corp, where do they come from?

BLAKE: It’s a foreign power, ain’t it? Bacteriological warfare, that’s what that stuff is in the tunnels.

WEAMS: What, that fungus stuff?

BLAKE: Yeah. And them Yeti are some sort of new weapon. Well, a sort of robot army.

WEAMS: What, you mean it ain’t real then?

BLAKE: Well of course they ain’t, you nit! Otherwise we’d be able to knock ’em out with the small arms, wouldn’t we?

WEAMS: Yeah. Nothing hardly touches them, does it?

BLAKE: Not unless you can cop ’em straight between the eyes. Then they’ve had it.

WEAMS: Yeah, well that’ll take some doing. I mean, I’d have a job just holding me arm steady if one of them ugly creeps came at me, wouldn’t I?

BLAKE: Yeah. I wish we had some more hand grenades, cos they’re the things that seem to stop them dead in their tracks.

WEAMS: Yeah, but we ain’t got any, have we?

BLAKE: It’s a pity that ammo truck they stopped at Holborn had all the gear in.

WEAMS: Stone me! Here, we ain’t got much of a chance if we come up against that lot, have we.

BLAKE: Not with the funny old crowd we got down here with us. You got civvies, RE’s, REME.

WEAMS: Here, watch it, mate.

BLAKE: The lot. A right old Fred Karno’s Army, innit? Still, not to worry, me old son. Not the end of the world, is it. Want some more tea?

That is a nice, quite long scene, which really doesn’t push the plot along at all, but really gives the piece a nice, realistic feel. It serves to point out the slightly ludicrous aspects of the plot and frame them and bind them in a sort of realism, with the characters reacting in a realistic fashion, even though the circumstances are fantastical – robot beasts from Tibet in the London Underground. It isn’t a scene required by the plot at all, but neither is it filler – it has it’s purpose. I’ve never understood the notion that anything that doesn’t move the plot along should be cut and is unnecessary. Why? From Binro the Heretic, through the tales of Tulloch Moor, through stories of The Icelandic Alliance, most of my favourite parts of ‘Doctor Who’ are just there to provide colour and depth and detail to the world. Why would you want to cut these – it makes no sense at all to me? When that approach his taken to the extreme, you end up with what feels like the edited highlights of a better, richer story.

I will write more about Staff Arnold and the Colonel in later pieces, but the two soldiers who get the most screen time aside from those are Captain Knight and Driver Evans:

Knight is an interesting character. He would originally have been played by Nicholas Courtney – but try as I might, I just cannot imagine this. In fact he is almost created to provide a contrast to Lethbridge-Stewart when he arrives like a breath of fresh air in episode 3. Knight feels like someone who has seen too many people die, who has been beaten down by continual defeat and as a result has become jaded and cynical. His attitude to the Colonel when he appears, verges on insubordination at times, he is wary about the Doctor and his cliched attempts at chatting up Anne aren’t entirely endearing. However, he still manages to be quite a likeable character, just doing his best in difficult circumstances. His death in episode 4, the Doctor messing about in the electronics shop, just long enough for Knight to be murdered, is rather affecting.

And then we come to Driver Evans. I really don’t know what to make of this character, Sometimes we are invited to find him funny or endearing – the light relief in a pretty grim set of episodes, but often he is just a self-centred coward, who lets everyone else down. Before the telesnaps appeared, I’d always imagined him played by Welsh actor Talfryn Thomas, who might have made him a bit more likeable. I’m also not sure if the writing is slightly at odds with the direction – the looks that Jamie, Arnold and especially Lethbridge-Stewart (in the scene where he refuses an order) give him make it clear that this is someone who is a coward and someone that other people are dying for – Lane for example in episode 4. He isn’t anywhere as unpleasant as Chorley, but again, he survives when others lose their life and I can’t say that I entirely like him.

The Life and Death of Colonel Lethbridge

It isn’t often in a TV series that we get see an actor and the character that they play grow from their younger, prime years, through middle age, to retirement and the end of their life in realtime over the course of the best part of 50 years. On British TV this is usually the preserve of the stars of long-running soaps – Ken Barlow in ‘Coronation Street’ springs to mind. This has happened twice in ‘Doctor Who’ beyond the lead character, with characters that whilst not regulars throughout the whole run have re-appeared with a degree of frequency, such that their fans span multiple generations. Before we begin this journey with Alastair Gordon Lethbridge Stewart and Nicholas Courtney – one of the most beloved and enduring characters in the shows history, another character has to die – Colonel Lethbridge as played by David Langton.

It is co-incidental that as with another of the series major characters, whose life we also see unfold over many years – Sarah Jane Smith, there is a near miss where another actor (April Walker) was originally cast. Now Langton is a decent actor, as was the second choice Nicholas Selby, but it is difficult to see how either could have managed to make the sort of impact that Nicholas Courtney did. After both turned down the role, Courtney, who had also been very effective as Bret Vyon, a couple of years before for Camfield, stepped in and effortlessly makes the part his own and in the process becomes almost universally loved, something not easy in the world of fandom. Courtney even became the senior representative of the show during the ‘Wilderness Years’ after Jon Pertwee’s death.

We follow Courtney and the character from this point as a young Colonel, disappearing with the show in season 26, re-appearing via the New Adventures and Big Finish and various fan productions, to his final appearance in the ‘Enemy of the Bane’ episode of the Sarah Jane Adventures in 2008 as the retired Sir Alastair. The character survives even beyond his death – represented in images and words as a heroic figure of myth in a range of stories and also by his daughter, the new head of UNIT. He is a character who the Doctor visits regularly in old age and who’s death in a nursing home is marked in a rather moving scene and who controversially even appears beyond the grave. His last mention is in the last episode transmitted as I write this – we see his Grandfather Archibald Hamish Lethbridge Stewart at Ypres in ‘Twice Upon a Time’ in Christmas 2017 – almost 50 years after ‘Web of Fear’. Having an impact over such a long time period is not an easy thing to achieve and isn’t something that happens often.

Fingers are still crossed for that ‘Web of Fear’ Special Edition containing episode 3, however even if that episode were to re-appear, it wouldn’t show the first meeting between the Doctor and the Colonel, as it happens off camera. So, since we still can’t see the first meeting in the tunnels – here’s what Terrance Dicks has to say about it:

‘The Doctor groped in his pocket, looking to see if his torch had survived unbroken. It hadn’t and he threw it away. Suddenly a light-beam flashed out of the semidarkness and a clipped voice spoke. ‘Stand perfectly still and raise your hands.’ The Doctor obeyed. A tall figure appeared, torch in one hand, revolver in the other, covering the Doctor. It was a man in battledress, the insignia of a Colonel on his shoulders.

Even through the semi-darkness the Doctor caught an impression of an immaculate uniform and a neatly trimmed moustache. The soldier peered down from his superior height at the small, scruffy figure of his captive. ‘And who might you be?’ he asked, sounding more amused than alarmed. Feeling at something of a disadvantage the Doctor answered sulkily, ‘I might ask you the some question.’ ‘I am Colonel Alastair Lethbridge-Stewart,’ said the precise, military voice. ‘How do you do? I am the Doctor.’

‘Are you now? Well then, Doctor whoever-you-are, perhaps you’d like to tell me what you’re doing in these tunnels?’

Although neither of them realised it, this was in its way as historic an encounter as that between Stanley and Doctor Livingstone. Promoted to Brigadier, Lethbridge-Stewart would one day lead the British section of an organization called UNIT (United Nations Intelligence Taskforce), set up to fight alien attacks on the planet Earth. The Doctor, changed in appearance and temporarily exiled to Earth, was to become UNIT’s Scientific Adviser. But that was all in the future. For the moment the two friends-to-be glared at each other in mutual suspicion. ‘Never mind how I got here,’ said the Doctor impatiently. ‘You wouldn’t believe me if I told you. The important thing is that there are Yeti in these tunnels. They’re robot servants of an alien entity called the Great Intelligence. We must warn the Authorities at once.’ Lethbridge-Stewart’s revolver, which he had lowered on seeing the Doctor’s harmless appearance, was raised to cover him once more. ‘The Authorities already know about the Yeti, Doctor. But not, it seems, as much as you do. I think you’d better come with me.’

Dicks is viewing the introduction from the hindsight his own era of the show – although ‘Web of Fear’ was also the story being worked on as he joined as assistant script editor. He knows that the children reading his books will already know the significance of meeting Lethbridge-Stewart and the role he will play in the show in the future – ‘Terror of the Zygons’ had just aired when he was writing the novelisation. It isn’t an indulgence on his part – more that he can’t avoid how important this moment will be – he moves the scene and in doing that removes Victoria from it to concentrate on the meeting of two future friends. The TV version doesn’t have the benefit of hindsight, Lethbridge-Stewart is just another character at the fortress, another soldier who might be the Intelligence’s agent (not that we know there is one at this point in the story) or might just be fodder for battle in episode 4. We don’t even get to see their meeting, what we do get is their meeting with Victoria, presumably very soon after they have met.

Although Haisman and Lincoln created the character of the Colonel and Derrick Sherwin has also tried to claim credit, for my money the real credit for the creation of one of the show’s longest running and most beloved characters belongs to the man who (eventually) cast Nicholas Courtney in the role. Douglas Camfield re-made the character of Colonel Lethbridge in the image of someone he admired (Lt Col. Colin Mitchell) and in the process made him an Anglicised Scot, gave him a double-barrelled name and made him an officer like Mitchell in a Highland regiment (Michell’s was the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders). Take a look at how closely the look of Lethbridge-Stewart resembles Mitchell:

Now Mitchell leading his men into the Crater District in Aden was the last gasp of empire and he later stood as a Tory MP. He was a small, wiry Scot who worked is way up from the rank of Private and neither Nicholas Courtney nor the original casting choices physically resembles him much, in fact someone like Fulton Mackay may have been a closer fit. Nor can I see Lethbridge-Stewart leading his troops into battle against the Autons with 15 pipers playing ‘Scotland the Brave’! Although now I’ve thought of that I’m tempted to write it! Strangely the Highland aspect of Lethbridge Stewart would not be mentioned again until the Camfield directed ‘Terror of the Zygons’, the character’s last regular appearance. So, Camfield rather has just appropriated the image of Mitchell, not especially the character – aside from his oft-quoted ‘leading from the front’ and defining him as as an independent thinking, unconventional soldier. It is worth noting that Mitchell is far from just being the right-wing colonialist he is portrayed as – read his obituary from ‘The Independent’ written by his friend the MP Tam Dalyell, a rather surprising friend at that (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-lt-col-colin-mitchell-1330247.html) – he was right wing, but also fiercely anti-apartheid and spent his last days running a charity to clear landmines in places like Angola and Mozambique – showing that caricaturing people on their politics alone rarely presents the whole truth.

Douglas Camfield was supposedly himself rather right wing, somewhat of an anomaly in the BBC of the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. However he was a bloody good director and much-loved by the people who worked with him. Maybe the show shouldn’t always be made by people with the same views as me, I’m not entirely sure that is healthy. I wouldn’t like to see that conviction tested too far, I can’t imagine a story that provided support for Thatcher or Trump, but certainly at a more abstract level – the level that ‘Doctor Who’ normally operates, when exploring things like pacifism, war, appeasement and resistance, a diversity of views can help, we are talking about big moral issues, with no real answers and opposing views that can be legitimately argued.

The Brigadier provides that platform – he provides a reasonable face (mostly) for military action and for the state, so that when the Doctor rails against his actions – it is not just a caricature of a military idiot that he is dealing with (well mostly not), but rather someone who we instinctively like, who is often acting in a not unreasonable way. This is especially useful later for writers like Malcolm Hulke in exploring the grey areas of the morality of military action. Lethbridge Stewart, whilst proudly British and patriotic, is also an internationalist (see ‘Claws of Axos’ for example), he is a traditionalist, whilst embracing the modern and the new world of alien contact, a stick in the mud and also someone who instinctively believes and trusts in the Doctor and his world. This might to some degree also explain why an ostensibly establishment figure was so beloved of generations of younger left-leaning writers – from Ben Aaronovitch through Paul Cornell, Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat

‘Web of Fear’ is in some ways my favourite portrayal of Lethbridge-Stewart (he is hyphenated at this point) – a clever, astute young officer, someone who can galvanize a dispirited collection of people who have been beaten time and again – a born leader. It is the best of him, he is thoroughly professional, decent man – but despite that, everything goes horribly wrong. His attempts at action, all entirely reasonable and definitely required as the fortress faces imminent extinction – result in nearly all of his men being killed. I will talk about this more in the write-up of episode 4, but with hindsight, knowing and loving the character, it is heartbreaking to see him fail and end up in despair.

Another aspect of his character that I love is how he just makes up his mind to trust the Doctor – he works entirely against the obvious instinct – Knight wouldn’t have made that decision, but he also I think realizes that the Doctor is key to the whole situation and probably the only hope that they have.

‘I’ll leave some men behind, Doctor. You and the Professor will be quite safe here.’

‘Will we? Don’t forget, Colonel, someone here is under the control of the Intelligence. That door didn’t open itself—and someone had to place this model to guide the Yeti’

‘Traitor in the camp, eh? Then we must find him!’

‘How can we? We were moving about all over the place when it happened. Could have been anyone—even you, Colonel’

‘Or you, Doctor?’ They looked at each other for a moment, and then the Colonel smiled. ‘We’ve got to trust someone, Doctor, so we may as well start with each other. I’ll keep an eye on my party, you take care of things here, eh?’

The Doctor nodded, curiously pleased by the Colonel’s trust. Starchy sort of fellow this Colonel, but a man you could rely on. Unaware that this was the beginning of a long friendship, they both hurried out of the room.

This results in him even being prepared to believe that the Doctor has a craft disguised as a police box that can help them evacuate the fortress. Contrast that to the way he is written in ‘The Three Doctors’, disbelieving of the TARDIS and that he has travelled far away from Earth, which is absolute nonsense and completely out of character.

KNIGHT: Well, I’ve heard some stories in my time, but that one really takes

COLONEL: So you don’t believe him?

KNIGHT: No, of course not, sir. The whole idea is screwy. A police box?

COLONEL: Well whether you think it foolish or not, we are going to rescue that craft.

KNIGHT: Oh, but sir. Our job

COLONEL: Captain Knight, the Army has failed to defeat this menace. Now the Doctor thinks he might succeed. Personally, I doubt it. But if we stay here, we’re as good as dead. Therefore I do not intend leaving any escape route unexplored, however screwy you may think it.

KNIGHT: Oh, surely Colonel

COLONEL: Let’s get on with it, shall we, Knight?

KNIGHT: Sir. I suppose you’ve considered that the Doctor might be leading us into a trap?

He arrives a bright, energetic presence, determined to make a difference for the better. The scene where he organises a briefing epitomises this, even grumpy old Travers approves! It also reminds me of the Doctor’s impromptu slideshow in ‘The Daemons’ – maybe the two are more alike than they admit in the Pertwee era:

‘The Doctor sat patiently in the Common Room while Colonel Lethbridge-Stewart lectured them all on the crisis. The Doctor had already picked up most of the information from Travers, but it was interesting to see it all set out in order.Lethbridge-Stewart was very thorough. Using a slideprojector as a visual aid he took them through the entire history of events, starting with the disappearance of Travers’s reactivated sphere, followed by the vanishing of the Yeti in the museum. He covered the first appearances of the mist, followed by the appearance of the Web in the tunnels and finally the arrival of the Yeti. He described the Government’s counter-measures, the setting up of a scientific investigation unit headed by Travers, here in the old war-time Fortress at Goodge Street, with a military unit to protect it.

‘Unfortunately the enemy has counter-attacked in force. The Web has been moving steadily closer despite all our attempts to stop it.’ He pointed to a wall map. ‘Above ground, it covers roughly the area enclosed by the Circle Line. Underground, much of that same area is now invaded by the Web. We are besieged.’ The Colonel tucked his cane back under his arm. ‘So much for the past. Now let’s have some constructive suggestions. Professor Travers?’ Travers obviously didn’t care for the Colonel’s military manner. He muttered rather sulkily, ‘I’ve been working on a method of jamming the Yeti transmissions. My daughter is trying to develop a control unit to switch them off. So far we’ve not had much success. Now the Doctor’s here I hope we’ll do better.’

The Doctor smiled modestly, but said nothing Lethbridge-Stewart passed on, ‘Captain Knight?’

‘We’ve not had much success either, sir. Communications are our main problem. The mist and the Web absorb radio waves a lot of the time, particularly over any distance. The Yeti cut phone lines as soon as they’re laid. We’ve tried blowing tunnels to bold back the Web but they’ve managed to sabotage that too. We’re running low on supplies and explosives, particularly hand-grenades. Whenever a truck tries to get through, the Yeti ambush it. They seem to know what we’re planning to do before we start.’ As he finished his tale of woe, Knight seemed unaware of the implications of his words, but they were not lost on the Doctor. He looked round the faces in the room. Travers and his daughter, Harold Chorley, Colonel Lethbridge-Stewart and Captain Knight, Sergeant Arnold standing rigidly to attention. Had the Intelligence already chosen its agent? It could be anyone in the room—except of course for himself and Victoria.

We need time,’ said the Doctor. ‘Time for Travers and myself to find the solution. If you can blow this tunnel here,’ he pointed to the map, ‘we can seal ourselves off for a bit.’

Lethbridge-Stewart nodded approvingly. ‘Good practical suggestion. Explosives, Captain Knight?’ ‘Just about enough left for the job, sir.’ ‘Excuse me, sir,’ said Sergeant Arnold. ‘Suppose the Yeti smother the charge like they did last time?’ The Doctor looked thoughtful. ‘Have you got anything on wheels? Something that will actually run along the track?’ Knight looked at Arnold, who said, ‘I think there’s a baggage trolley in stores somewhere. We could adjust the wheel-gauge…’ ‘Then it’s simple. Load the explosives on the trolley and attach a timing device. Blow the thing up while it’s still on the move—before the Yeti can use their Web-gun.’

‘Excellent idea,’ agreed the Colonel even more enthusiastically.

‘Splendid,’ said the Doctor. ‘Captain Knight. if you and the Sergeant will see to the trolley, the Professor and I will rig up a detonator for you.’

This scene is quite an artful info dump of the history of the emergency we have arrived in the middle of, but it also leads into a plan for the way forward, Lethbridge-Stewart marshalling his resources, he and the Doctor already making a difference and in the process it has also introduced the concept of a traitor in they camp. It really is an artful piece of writing.

If he hadn’t returned in ‘The Invasion’, the Colonel would still have been a great one-off character and this would have been his final scene:

COLONEL: Do you mean to say that Arnold wasn’t the Intelligence?

DOCTOR: No. He was just a poor soldier that was taken over. He was probably one of the first to disappear.

EVANS: You mean it might come back?

DOCTOR: Well, it’s still around, isn’t it? I’ve failed.

TRAVERS: Nonsense, man.

ANNE: You were marvellous.

COLONEL: Yes. Great victory.

If UNIT had started without the Lethbridge-Stewart and Nicholas Courtney, with someone else playing the role of the Brigadier, I can’t help thinking that I would be wondering at this point why they hadn’t just re-used him. I will be returning at various points to the Brigadier and his life across this thread, but in case I don’t get to say it elsewhere – Nicholas Courtney is simply superb, he doesn’t get to do his wryly amused, raised-eyebrow acting in this story, things are far too grim for that, but he does effortlessly build a likeable character – a hero in his own right and in his own way, but one who successfully manages to be that without detracting from the role of the Doctor – to my mind one of the reasons why the character is so enduring. He was one of my heroes growing up, a joy to meet and he is much missed.

The Battle of Covent Garden – Everybody Dies

Episode 4 of ‘Web Of Fear‘ is quite my favourite individual episode of classic Who. It is an absolute tour-de-force from Douglas Camfield, Alastair Lethbridge-Stewart’s darkest hour and for me the most gut-wrenching and tense single episode since ‘The Destruction of Time‘.

In terms of the excellence of individual episodes, there are different criteria you could apply – the opening episodes of ‘Space Museum‘ and ‘Mind Robber‘ or episode 3 of ‘Deadly Assassin‘ – for example are distinctive and interesting and often surreal and any would be a good choice. There are also an array of different, great first episodes (Wheel in Space excepted!), where our heroes explore a new world and meet a new cast of characters. The creepy, horrific first episode of this story is also very high up on my list of personal favourites and I could easily have written a whole piece just on that (probably with the title ‘Londoners Flee! Menace Spreads!). For me, though the episodes that I really love have a velocity, a tension and a sense of conviction that the stakes are high and that anything could happen to any of the cast. For me, this means episode 4 here and the likes of ‘Destruction of Time‘ or ‘Caves of Androzani 3′ and recently ‘World Enough and Time’. Rather like ‘The Destruction of Time’, by the end of this episode you are completely drained, it never lets up. I don’t think that there would quite be another episode like it until ‘Caves of Androzani’, more than 15 years later, it is no coincidence that that was directed by Graeme Harper, who learnt his trade from Douglas Camfield.

The episode starts with the situation around the fortress becoming increasingly desperate. Travers has been kidnapped, Weams and some of the other men are dead, smothered by web and the Colonel still trying to galvanise his surviving men and coming up with a new plan, each time the old one is thwarted.

ARNOLD: What is it, sir?

COLONEL: Something up ahead. It’s all right. Captain Knight and his party.

ARNOLD: They’ve been very quick, sir.

COLONEL: Any luck?

KNIGHT: Afraid not, sir. The fungus beat us to it. A hundred yards this side of Holborn.

ARNOLD: Just as if it knew what we were up to, sir.

COLONEL: Yes.

KNIGHT: There’s just a chance, Colonel, that we might be able to get to Holborn via Piccadilly.

COLONEL: Fungus on the Central Line only, eh?

KNIGHT: Well, it’s worth a try, sir.

COLONEL: Yes, right. Tottenham Court Road, down to Leicester Square, and up past Covent Garden. Come on, follow me.

It also becomes clear that there is a traitor in the camp and that the Intelligence has specifically brought the Doctor to this place:

COLONEL: Doctor. Been thinking about what you were saying earlier. About someone here in HQ being responsible for all this. Could it have been Travers?

DOCTOR: I doubt it.

KNIGHT: Well, after all he has disappeared.

DOCTOR: Yes. So has Chorley. I’d say he was a much more likely suspect.

COLONEL: True.

DOCTOR: On the other hand, of course, whoever is in league with the Intelligence could still be amongst us here.

COLONEL: That’s a fact of which I am uncomfortably aware. But tell me, Doctor, this Intelligence, exactly what is it?

DOCTOR: Well, I wish I could give you a precise answer. Perhaps the best way to describe it is a sort of formless, shapeless thing floating about in space like a cloud of mist, only with a mind and will.

COLONEL: What’s it after? What’s it want?

DOCTOR: I wish I knew. The only thing I know for sure is that it brought me here.

As their options are cut off one by one by the Intelligence, they embark on increasingly desperate measures:

COLONEL: So my party will get above ground and approach Covent Garden by Neal Street. Is that clear?

ALL: Yes, sir.

COLONEL: Now Staff here will be taking the trolley through the tunnel, and will arrive, we hope, at the same time as we do. You picked your two men, Staff?

ARNOLD: Yes, sir. Lane and Evans.

COLONEL: Right. Now as soon as we get there, we shall be looking for a police box.

BLAKE: A police box, sir?

COLONEL: Yes, a police box. Now I want that box either out of the station or onto the trolley as quickly as possible. Is that understood?

ARNOLD: Yes, sir.

COLONEL: Right. Any questions?

BLAKE: Yes, sir, this police box. Is it important?

COLONEL: Corporal Blake, we’d hardly be going to this trouble if it weren’t.

One party has to risk travelling overground, while the other tries to go through the web to try to get to the TARDIS in Covent Garden. Arnold and Lane, protected only be army issue respirators try to push a rail trolley through to the TARDIS:

ARNOLD: The Colonel will be through there at Covent Garden in a few minutes, right?

EVANS: Do you think they’ll be able to load the police box on here, Staff?

ARNOLD: Well, if we can get this thing through the fungus stuff. There’s not much of a gradient in this section of the tunnel. Right, I want one volunteer.

EVANS: Volunteer? That’s a dirty word, that is. Not me.

Later:

EVANS: Staff? Staff Arnold?

Later(Lane is dead, covered in web, Arnold missing.)

EVANS: Staff?

That is a really horrible scene, Lane’s cobweb covered body, pulled back out of the web, Arnold missing presumed dead, before Evans scarpers. To be fair to Evans, he does at least stick around to pull the trolley back and if I learnt one thing from my Dad about his time in the army it was never volunteer for anything

The centrepiece of the episode of course is the battle of Coven Garden as Lethbridge-Stewart and his men are surrounded by Yeti on all sides with the ammunition running low. Terrance Dicks describes this as:

‘Colonel Lethbridge-Stewart and his men were fighting for their lives. As soon as they’d reached the surface, Yeti had appeared to ambush them, tracking them through the misty streets, anticipating their every move. Now the soldiers had taken refuge in a warehouse yard, and still the Yeti were closing in from all sides. Many of them carried Web-guns. The Colonel threw a grenade, and saw a Yeti stagger back from the blast. He reached for another but the bag was empty. At his side, Corporal Blake yelled, ‘I’m out too, sir, so are most of the lads.’ Lethbridge-Stewart realised that with the grenades gone their position was hopeless. No other weapons seemed even to delay the Yeti, let alone stop them. He stood up, cupping his hands, ‘All right, men, scatter and run for it. Don’t bunch up, take different directions. Now, go!’

The Colonel himself sprinted for the warehouse wall, running, dodging men all around. Some were smashed to the ground by Yeti, or smothered by the Web-guns, but others seemed to be getting through. The Colonel became aware of Blake close to him. ‘Run clear, man,’ he yelled. Two men together made an obvious target. But the warning was too late. Blake crumpled, choked by the stifling blast of a Webgun. Dodging a slashing blow from a Yeti, Lethbridge-Stewart jumped for the top of the wall and swung himself over. He dropped to his feet in the street out-side and began sprinting for the Goodge Street tube entrance. He was determined to get back to the Fortress, to see things through to the end’.

Tense as that is, it doesn’t quite do justice to what Camfield gives us. It mixes the ludicrous – the massed Yeti in broad daylight on the streets, with scenes that are also played with utter conviction. Camfield brilliantly gets the most out of this sequences, artfully disguising the Yeti on the streets in a series of crash zooms or shooting them from below. The sequences in the warehouse yard are some of the most tense and dynamic in the show’s history. The troops surrounded on all sides, running out of ammunition and being picked off one by one. By the end of it, most of the men from the fortress are dead, including Corporal Blake, either smothered by the web (a really grim death) or smashed by the Yeti, which despite looking rather cuddly are built up to be really powerful here. Minutes later Knight is also dead, killed while waiting for the Doctor to pick out electronic spares and Lethbridge Stewart is left with Anne and Evans as his surviving force.

In the aftermath, we have this scene, with the Colonel in a state of despair that we will never see from Lethbridge-Stewart again. He knows that his plan has contributed to their deaths and he has achieved nothing – but also I suspect he knows that he had to do something otherwise they would have died anyway trapped in the fortress. By the end of the scene he also knows that it was the yeti model secreted in his pocket that guided the Yeti to their target.

DOCTOR: Colonel!

VICTORIA: Are you all right?

JAMIE: What’s happened?

DOCTOR: Colonel, what happened?

COLONEL: Gone.

VICTORIA: Not all of them?

DOCTOR: All of them!

COLONEL: I said so, didn’t I? All of them. Evans, what about your party? Arnold?

EVANS: Gone, sir.

JAMIE: Captain Knight, too.

COLONEL: Knight. Hopeless.

COLONEL: Can’t fight them. It seems indestructible. Can’t fight them! You were right, Doctor, when you said they were formless, shapeless. You were right.

Compare Lethbridge-Stewart by the end of this episode, to the young, energetic officer who addressed his team at the briefing session in episode 3, he has been broken by one episode of the story. What an episode though.

Douglas Camfield, kick arse action director

Just as there are some great writers in the original run of the show, but for me Robert Holmes is the best by some margin, his directing equivalent is Douglas Camfield. He is the best director of the original run of the show, for me only Graeme Harper comes close. Harper describes his mentor as a ‘kick-arse action director‘, but someone you could also give ‘Romeo and Juliet’ to direct and he would produce a sensitive piece of work. He manages to give his work a filmic quality, even in his early stories despite the cramped, primitive studio conditions and equipment. His location work and action sequences here and in ‘The Invasion‘ are a cut above even the better of his contemporaries (Michael Ferguson for example).

One of the things I really like about Camfield’s productions is the framing of his shots. There is one in particular that he uses a lot, the Doctor in the foreground facing the camera, with the rest of the cast behind him, also facing this way. This might not work for other shows, but is perfect for the Doctor – he is musing in a slightly distracted way in the foreground with the others hanging on his words. Compare these shots from ‘Web of Fear’ and ‘Terror of the Zygons‘, nearly 10 years apart:

In this story Camfield dials up the horror in the first episode, a dark, tense, nightmarish 25 minutes – the sequence with the newspaper seller’s corpse and the death of Silverstein to the strains of Bartok. In later episodes (2 and 4 especially) the action sequences are beautifully shot and he injects pace and intensity into these episodes that most other directors of the classic era of the show could only dream of. In between he employs a range of techniques to keep things interesting including shooting sequences through the web and this rather wonderful shot of Troughton:

He is also rather adept at casting – the ensemble here is excellent, as it is in all of his stories. Just list them – ‘The Crusades’, ‘Time Meddler’, ‘Dalek’s Master Plan’, ‘The Invasion’, ‘Inferno’, ‘Terror of Zygons‘ and ‘Seeds of Doom’– that is a really strong run of stories. It is such a shame that he was taken ill on ‘Inferno‘ and speaking selfishly that we have a long gap between ‘Inferno‘ and ‘Zygons‘ – just imagine what he could have done with some of the stories in between – ‘The Three Doctors‘ or ‘Frontier in Space‘ spring to mind where his direction would have made a huge difference. His wife, Sheila Dunn apparently made him promise to give up directing ‘Doctor Who’ after ‘Seeds of Doom‘ due to the strain it placed him under. Given what happened next, sad though it is, that seems like a fair request.

I will be covering a few of his stories and I’m sure I’ll write some more about his work then. We lost Douglas Camfield far too young, he was only 52. I was lucky to see him interviewed once at a convention in 1982, but I didn’t really know too much about his contribution to the show at the time and so unfortunately it was slightly lost on me, 2 years later he was dead and the show lost one of it’s greatest contributors.

The possession of Staff Sergeant Arnold

I’ve known since 1976 that Staff Arnold was the agent of the Intelligence. However, I don’t think that much is lost by knowing this and the reveal is still terribly sad each time I watch this story. Arnold is one of the story’s most likeable characters. Mathew Sweet notes that he would have been recognisable to many of the Dads watching as a ‘tough, warm-hearted career soldier who made Malaya or Korea bearable with a considerate word or a chit to visit the MO‘ – who in in another timeline might even have been played by William Hartnell. Sweet also reveals some fascinating details about Jack Woolgar (who had also been brilliant as the ex-miner Dad in Dennis Potter’s ‘Stand up Nigel Barton‘) – his distinctive voice was through a chest condition that he had since his youth, but most bizarrely he had apparently been a gigolo in Lucerne, Switzerland between the wars! He is terrific in ‘Web of Fear‘, by turns fierce NCO and good-natured protective father-figure to the young troops.

There is a disparity between how the reveal and death of Staff Arnold are handled in the TV version and in Terrance Dicks’ book:

CHORLEY: It isn’t me. It isn’t me. Don’t you understand? I’m not the Intelligence. The Intelligence is him!

TRAVERS: It can’t be!

ANNE: Oh, it’s too horrible. I don’t believe it!

ANNE: Arnold.

ARNOLD: No, merely Arnold’s lifeless body in which I have concealed myself. But let us to work. There will be time for discussion later. In fact, all the time in the world.

ANNE: You mean, all we’ve done is cut off its contact with Earth? It’s still out there in space somewhere, flying around?

DOCTOR: Precisely! Look.

(at Arnold’s charred, blackened corpse)

VICTORIA: Oh!

CHORLEY: Oh, poor fellow!

COLONEL: Do you mean to say that Arnold wasn’t the Intelligence?

DOCTOR: No. He was just a poor soldier that was taken over. He was probably one of the first to disappear.

In fact in the earliest scripts Arnold was a commissionaire at the Natural History Museum, where the Yeti from ‘Abominable Snowman‘ was an exhibit. As the Yeti transforms in the opening scene, Arnold is in the shadows and encounters the Intelligence. It isn’t clear if Arnold’s body has been lifeless throughout the story or whether Arnold is still in there until this point. It can only really work that way – Arnold functions perfectly as the father-figure Staff Sergeant throughout these 6 episodes something of him most exist and be accessible to the Intelligence. Arnold might not be as mentally strong and able to resist the Intelligence’s control as Padmasambhava, but surely like the Tibetan Master, the Intelligence must share Arnold’s mind?

In contrast Terrance changes this to make this clearer:

Harold Chorley stumbled into the concourse, a Yeti behind him. You said Travers angrily. You were the one who betrayed us to the Intelligence: Chorley was babbling with fear. No, it’s not me, I wasn’t helping the Intelligence. It was him!

From the entrance behind Chorley a stiff figure walked forward, its face an impassive mask. It was Sergeant Arnold.

Colonel Lethbridge-Stewart listened in shocked disbelief as the icy voice of the Intelligence came from the rugged old soldier who had served him loyally. I chose to use the body of Sergeant Arnold from the first, just as I briefly used Travers. He revealed your plans to me, he concealed my Yeti in your Fortress. Now it is time to begin. This is the start of my conquest. And here is the last member of my party.

Jamie came forward, a Yeti behind him as guard. From Arnold’s lips the voice of the Intelligence ordered, Stand by the Doctor.

And his death:

The Doctor turned over Arnold’s body which as lying face down. The features had crumpled into a horrifying deathmask.

The Doctor sighed. Poor fellow.

The Colonel stood beside him, looking down at the body. I just don’t understand. Sergeant Arnold was so brave, so loyal. He took such risks to help us.

When the Intelligence wasn’t in control, Arnold was his normal self, explained the Doctor. Unfortunately the Intelligence could take over his mind and guide his actions whenever it wanted. Afterwards, Arnold had no recollection of what he’d been doing. I suspected it was him when I heard he’d come through the Web unharmed.

The visuals around his demise – the Yeti strangling Arnold as he drops to the floor, his face horribly blackened are really strong stuff. Such a sad ending for such a beautifully realised character. Jack Woolgar plays the possessed Arnold beautifully, his soft, Northern burr, replaced by the icy, RP tones of the Intelligence.

Overall, across the story the themes of possession and the body horror of Arnold’s demise are somewhat over-shadowed by the action sequences and the significance of the introduction of Lethbridge-Stewart, but by the end of the final episode we are left to ponder all that Arnold as been through – a good, decent man used as a puppet by a cruel, alien entity, betraying and causing the deaths of the men in his charge who trusted and relied on him.

Prepare for a great darkness to cloud your mind

At the end of the story we learn that all of this has been arranged for the Doctor’s benefit – to drain his mind for the benefit of the Intelligence. The machine that drains or controls or shows the images imprinted on peoples minds is a recurring theme throughout classic ‘Doctor Who’. It normally resembles an old fashioned ladies hair dryer or as here a colander with some wires attached. We get variations of this in stories from ‘Dalek Invasion of Earth, Mind Robber, Mind of Evil, Day of the Daleks’, Green Death, Planet of the Spiders, Ark in Space, Genesis of the Daleks, Shada and the infamous Mind Probe! Probably many more. I’m not sure where that obsession comes from – possibly it relates to the 1960’s brainwashing of US and British POWs in the Korean War or the experiments conducted by the CIA into remote viewing and other psychic phenomena? Whatever, it won’t be the last time that we see this as a plot element.

At the end of the story, the survivors from Goodge St are all rounded up by the Yeti and Arnold, utterly defeated. It all then goes slightly Vichy government, a whiff of appeasement in the air. There are some especially uncomfortable moments when Lethbridge-Stewart has to talk to the Doctor about the possibility of giving himself up to the Intelligence for the good of Anne and Victoria. It is echoed in later stories when the Brigadier sometimes has to ask the Doctor uncomfortable questions. Mawdryn Undead – his return to the series springs to mind – where the Brigadier has to ask the Doctor whether he will give up his regenerations for Tegan and Nyssa to be ‘cured’, often he is the only one who can do this:

BRIGADIER: Doctor, have you got any ideas? (silence) You said in the laboratory that the Doctor could help you through that machinery.

MAWDRYN: That is true, but only of his own free will.

BRIGADIER: Well then, surely he can do the same for Nyssa and Tegan.

MAWDRYN: That is a question you must ask the Doctor.

BRIGADIER: Well, Doctor?

Even though he has a plan, it seems that even the Doctor has given this some consideration.

EVANS: Permission to speak, sir.

COLONEL: Yes, what is it, Evans?

EVANS: Well, stop me if I’ve got it wrong, sir, but if this Intelligence thing here gets the Doctor, will he leave us all alone?

COLONEL: Yes, that’s what it looks like. What’s in your mind?

EVANS: Well, sir, why don’t we just let it have him? Then we could all go home.

COLONEL: Will this Intelligence keep its word, do you think?

JAMIE: Well, it didn’t in Tibet.

DOCTOR: Jamie.

EVANS: Leastways, it’s a chance.

JAMIE: But it’s not you that’s taking the risk, is it?

EVANS: I reckon he ought to give himself up now.

COLONEL: Evans, when I want your opinion I’ll ask for it.

COLONEL: Been thinking. The Yeti haven’t noticed McCrimmon’s disappearance yet. Not that I think he’ll be able to achieve anything.

DOCTOR: Well, go on.

COLONEL: Well, I don’t really know how to say this, but there’s Miss Travers and Victoria to think of, and, er

DOCTOR: You mean, am I going to give myself up?

COLONEL: Yes. Of course, the decision must be yours, yours alone. But the Intelligence did promise to release Travers and Victoria.

DOCTOR: You believe that?

COLONEL: Well, why not?

There is a lovely moment of humour as the Doctor talks to Jamie and Victoria – telling him that they will have to look after him until he grows up as he will have the mental age of a child. The look on Jamie’s face is priceless!

DOCTOR: It’s all right, Evans. If I don’t come up with the answer, I will give myself up, I promise.

EVANS: That’s okay then.

JAMIE: You will not give yourself up.

DOCTOR: Don’t be foolish, Jamie!

JAMIE: But Victoria!

DOCTOR: She will be your responsibility. And when it’s all over, you’ll just both have to look after me, that’s all.

JAMIE: Ay?

DOCTOR: Well, if what the Intelligence says is true, my mind will be like that of a child. You’ll have to look after me until I grow up.

JAMIE: Oh.

DOCTOR: Don’t worry. I’m going to try not to let it happen.

The ending of this story is quite frequently criticised by reviewers, but I rather love it. The Doctor has a plan, but doesn’t tell anyone else – probably correctly given that the Intelligence can seemingly take over anyone at will. It doesn’t quite work because his friends are so resourceful and save him. Typically, it takes the flattery of Anne (‘you were a hero‘) to melt the Doctor’s anger at his failure to completely defeat the Intelligence – he looks at her rather bashfully and suddenly brightens up. A nice little bit of male vanity, that re-appears in other stories – ‘The Invasion‘ for example where he starts to fix his hair when he sees Isobel photographing him!

Some thoughts on the Intelligence and the Yeti

Across the reviews, I have talked a little bit about the possession of Padmassambhava and Arnold – and the temporary occupation of the minds of Victoria and Travers. I haven’t really talked about the nature of the Intelligence. It is a dispossessed entity, roaming space – perhaps in Victoria (and the Doctor, Travers and Padmassambhava to some extent) it finds a kindred spirit of sorts. Go with me on this one – the Doctor is a temporary father substitute for Victoria, her father died saving the Doctor’s life, her mother was already dead. This Doctor and Jamie however aren’t the most reliable of families and the strain of this mounts up over time. In the next story she will leave to try to find some stability in her life – with another set of substitute parents – the Harris family who she barely knows.

This is picked up on later by Marc Platt in ‘Downtime’, her longing for her father and mother and ‘home’. The Intelligence similarly is wandering without an abode, alone – it wants existence – to be fixed to one place. In ‘Abominable Snowmen’ to the mountain above Detsen, in ‘Web of Fear’ London and especially the network of the underground. Finally in ‘Downtime’ the network of the world wide web – something quite new at that point in time – a world of silicon and copper. Perhaps it also finds this through occupying the minds of its victims? I’ll return to cover some of this at some point in the future, but the Intelligence, despite being ‘evil’ and causing death on grand scale is also rather pitiable – it feels more like something that has lost it’s way, rather than the ‘evil from the dawn of time’ of something like Fenric.

The Yeti are also an interesting foe – a mixture of the cuddly and the hugely powerful and savage. They also have that aspect that the Autons have, possibly even the Weeping Angels. They are inanimate or still at times – the characters are often unsure whether they are on, switched off or just waiting to burst back into life. Some of the scenes are reminiscent of Autons coming to life behind Ransome in ‘Spearhead from Space’ or even of the Weeping Angels, statues moving in the background. Despite not talking – like the Autons (mostly – that scene in ‘Terror the Autons’ just feels wrong) or the Weeping Angels (Angel Bob aside), like both of them they have a recognisable sound. One which means that they work fine on audio – the way that I have experienced ‘Web of Fear’ and ‘Abominable Snowmen’ most often. You have the famous lavatory flush roar – but also the incessant beeping sound (reminiscent of Sputnik) that accompanies them when they are activated. The silence and those moments of stillness, create an uncertainty in the viewer as to what will happen next – a tension that we are never quite sure whether they will react or not. This adds to the creepiness of these stories and in combination with the strength and ferocity displayed by the Yeti – particularly in ‘Web of Fear‘, works very well in ‘Doctor Who’.

Final Thoughts

So there we have it, my favourite story – tense, pacy, horrific, nightmarish – beautifully written, played and directed. A cross between two genres – war films and horror films, but still very ‘Doctor Who’ in the mixture of the slightly ludicrous being played completely for real. It is also possibly more ‘black and white’ than any other story – just look at the selection of images in this set of posts – and the sheer darkness of it all. Unlike ‘The Invasion’, which I can imagine on glorious ITC colour film, ‘Web of Fear’ suits its medium perfectly – it is of the black and white era completely and embraces its darkness.

It is also one the main reasons why I write these reviews. Before that long car journey in 1976, I’d always loved ‘Doctor Who’, after I’d read ‘Doctor Who and the Web of Fear’ by Terrance Dicks, I was a fan. I still am more than 40 years on. That is a testimony to everyone involved – I don’t know whether that is a good thing (it’s given me a lot of happy times) or not (it’s cost me a hell of a lot of money!). I would also like to say thanks again to Phil Morris and everyone who worked on the recovery and restoration of the story – it has given me a great deal of happiness.

Anyway, in that spirit, I’ll leave the closing words to Terrance Dicks:

‘Victoria felt she couldn’t take any more excitement. ‘Oh no, Doctor, what’s the matter now?’

‘Well, as soon as they can they’ll get the Underground running again. Just think we might get run over by a Tube train! And after all we’ve been through, that would be most undignified!’ The Doctor hurried up to the TARDIS and opened the door. Jamie and Victoria looked after him.

‘He’s mad,’ said Jamie indignantly. ‘Mad, I tell you. No telling where he’ll land as up next.’

Victoria smiled. ‘Come on, Jamie, time to go!’ They followed the Doctor into the TARDIS. The door closed and after a moment a strange wheezing, groaning sound filled the tunnel. Slowly the TARDIS faded away.

The Doctor and his two companions were ready to begin their next adventure.’