The Shock of the new? Change and Spearhead from Space

It is easy to assume that ‘Spearhead from Space’ came as a huge shock to existing viewers of the show in January 1970. It also fits perfectly into a narrative when writing about ‘Doctor Who’ in a marathon context, since the change of Doctor, format and the move into colour coincides perfectly with the end of the 60’s and the very beginning of the 1970’s. Even then it’s just too perfect in that it is just the 3rd of January, 3 days into the 70’s when ‘Spearhead’ airs.

It’s too perfect, too neat though isn’t it? I get a bit suspicious when things line up too perfectly like that. Is it just an assumption that is easy to make and rarely challenged? I mean watch ‘The War Games’ back to back with ‘Spearhead’, which I’ve done many times and the changes are huge snd quite startling. Even from the start, a new title sequence in bright primary bursts onto the screen – screaming we are all new and in colour now! This is the first time the titles had changed with a new Doctor as well – Troughton’s new sequence didn’t debut until ‘The Macra Terror’. We have a very different Doctor and ostensibly ‘assistant’ as well and a format based around a team – UNIT and Earth-bound stories. However, whilst it is an entirely valid point of view from a certain perspective (i.e. viewing it today in a marathon type context), it isn’t quite so clear cut when you look at things from the perspective of a viewer in January 1970. I thought that might be interesting to explore a bit further.

1969 and all that

One of the main things that I often see with regard to ‘Spearhead from Space’ is that it is the moment that the show bursts into the 1970’s in colour. Of course, that is true, it was made in colour, broadcast in colour and first broadcast in early 1970. So, all of those things are true. At the same time, it really isn’t quite the case. It aired in January 1970, that is true. However, it was written and shot in 1969 for a start – on location in September 1969 and in studio in October of that year. It is shot on film and in colour, true. However, cleaned up in all its pristine glory, it looks more like a Steed & Mrs Peel era Avengers episode, which aired in 1967. And of course, virtually no one watched it in colour at the time. In fact, if you want to see it the way most people experienced it in early January 1970, then eschew the frankly astonishing Blu-ray version and watch the old VHS, with the colour turned down. If you do that, well it looks rather like its’ season 6 sister production from 1968 ‘The Invasion’. There are also a number of other similarities to that production – the location for the battle sequences, Nicholas Courtney, the UNIT uniforms, the invasion sequences in the city streets and some of the shooting style in particular.

If ‘Spearhead’ has become shorthand for ‘it’ s the 1970’s now’ it is similar in the way that The Beatles splitting up marked the end of the 1960’s. Well, it does in one way – they last recorded together in August 1969. It wasn’t until McCartney announced he was leaving in April 1970 that it was publicly recognized. The legal process went on until 1974. ‘Let it Be’ was released in May 1970. It was still a product of the 60’s though. ‘Spearhead from Space’ straddles the two decades in a similar way to ITC productions like ‘Departments S’ or ‘Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased)’ – which feel both end of 60’s and early 70’s simultaneously. I will talk separately about the influences on this story, but they are largely from the 1950’s, with a splash of late 60’s ITC action. I could probably just about sustain an argument that 1970’s ‘Doctor Who’ proper starts with the sequel to this story – ‘Terror of the Autons’, the full early 70’s UNIT lineup, the Barry Letts primary colours and overuse of the miracle that was CSO. As usual it isn’t black and white, rather a transition, albeit one that looks rather startling at first glance.

A Question of colour

So, we now watch the story in all its restored, DVD or Blu-ray glory, but how many people did originally watch ‘Spearhead from Space’ in colour? In 1969 in the UK, 99,419 colour TV licences were issued (as opposed to 15,396,642 black & white) – in other words something like 99.34% of the potential audience watched in black and white. There are increasingly more colour TV viewers across 1970 as a whole (not that that this impacts the January audience figures of ‘Spearhead’ unduly) – 273,397, still 98.28% of the potential audience watching in black and white. To put that in perspective, a massive 2.2million households (i.e. 10 times as many as colour TV licence holders) still had a radio only licence. Colour TV licences only overtook black and white in 1977. It would be another 2 years after that until we had colour TV in my home, 9 years after ‘Spearhead’ aired. So, the answer is very, very few.

As a matter of interest, BBC2 broadcast its first colour pictures from Wimbledon in 1967. By mid 1968, nearly every BBC2 programme was in colour. BBC1 started to broadcast in colour 1969. So colour isn’t even a 1970’s thing in Britain with regard to programmes being made and transmitted in colour, rather that it’s uptake by viewers increases hugely as the 70’s progresses. It is also just the case that the first ‘Doctor Who’ TV story broadcast in colour was January 1970. Which is ‘a thing’ in its own right – after all, one of the main selling points of the 60’s Peter Cushing films was the Daleks in colour.

The colour TV licence was more expensive – £10 in 1968 as opposed to £5 for black & white and £1.25 for radio only. Bizarrely, you can still buy a black and white licence now and last year 5000 people did! A colour TV was estimated by the BBC to cost £250 in 1967. That is a sizeable amount of money – in perspective you can buy a 32-inch colour TV in HD for much less than that today – 54 years later. So, it gives you the idea that very few people of the approximately 8 million who tuned in (if you simply apply the percentages, an imprecise method, but the best I’ve got), around 56,000 people would have watched ‘Spearhead’ in colour, many simply couldn’t afford to and many either couldn’t afford or didn’t want a TV at all. Colour TV’s were a status symbol, a luxury item largely for the rich and those with high disposable incomes in 1970. This was a time when many rented TV’s anyway. No wonder The Master requested one in 1972’s ‘The Sea Devils’ – I mean public enemy no. 1 wouldn’t want to slum it with the masses and watch ‘The Clangers’ in black and white, would he?

A natural progression?

Most of season 7 (‘Inferno’ aside) was commissioned and worked on by the 1960’s team of either Derek Sherwin or Peter Bryant producing and Terrance Dicks script editing. Despite often feeling like a new show, it is a continuation of series 6 in that regard – complete with some of the attendant scripting issues, primarily with ‘Ambassadors of Death’. It is Sherwin’s vision for the show, not Terrance Dicks’ – in fact, he didn’t approve of the changes at all. Barry Letts isn’t involved in ‘Spearhead for Space’ to any extent, he even misses most of the location work for ‘The Silurians’. ‘Inferno’ is the first story that he has a hand in commissioning and he even partly ends up directing. Peter Bryant isn’t credited here, but he is still there, working with Sherwin (it was him that organized Bessie for the second story for example) – although what he was doing apart from that, well who knows. Mostly propping up the BBC bar if Terrance Dicks is to be believed and about to start ‘Paul Temple’, taking Sherwin and Trevor Ray (who was doing some season 7 associate script editing) with him.

Really though, the show was moving towards this point anyway, just over a long period of time. Aside from the Coal Hill parts of ‘An Unearthly Child’ we only really get a few glimpses of contemporary Earth in the earlier part of the Hartnell era – ‘Planet of the Giants’, the leaving sequences for Ian and Barbara (and a glimpse of ‘The Beatles’ ) in ‘The Chase’, the cricket match and police station in ‘Daleks Master Plan’), Dodo joining on the common at the end of ‘The Massacre’ – so just bits and pieces in bigger stories. Gerry Davies and Innes Lloyd change all of that. And the thread that leads to ‘Spearhead from Space’ really starts with ‘The War Machines’ – the Doctor on the streets (and nightclubs!) of swinging London battling a homegrown menace and helping the authorities and army. Assuming the role of brilliant but eccentric scientist helping against invasions – the wartime boffin or professor beloved of 1950’s sci-fi stories. This continues through stories such as ‘Tenth Planet’, ‘The Faceless Ones’, ‘Web of Fear’, ‘Fury from the Deep’ and of course ‘The Invasion’. Some of these are set in the ‘near’ future – but really, like the UNIT years, they might as well be contemporary – dealing with real world events and changes – the Apollo rockets, package holidays, consumer electronics, the switch to North Sea gas etc.

‘Web of Fear’ and ‘The Invasion’ are of course particularly important to what would become the season 7 format and ‘Spearhead’ in particular. They establish firstly Colonel/Brigadier Lethbridge Stewart as a character and UNIT – establishing its MO and role as a UN organization, supported by the British army. Watching them together though, ‘Web of Fear’ feels like a tense, claustrophobic wartime drama – a British War film, whereas ‘The Invasion’ feels more like a spy adventure thriller – more The Men from Uncle’ , with a soundtrack form ‘The Ipcress File’– one almost of the 1940s/50s and one of the 60s’.

Both of these stories are referenced in ‘Spearhead’ by both the new Doctor and the Brigadier – they are acknowledging that although the exile to Earth is a new departure, the seeds of the format were established 2 years prior to its transmission. The continuity is light touch though – ‘Spearhead’ is a fine jumping on point for new viewers. I’m sure when I was very young, I just thought that the Doctor was a human scientist, who lived on Earth and stopped alien invasions, while driving round in Bessie. That that was the format, not the wanderer in time and space, exiled from his own people. One thing that works very well though is that due to the continuity of production personnel, particularly Terrance Dicks, despite all of the change, this all feels part of the same show when you watch it in a marathon. The look and feel might be very different, but it isn’t a hard reboot jettisoning the past completely. It’s all very odd though – it is a big format change – think about the change from season 1 or 2 in just 6 years, but it is oddly familiar at the same time. It is very, very clever – although probably a lot of that is by accident!

I’d argue that season 7 is a bridging season really, a thing of its own. ‘Spearhead’ itself is more like a glimpse into what the show could have been if it had more money and BBC attention – rich looking, filmic, competing with contemporary ITC American funded series and despite what I’ve already said, in colour. Id’ love to see the rest of the season on film and restored beautifully, but that isn’t what we have unfortunately. Rather we have patchwork of video, film converted to video, colour reverse standard converted from US NTSC video recording of film. Some of these stories were in black and white the first time I saw them – ‘Ambassadors‘ looked pretty amazing, quite startlingly gritty in that format. It is such a shame though. A question often asked is could the season 7 format have been sustained in the long term – well I’m probably different from most people in that regard, but I’ll discuss that more in as the review progresses.

Introducing the band…

In my first piece, I referenced the fact that ‘Spearhead’ has a lot of work to do – it has to establish a new format, new assistant and new Doctor, all while telling a story and setting down a marker for the future of the series. More than that it has to establish a future for a series on the brink. It does all of this effortlessly. Holmes throws all of the techniques available to him to introduce the new framework and to tell the story – new characters who come to the story who require information to explain the setup, existing characters returning to inform them of the story so far, the media asking questions, briefings, a medical investigation, even a disgruntled employee turning up to find out what has happened to his job. It is all very artfully done and is highly reminiscent of the way that Nigel Kneale approaches storytelling. He used journalists, TV, radio, voxpop, police investigations, pub gossip, everything to disguise the controlled release of information. Holmes by luck or design or just convergent evolution follows that same process. All of which stops the joins from showing and disguises the sheer amount of information being imparted, it is terrific craftsmanship. It is simply light years better than the work that Robert Holmes has produced thus far. It is also very much to the credit of Terrance Dicks that he championed Holmes and approached him to write this opener, neither of his first two stories were all that great, more solid than anything, but he did possess a useful attribute – that of being able to deliver completed, workable scripts – a rarity in the late 1960’s.

Perhaps my favourite technique that Holmes employs is to fill in the back story via what is essentially a job interview. UNIT as an organisation is re-introduced for existing viewers and explained for new viewers alike through the eyes of their new, rather unwilling recruit – Dr Elizabeth Shaw. This setting allows the Brigadier to fill her in with not only the backstory of UNIT, the Doctor and the previous invasions, but also the current situation – the lack of the Doctor and the meteorites that have mysteriously landed, tying back to the radar crew at the start of the episode. Her cynicism and incredulity, plays the part of any of the audience who might share her doubts at the new format or the show in general. It helps of course that Nicholas Courtney is such a charming actor, it is his amused, wry observations that really make those scenes with a nervous Caroline John.

She will go onto much better things though, she is a terrific actor and already she makes Liz a distinctive new addition to the show, even in comparison with Zoe – closer in spirit to Barbara, but also something rather different. Poor Liz though – dragged off to an unwanted job for the military, head hunted by the Brigadier due to her exceptional skills and qualifications. She is normally the smartest person in any room. Then she finds out that she is only the second choice for the job! She goes from annoyed, to sceptical, to intrigued, to piqued in the space of a conversation! Then she meets the first choice candidate and he waltzes in and takes the job she didn’t even knew she wanted, relegating her to his very over-qualified assistant. Terrance covers this very well in the novelisation, including the point at which Liz’s hostility wanes and her scientific curiosity takes over:

The Brigadier seemed lost in his memories. ‘Though, of course, we weren’t alone. We had help. Very valuable help.’ He looked up and smiled. ‘To be perfectly honest, Miss Shaw, you weren’t my first choice for the post of UNIT’s Scientific Adviser.’

Despite herself, Liz felt a bit resentful. ‘Oh? And who was then?‘

‘A man called “the Doctor”,’ answered the Brigadier.

‘Doctor?’ said Liz. ‘Doctor who?’

The Brigadier chuckled. ‘Who indeed? I don’t think he ever told us his name. But he was the most brilliant scientist I have ever met. No disrespect, Miss Shaw.’

‘So why didn’t you get this mysterious genius to be your Scientific Adviser, instead of practically kidnapping me?’

‘Don’t think I didn’t try,’ said the Brigadier ruefully. ‘Unfortunately, he tends to appear and disappear as he pleases. I tried to get hold of him when they decided we needed a resident scientist. The Intelligence services of the entire world were unable to turn up any trace of him.’

‘So you decided to make do with me?’

‘And a great success you’ll make of it, I’m sure,’ said the Brigadier. Liz couldn’t help smiling at the compliment. Despite his stiff military manner, there was something very likeable about the Brigadier.

And then:

Liz Shaw hesitated for a moment. She realised that this was her last chance to insist on her rights, to refuse the ridiculous hush- hush job she was being offered and return to the quiet, sane, sensible world of scientific research.

‘Shall we go, Miss Shaw?’ repeated the Brigadier.

Liz looked at him and saw the appeal behind the formal manner. Suddenly she realised that the Brigadier really was worried, that he really did need her help. Why me, she thought, why me? There must be heaps of people better qualified.

But she also realised that she was now much too caught up in this mysterious business of invading alien forces, intelligent meteorites and mysterious men with police boxes, to draw back now. If she did, she’d be torn with curiosity for the rest of her life. She got up and strode to the door which the Brigadier was holding open for her. ‘Come along then, Brigadier,’ she said briskly, ‘what are we wasting time for?‘

The Brigadier stood astonished as Liz strode past him and marched off down the corridor. Then, deciding not for the first time that he would never understand the ways of women, he hurried after her.

I will return to Liz Shaw later in the review. As you will find, probably not to any great surprise, I think she is rather wonderful!

And so to the new Doctor. Well he is just brilliant from the start. The story does something that ‘The Christmas Invasion’ will do years later – holds back the new Doctor and then unleashes him part the way through, the absence magnifying the brilliance of the new arrival. Pertwee’s arrival may lack the cockiness of Tennant’s opening performance, but it is no less confident and effortless. He is an absolute star turn, he might not be an actor in the league of Hurt or Eccleston or even McGann, but he is a star. Charismatic and compelling. He is also brilliantly suited to playing the Doctor, just like his successor, Tom Baker would be, he was born for this. Like Tom or David, his look is also just too perfect – it just looks so right on him, that perfect silhouette. It is also so right for that time 1969/70. Adam Adamant meets Jimi Hendrix with a hint of John Steed for good measure – brilliantly well judged.

What we initially get from the new Doctor are a few comedy set pieces (the shower scenes or the escape in the wheelchair), the like of which will be sprinkled across his era, lulling us into thinking that maybe he won’t be so different to Troughton after all. Then he turns up at UNIT HQ and just takes over, haranguing the poor commissionaire (Derrick Sherwin – essentially his boss at the time!) – just like he will do to many a civil servant, politician or pen pusher – and then effortlessly charms the Brigadier and Liz into accepting him. Next minute he’s a naughty schoolboy, tricking Liz into stealing the TARDIS key for him – ruefully apologising once caught. His hangdog childlike expression on realising the secret of the TARDIS has been taken from him. Next he’s the brilliant scientist investigating the sphere and devising a method of exploring the intelligence within it. Then man of action, taking the fight to the Nestenes at their lair. I just love spending time with his Doctor – he is by turns funny, charming, brave, pompous, vain, childish, fiercely moral, exceptionally rude and utterly, utterly brilliant. He was in short, my hero – and it is all there immediately, fully formed in the second half of this story. All thoughts of series cancellation evaporate immediately.

Phenotypic plasticity or how to adapt, survive and conquer new worlds

“The ability of an organism to change in response to stimuli or inputs from the environment. Synonyms are phenotypic responsiveness, flexibility, and condition sensitivity. The response may or may not be adaptive, and it may involve a change in morphology, physiological state, or behaviour, or some combination of these, at any level of organization, the phenotype being all of the characteristics of an organism other than its genes.”

M.J. West-Eberhard, Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2008

“Channing and Hibbert stood silently, almost reverently, beside the huge tank. The creature inside was much bigger now. It could be seen moving and struggling with restless life, as if ready to break out. Channing adjusted more controls to speed up the flow of nutrient. Hibbert asked in a kind of fascinated horror: ‘What will it look like when it is ready?’

Channing straightened up from the controls and looked at him impassively. ‘I cannot tell you that.’

‘But you must know,’ protested Hibbert. ‘You made it.’

‘I made nothing. I merely created an environment which enabled the energy units to create the perfect life form.’

Hibbert rubbed his forehead. ‘Perfect for what?’

‘For the conquest of this planet,’ said Channing coldly. “

Terrance Dicks after Robert Holmes 1974

The idea at the heart of ‘Spearhead from Space’ is rather brilliant – an alien consciousness that can animate plastic and manipulate it to provide a form appropriate to survival and conquest of other worlds. The ultimate in phenotypic plasticity. Rather than ‘terraforming’ a planet to suit your needs, adapt your form to fit the planet – problem solved. A rather neat solution to the problem that Nigel Kneale hits in ‘Quatermass II’ where the ‘Amonids’ require their own atmosphere created with the ‘meteorites’ and the pressure domes at the plant at Winnerden Flats. I find myself marvelling at Robert Holmes sometimes, he had such an aptitude for this material – in a way that few other writers do. He was just highly skilled at devising concepts that are both fantastic and yet believable and then selling them to us as if they were entirely real. I mean that’s a terrific idea – no scratch that, a stone-cold genius idea. So brilliant, that I’ve no doubt Derrick Sherwin claimed it as his own!

What a brilliant way to colonise other planets, coming in an era prior to the idea of nano-technology, but also brilliantly utilizing something that was becoming ubiquitous in late 60’s/early 70’s households. I will return to this central conceit more in when I cover the sequel ‘Terror of the Autons’ for obvious reasons, but we take this for granted a little bit I think. It is brilliant in that it has the high concept thinking of Nigel Kneale, but very much married to the everyday and household – and that is very ‘Doctor Who’. Victor Pemberton had done something similar with natural gas in ‘Fury from the Deep’ or Mac Hulke with package holidays in ‘The Faceless Ones’ or even Haisman and Lincoln juxtaposing the uncanny with the London Underground in ‘Web of Fear’. I suppose you could argue a similarity between the Nestenes/Autons and the Intelligence/Yeti – however despite that they feel like they come from different traditions, with the earlier stories perhaps finding more of an echo in the horror of Holmes’s ‘Pyramids of Mars’ – ancient gods and robot servants etc. While ‘Spearhead’ very much beds the alien menace in the ‘now’ and in the familiar, in the modern and in this case right in the high streets and households of the viewers. No wonder the concept has been revisited numerous times.

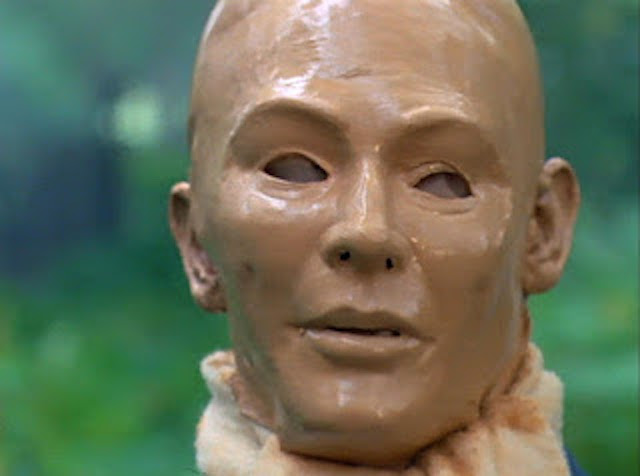

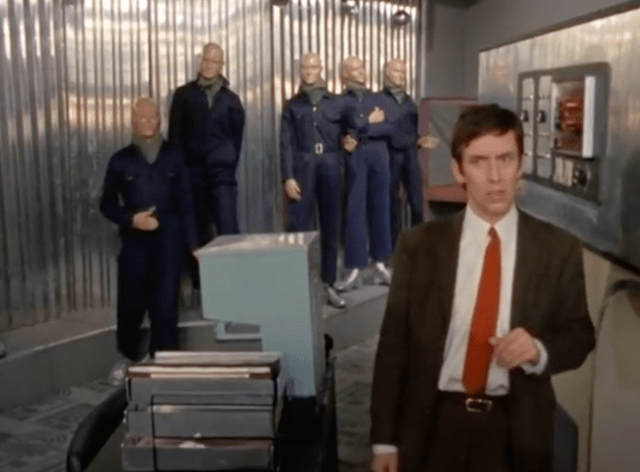

That central conceit of an entity that can control and manipulate plastic opens up all sort of nightmarish possibilities, which this story and its sequel only partially explore – many more still remain to be exploited. It amazes me that the new series hasn’t really attempted to do this, despite multiple appearances for the Autons. Recently, it even ignored the possibilities of exploring plastic waste as an issue through this mechanism and instead opted to invent an entirely new one to do effectively the same job. Here though, well it gives us some of the most enduring images in the show’s history. Ransome being stalked by an Auton in the plastic factory – the figure silently stepping off a platform in the background. The figures in Madame Tussauds – tapping into that sense of unease that people might themselves have experienced when viewing replica waxworks there. The body horror of Scobie meeting his waxen-faced duplicate face to face. And of course, the shop window dummies coming to life and rather mercilessly gunning down members of the public on Ealing Broadway.

That last image is one of the show’s most iconic in its history – so much so that it was repurposed for the return of the show in 2005. It is easy to take for granted, but it is simply brilliant. It feels incredibly real, especially to anyone who remembers the city streets of the 1970’s. Gloomy and slightly grimy, with early morning commuters and policemen on the beat. It is a very British scene – a queue at a bus stop and then a very casual slaughter. So iconic is it, that it seems amazing to think that it isn’t in one draft of the script. Holmes cut it and instead the Autons attack UNIT HQ disguised as MI5 operatives and shoot Munro in the process. Thankfully it was re-instated in the next draft. In the story outline Holmes rather laconically describes it as:

FILM MONTAGE

Whatever we can manage of shop window Autons coming to life and attacking key points.

If you read any of his story outlines, that is a fairly typical Holmes comment! The whole thing is reprodcued in Richard Molesworth’s Robert Holmes biography.

The shop window dummies, like the Tussauds waxworks are replicas that whilst realistic to some extent, also are just wrong – a distorted image of a human face and engender a sense of unease. I think it is because the visual representation of the face is a primary method we use for recognition and identification of an individual, as such it is fundamental to our self – but anything that disturbs that is unsettling to us. The face is also key to our understanding of what others are trying to communicate, to their emotional state – as such it is fundamental for empathy and understanding. The blank, eyeless face mask of the Autons, takes the show in a similar direction, although much less explicitly so, as ‘Robots of Death’. With the distortion of the human form, one without body language or tell-tale non-verbal signals. The attempt to replicate the human in plastic becomes horrific, a terrible parody of the form.

Beyond that, though the shop window dummies are such a familiar sight on British streets, having them step out of a shop window and into our nightmares is incredibly clever and very, very Robert Holmes. Even outside of the set-piece scenes I’ve already detailed, there are a plethora other iconic moments that just linger in the memory – the footage of a dolls face being pressed in a factory juxtaposed against Channing. Or the beautifully shot image of Channing staring at the Doctor, Liz and the Brigadier through the distortion of frosted glass. Or in the sequences of first Meg Seeley and then UNIT confronting the Auton at the Seeley’s cottage. There are many more that I could highlight. The story is punchy, pacy and replete with set piece moments to scare, horrify and ratchet up the tension.

To my mind, the Autons themselves are far more effective in this story than any of the sequels. There are a range of reasons for that. Those masks are really quite disturbing – unsettling in the way that dolls are, eyeless and slightly glistening, a parody of a human face. The simplicity and crudeness of the mask and its lack of flexibility all actually count in its favour. There are some similarities to the Cybernauts in ‘The Avengers’ (more to come on that), especially in the scenes where the Auton silently follows Ransome via his brain print and cuts into the tent or when it is tracking the signal of the swarm leader in the woods. Also, whilst fulfilling the role of silently stalking or relentlessly following you creeping ‘Doctor Who’ menace, they can also run! Bloody hell what were they trying to do to us? We can’t even run away. And then there is the hand, which falls away to reveal the barrel of a gun. It really is nightmarish stuff. Also, I think that the silence of the Autons, is rather important, they are impassive, barely animate, relentless and unfeeling – how do you kill something like that – that isn’t actually alive? As such it feels like a real misstep in ‘Terror of the Autons’ to have an ‘Auton Leader’ who talks.

And talking of which… the piece de resistance in all of this is Channing. Hugh Burden in that role plays an enormous part in selling all of this, it is a brilliantly creepy performance – unsettlingly odd, without ever pushing it over the top. He plays a similar role that say Bernard Archard as Marcus Scarman would fulfil in ‘Pyramids of Mars’ or Wolf Morris as Padmasambhava in ‘The Abominable Snowmen’– a more obviously human mouthpiece for the alien menace. He is different, in that he is ultimately revealed to be just another Auton, rather than a possessed human puppet, but the role is equivalent and works extremely well. He has a way of staring without blinking that is tremendously unsettling and creepy – such that now when I meet people who naturally blink less frequently, it really starts to give me a sense of unease. All this is achieved through acting and maybe the hint of a smear of Vaseline! To my mind, he deserves to be remembered as one of the great ‘Doctor Who’ villains.

A collective consciousness

The Nestenes themselves were originally conceived by Holmes to have existed in great hives across the planets they inhabited. As they are depicted here, the Nestenes ar e a gestalt, agroup creature – a telepathic hive mind with multiple physical forms all connected. It feels very much in keeping with Nigel Kneale’s first two ‘Quatermass’ serials – the thing that Victor Carroon becomes a collective organism, an amalgam of him and his colleagues and various other absorbed organisms and also the ‘amonids’ of ‘Quatermass II’, more later on that.

We get hints of this, when The Doctor recognizes the nature of the organism and tries to communicate with the fragment of the consciousness contained within the ‘swarm leader’. It is interesting looking at this scene, the effect of Liz Shaw in the dynamic, with the Brigadier asking the questions the audience would, albeit in an intelligent way and Liz being given some of the explanations that the Doctor would normally provide. We’ve seen a little of this with Zoe in the past, but this feels rather different:

BRIGADIER: What are you actually trying to do, Doctor

DOCTOR: Well, it appears that in there we have what one might loosely call a brain. Fifty megacycles, Liz. If we can establish the frequency on which it operates

DOCTOR: Oh, dear.

LIZ: We overloaded the circuit, I think.

BRIGADIER: Doctor, you were saying that this is some kind of brain.

DOCTOR: Yeah, or part of a brain. An intelligence. Yes, that’s probably nearer the mark.

BRIGADIER: Sending signals somewhere. Where to

DOCTOR: Well, the rest of itself, surely

LIZ: The other globes that came down. They’re all part of one entity. Let’s say a collective intelligence.

BRIGADIER: Can it see us

DOCTOR: My dear fellow, it’s not sentient.

LIZ: No, our measurements prove there’s no physical substance inside it.

BRIGADIER: But, if it is has no physical form

DOCTOR: No, once here it can presumably create a suitable shell for itself. Otherwise there’d be no point in coming.

LIZ: The plastics factory.

DOCTOR: Yes.

It is in the final confrontation scenes at the plastic factory that we learn most about their nature:

CHANNING: You’re too late.

DOCTOR: On this planet, there is a saying that it is never too late. Good gracious! What on earth is this thing

CHANNING: A lifeform perfectly adapted for survival and conquest on this planet.

DOCTOR: Is that what you look like on your own planet

CHANNING: No. We have no individual identity.

DOCTOR: So this thing is a sort of collective brain, nervous system

CHANNING: Humanly speaking, yes.

DOCTOR: Oh, but I’m not human. So, if you live as a group, you can be destroyed as a group, surely

CHANNING: You cannot destroy us.

DOCTOR: I destroyed your facsimile of Scobie, therefore I can destroy all of you.

CHANNING: No one has the power to destroy us, not even you. We are indestructible.

The Nestene itself, well, to those of us of the Target generation, the creature will always be a letdown. That isn’t the fault of those making the show – we were never going to get the creature of our childhood imagination and nightmares. I mean, how could it?

A huge, many-tentacled monster something between spider, crab and octopus. The nutrient fluids from the tank were still streaming down its sides. At the front of its glistening body a single huge eye glared at them, blazing with alien intelligence and hatred.

It is noticeable that the creature doesn’t even exist in the scene breakdown for Robert Holmes’s original story outline,. The confrontation is with Channing and the Autons alone. It is a later addition, feeling rather like the Hammer version of ‘The Quatermass Experiment’ – with a tentacled octopus creature high in Westminster Abbey.

The ending is definitely the weakest link here and apparently the final shots of the death of the creature were reshot, so I hate to think what these were originally like. They are clumsy – with the device clearly unplugged, but the hyper-intelligent Liz failing to spot this and Jon’s gurning as the creature wraps its tentacles around him – a rare misstep in what is a very impressive debut for the lead. And yes, the creature – well it isn’t exactly impressive, there are probably better ways that could have done, not exactly an unusual situation for ‘Doctor Who’ – but it stands out here more as the rest of the production is so impressive and accomplished. In 1969 though, productions with much higher budgets would have struggled to do anything much more impressive, but I think this is also a moment where the clarity of the 16mm film is counterproductive, something darker and murkier would have been advantageous.

With regard to the mechanism for ending the menace, well I’ve seen others criticise this aspect of the story, but I’m fine with it – we’ve seen the Doctor toiling to build something that can disrupt the Nestene collective consciousness. And then he has to use it. The Nestene is a group creature, a hive mind, he doesn’t kill it, he can’t, Channing makes that clear, he just cuts off the signal to the group, the group goes on.

LIZ: Basically, it’s the same as an ECT machine. Electric convulsion therapy.

DOCTOR: Only much more powerful, of course.

BRIGADIER: Well, it worked. Doctor. These Nestenes, will they try again?

DOCTOR: Possibly. They’re telepathic, so they certainly know what happened.

Although Holmes’s original breakdown makes more of the Doctor offering a way out to the Nestenes, with a separate plot strand as Liz is waiting to broadcast a signal to defeat them from Broadcasting House. I wish they had kept the appeal aspect of the ending, as it would fit very well with the new Doctor, who would take his moral responsibilities in that regard much more seriously than his predecessors – offering the aggressors a peaceful way out. Something which will be developed across this season – the Doctor as mediator, using his unique position on Earth.

What I do love though, is the sense that it has taken time and effort to defeat the menace. We get the Doctor and Liz working through the night and the dawn bringing the start of the invasion. I’m not a huge fan of throw some solution together and quickly turn off the plot (I’m thinking of ‘New Earth’ and similar) and it is something that season seven does very well – people do science – it might be highly compressed in terms of normal scientific experimentation and testing – but at least it makes an effort to show that scientific solutions take time and require hard work – even for the Doctor. It heightens the sense of jeopardy and the scale of the menace as well and is part of stranding the Doctor on Earth, without crucial memories and a functioning TARDIS.

A new sense of direction..

I didn’t want to leave this story (don’t worry – there is a fair bit more to come on this!) without recognizing the great contribution that the director Derek Martinus makes to its success. He isn’t someone I knew a great deal about, so I decided to do a bit of research. He was of Dutch descent via the family trade at Smithfield market. His great love appears to have been theatre directing – in both the UK and Sweden, where he met his wife. He directed a wide range of drama for the BBC – the football soap ‘United!’, ‘Z Cars’ and plays and costume drama like ‘Penmaric’. Looking at his work outside of the BBC though, I came to the conclusion that he might have been happier directing Strindberg or Ibsen, but the one online interview I found didn’t indicate a resentment towards the show.

As a ‘Doctor Who’ director, he is difficult to assess, as most of his stories have missing episodes to at least some degree. ‘Galaxy 4’ has one relatively recently recovered episode, plus a long clip. ‘Mission to the Unknown’ is entirely missing, ‘Tenth Planet’ missing the final episode, ‘Evil of the Daleks’ only has one surviving episode of seven and it isn’t the most interesting one from the perspective of what he could achieve visually. Even ‘The Ice Warriors’ has missing episodes. What we do have of these is mostly studio bound, limiting what a director could achieve – I mean even Richard Martin’s location work is superior to his studio bound stuff. Of those surviving episodes, well they are all pretty good, but ‘Spearhead from Space’ is in another league altogether.

This is all beautifully shot. I mean he really deserves huge plaudits for this. I am not sure if it is the amount of location work or just being able to shoot on lighter film cameras – or indeed film itself, but this is very much in the top echelon of classic Doctor Who stories in terms of direction. Even simple things like the moving tracking shots of the Brigadier and Munro walking in the hospital corridor or the terrace outside or the in your face, documentary style scenes of the Brigadier at the hospital surrounded by journalists, with Channing framed in the background. It is just so obviously dynamic. My favourite shot though, is of Channing looking through the frosted glass at the Brigadier – a simple idea but brilliantly conveying the strange, unsettling quality of the character. This is all a cut above any of the surviving direction of the 60s shows – with the exception of Douglas Camfield or possibly Michael Ferguson. It is as if modern direction has caught up with the show at last – something that would be consolidated in this season by Ferguson and Tim Coombe and would usher in a period of great direction from the likes of David Maloney and Camfield.

The story doesn’t pull it’s punches either – I mean there are plenty of fun scenes with the new Doctor (the Delphon eyebrows or the infamous shower scene), but some of the other sequences are very hard hitting, typically 70’s action series. A prime example is the crash of the UNIT land rover, swerving to avoid the Auton and the aftermath of smashed windscreen, prone body and blood. The camera racing towards the figure of the Auton in the road, as if we were in the driving seat ourselves. The death of Ransome is similarly visceral – as are the two battles between UNIT and the Autons. Martinus makes the most of all of this, with only the ending being below par, although not to the extent of impacting on the show as a whole. The rest is impressive stuff and you really feel you are watching a much more expensive, professional show than we’ve previously seen.

This is especially true or possibly because of the circumstances surrounding the production, given that the show was nearly lost to industrial action and a new approach was required to save the production:

‘That first one we nearly lost and only saved because Derrick Sherwin, the producer, was a very energetic and determined bloke. He had a tremendous fight to get the go-ahead, but he did and for a while we all had this wonderful fantasy of doing ‘Doctor Who’ all on film and selling it to America.’

For his faults and his habit of claiming credit for an awful lot of stuff, to the obvious amusement of Terrance Dicks, Derrick Sherwin also deserves plaudits for this. His stamp is all over season 7, a real favourite of mine, but saving ‘Spearhead from Space’ and giving us a glimpse of what ‘Doctor Who’ might have been like in the 1970’s, if it had any money spent on it, well I’m really grateful to both of them. Sadly this also represents their final credit for the show, but they bow out in real style.

A four-part wonder?

In an outlier of a season, ‘Spearhead from Space’ is an outlier in of itself. It is a four-part story in a sea of seven-parters. The four-part story architecture would become the standard format of the 1970’s, with fewer 6-parters and the odd 5-part story thrown in. At this point though they aren’t quite the mainstay that they would eventually become – I make it 22 stories out of 50, as opposed to say 16 x 6 parters and the rest a smattering of 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 or 12-part stories. I think that the 4-part structure works so well because the framework is simple and the role of each episode within the narrative structure is clear and easy to follow. Episode one sets up the world and our heroes explore it, ending on reveal of menace, episode two we learn more about the world and the nature of the menace, episode three builds up the tension and jeopardy towards the finale and episode four resolves everything. Add in two or three extra episodes and you are left with adjusting the format or adding a couple of episodes – usually episodes 2-3 elongated to 2-5 of some kind of jeopardy, additional world-building or repeated escape/recapture routines. Re-thinking the approach for a 6 or 7-part story generally works better to my mind.

Revisiting the Pertwee era in the 1990’s on VHS, one thing that became clear to me is that the approach to 6-part stories didn’t often work all that well. Now that is generalization, there are exceptions – for example ‘The Green Death’, but there are plenty of examples that sag in the middle episodes and outstay their welcome. This is particularly true of stories like ‘Monster of Peladon’ or some of the Mac Hulke stories – prime examples being ‘The Sea Devils’ or ‘Frontier in Space’ – both of which I love, but have to admit that there is an awful lot of filler – escape and recaptures that push their luck at least one too many times. The scripts even tacitly acknowledge this on occasion. Even when they change location – the moonbase prison/Ogron planet or the submarine/Sea Devil base – it is often just to get captured and escape again. The filler that is more interesting generally are the times that Jo and the Doctor and/or the Master spend get some nice character moments together. All of which is a bit strange, given that Terrance Dicks is so good himself on structure and shape. Looking back to the approach that season 7 takes would have helped I think.

So, let’s imagine what ‘Spearhead would have been like as the seven-part story. In the longer 7-part stories, the story heads in a different direction to support those extra episodes often becoming something rather different in the process. Rather like the method that Robert Holmes uses when structuring ‘Seeds of Doom’ with Robert Banks Stewart as a 2/4 or the approach that Steven Moffat takes to two-part new series stories, each of the season 7 stories pulls a similar trick to utilize the 7 x 25 minute episodes fully. ‘The Silurians’ reaches the point where the story would normally wrap up and inserts the brilliant virus pandemic sequence, which takes the story to a very different place – jumping from caves in Derbyshire to the impact of the virus in the capital. ‘Ambassadors of Death’ takes the Doctor off into space as an astronaut – away from the warehouses, industrial complexes and space control of the other episodes, to the psychedelic world of the alien spaceship. Lastly, ‘Inferno’ doglegs off to the parallel world strand. Each of those stories are improved in my view by those episodes. Is there anything like that, which would improve ‘Spearhead from Space’?

In the context of season 7 or even some of the longer stories of season 6, ‘Spearhead’ actually feels like the edited highlights of a longer story, just as many years later ‘Rose felt like the vastly edited highlights of a classic 4-part story. And whilst I wouldn’t change the story in the slightest, it is almost perfect, there are aspects of it that are left unexplored or appear slightly undercooked. The obvious thing lacking from the story is the proper exploitation of the ‘conspiracy’ setup – the replacement of senior government and military figures with replicas. We get Scobie obstructing the Brigadier and collecting the energy sphere, but that’s it apart from the brief confrontation at the plastics factory. With more time, that could have been expanded and explored to good effect.

One of the key influences on the story – ‘Quatermass II’, makes much more use of the cold war paranoia and political conspiracy/cover-up aspect of the story. With 6 x 1/2 hour episodes to utilize, Nigel Kneale has Quatermass at Whitehall, amongst a committee of possessed politicians and civil servants, each of them carrying the mark left by the alien influence. Adding to the sense of creeping paranoia and body horror. His potential ally, the campaigning MP, Vincent Broadhead is taken over by the alien intelligence in the corridors of power (well a parliamentary committee room) and Quatermass escapes to investigate the synthetic food complex. He then also throws in a workers revolt at the plant at Winnderden Flats, as they become aware of what they have built and the nature of the menace.

There is a fair bit of potential in this a plot element in ‘Spearhead’, but none of the Nestene/Auton TV stories really exploit the duplicate human strand properly – largely to allow the stories to power along and be pacy and action packed, it is used sparingly in short set-pieces. In this story the replicant strand never really goes anywhere. Not that this is overly obvious – it is replaced with a sort of velocity of storytelling that we hadn’t seen much of until this point. Like ‘Rose’ years later this four-part version really motors along. You could imagine though a slightly different version of the story that pauses to build the creepiness of the menace and instead for a couple of episodes becomes a political conspiracy thriller. In one version of the script, Auton MI5 agents come to reclaim the Nestene energy unit from UNIT HQ. Imagine two episodes as the Brigadier has to fight his way out the Whitehall as the government have been replaced by Auton replicas. And then the remnants of the UNIT team have to go on the run from homicidal waxworks and humans under orders to protect the Plastics factory. The waxworks strand as it is doesn’t really lead anywhere and Scobie is the only use the story makes of an aspect that elsewhere might have been an entire story on its own (‘The Faceless Ones’ for example).

Would that be a better version? Well I think in a different context within season 7, it might. It would get to build the creeping menace and play up the government conspiracy angle. However, as an opener, I am inclined to think not. It is the sheer punchiness of the story that starts the era off with such a bang. The rest of the series is then allowed to be more expansive and explore the not always smooth relationship between the Doctor and Brigadier and especially with wider officialdom as he adjusts to life in exile. With Liz often acting as a mediator between them. The first year of the Doctor’s exile is less cosy than things will become when Jo turns up. I wouldn’t miss all of that for the world, but I am still left with the feeling that I wanted more of season 7. No, I think I’ll stick with ‘Spearhead from Space’ as it is – a punchy blend of Nigel Kneale, ITC action and ‘Doctor Who’, but there is more of ‘Quatermass II‘ to follow before I am finished with this story and I’ll expand on the similarities between it and this story and also the other influences on ‘Spearhead from Space‘ next.

Quatermass 2 Adam Adamant 1?

Soldiers at an army tracking station detect incoming meteorites on their radar screens. A country ‘yokel’ witnesses their arrival and discovers one buried in a field. Politicians and army officers are changed or possessed by exposure to something from the meteorites, which contain an alien consciousness, which when transferred to tanks in an industrial facility create thrashing monstrous bodies for the alien intelligence. Luckily a brilliant scientist, with his team is there to foil the attempt by the aliens to take over the planet. That scientist’s name is of course Bernard Quatermass and the story is ‘Quatermass II’.

A man out of time wakes up in hospital in late 1960’s Britain. He’s unsure of where he is, when it is or indeed who he is. He escapes in a Doctor’s coat. He will turn out to be a dashing Victorian hero, clad in cape, smoking jacket and bowtie – zipping about London in an unusual vehicle (for him at least), fighting evil and injustice in the BBC’s answer to ‘The Avengers’ or the ITC action shows. The hero’s name of course is Adam Adamant.

A man from space is in a hospital bed. Reporters gather outside looking for a story. Faceless men attempt to kidnap the ‘space man’, but he manages to escape from their vehicle and go on the run. The man from space is Victor Caroon and the story is ‘The Quatermass Experiment’

A blank faced figure homes in on beeping signal and smashes his way into the house as he advances on his target. A gentleman hero in his vintage Bentley car, with a clever female sidekick is on hand to save the day. The figure is a Cybernaut and the show is ‘The Avengers’.

Army radar operators follow a UFO as it crash-lands nearby. A ‘man’ is hit by a vehicle. The Doctors at a nearby cottage hospital treating him realise from his X-rays that his physiognomy is alien and his blood is no known type. The film is ‘Invasion’(1966) from a storyline by Robert Holmes.

While writing this review I was reminded of recently watching ‘The Third Man’ – an excellent documentary on the season 10 “Doctor Who’ Blu-ray collection. When asked by Mathew Sweet, Steven Moffat replied that the main thing that the new approach for season 7 brought to the show was Hammer’s film version of ‘Quatermass & The Pit’ – the setup between Colonel Breen (and the army bomb disposal squad) and Quatermass and the intelligent female assistant Barbara Judd. Mark Gatiss (correctly) interjected that that wasn’t quite right, it had a lightness of touch and it was like ‘Quatermass & the Pit’ with ‘Adam Adamant’ added into it. I’d amend that further – it is rather more like ‘Quatermass II’ with Adam Adamant added in, a touch of John Steed and Mrs Peel and the feel of the ITC film action shows. In short, it is all of my favourite things.

Really though, this is the point at which Robert Holmes steps away from the also rans and starts to exert his brilliance on the show. Derrick Sherwin says to him ‘let’s do this like Quatermass’, so Bob rolls up his sleeves, fills up his pipe and says ‘you want ¤¤¤¤in’ Quatermass, I’ll give you ¤¤¤¤in’ Quatermass!’ And he does. Nigel Kneale once said that he tuned into an episode of 70’s ‘Doctor Who’ and saw his own work on screen – now there are a quite a few options for the story in question – ‘Image of the Fendahl’ for example or aspects of ‘The Daemons’ or ‘Seeds of Doom’ or ‘Ark in Space’ – but none run quite so close as ‘Spearhead from Space’ – the opening scene is almost identical and there are so many other similarities. I am going to review ‘Quatermass II’ next, so if you haven’t seen it before – well firstly, who not? Secondly, I will try to draw out the similarities and differences between the two productions as best I can.

Holmes once claimed never to have seen “Quatermass II’ – I’ve no reason to disbelieve him, but if that is the case there are an awful lot of coincidences here. You see, I love Nigel Kneale and his work, the brilliant, curmudgeonly, crabby old bugger that he was, but to my mind Bob Holmes is just as clever – and prophetic and deserves to be remembered in the same way. If Kneale is underrated, largely neglected by the cultural establishment (Mark Gatiss had to argue for his recognition through his BAFTA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001), then Robert Holmes is criminally overlooked. He has a knack of taking source material and transforming it into new brilliant shapes. He is a perfect fit for ‘Doctor Who’. And after a couple of hesitant steps, he bursts onto our screens – introducing the new format for the show and the new Doctor and Liz Shaw. In the seasons ahead, he would be trusted to introduce Jo, the Master and Sarah Jane Smith and become really the go-to writer for Terrance Dicks, even surpassing his mentor Mac Hulke.

Mrs Peel you are wanted…

The feel of this story, largely courtesy of the extensive location filming and use of 16mm, is more closely matched to season 5 of ‘The Avengers’. Look at any of those restored stories from that series in ‘The Avengers Complete Collection’ set and compare them to the Blu-ray of ‘Spearhead’ – they feel of a piece. Watch ‘The Cybernauts’ (from the previous season still in black and white) and ‘Return of the Cybernauts’ for a template for the Autons – or any number of episodes where politicians or civil servants are duplicated, hypnotized or possessed. As a result, the scene of Scobie meeting his Nestene replica feels straight out of ‘The Avengers‘.

The setup also bears some superficial resemblance – Steed and Mrs Peel, the Doctor and Liz. I mean they aren’t a perfect match by any means – the relationship between the Avengers pairing is much more arch and suggestive and Mrs Peel gets an awful lot more action – Liz never really gets to fight their opponents – the run across the weir in ‘Ambassadors of Death’ is probably the most action-packed moment that she gets. She is rather an amalgam of the older, intelligent, non-nonsense female Mrs Peel and the female scientists from ‘Quatermass II’ and ‘Quatermass and the Pit’. Caroline John is 29 during season 7 and feels much more obviously a ‘woman’ rather than ‘The Doctor Who girl’ stereotype than any of the female companions since Barbara Wright. So again, even in this regard the series is taking something from another influence and transforming it into something more recognizably Who-ish. The other main character in the mix – the Brigadier becomes that trope of many a cop or spy show/film – the weary boss figure, having to deal with the idiosyncrasies of the eccentric, maverick genius, who he has to tolerate because he gets results. The nearest counterpart in ‘The Avengers’ is probably Mother – Steed’s boss in series 6, although he is a far more whimsical character than anything in season 7 of ‘Doctor Who’. Patrick Newell would of course, play the Brigadier’s temporary replacement in ‘The Android Invasion’.

Bold as a knight in white armour…

As for the new Doctor – well along with a hint of John Steed, there is also a lot of Adam Adamant in there. For example, you could just imagine Adam saying ‘unhand me Madam’ as the Doctor does in episode one of this. This Doctor is partly a man out of time – painstakingly mannered at times, but pompous, short tempered and unnecessarily rude at others. He is also a very modern creation (well contemporary for 1969/70) – a mix of eccentric scientist and boffin, man of action and adventure and lover of the good things in life. Like Steed, he appreciates a fine wine and good cheese. However, you could also imagine the new Doctor having a night out with Jimi Hendrix or Marc Bolan as much as Tubby Rowlands at the club. He is a teller of tale tales, a raconteur and bon viveur, theatrical impresario and showman. All wrapped around a scientific curiosity and a strong sense of moral authority. Like Adam, he is a very British hero, but unlike him, he is also so much more and has a unique perspective on Britain and the planet at large from his exile. He is also less likely to skewer someone with a sword stick or throw them off Blackpool Tower – the odd Ogron aside!

Patients from space and Cottage Hospitals..

The final influence I was going to cover was Robert Holmes. Yes, that’s right, by this point not only was Robert Holmes ‘re-interpreting’ the works of others, he was already plagiarizing his own work! There are some similarities with an earlier Holmes work – the low budget sci-fi film ‘Invasion’. It is unclear how much Holmes actually wrote of it – it was his storyline idea at least. A writer friend of his, who apparently the film studio asked for, is credited with the script. Anyone who thinks Terry Nation is the only old school writer to recycle or plagiarise his own work, clearly hasn’t seen much by Holmes or Brian Clements or any of those old freelancer pals.

An early scene in the film ‘Invasion’ with soldiers in a radar truck tracking a UFO is almost word for word ‘Quatermass II’, even closer than the opening of ‘Spearhead’. Interestingly, although he didn’t write the film screenplay – Holmes provided the storyline, the hospital setting and medical aspect of ‘Spearhead’ obviously comes via this film. If Holmes didn’t ever see ‘Quatermass II’ as he claims, maybe the credited writer of ‘Invasion’, Roger Marshall did? One other scene in this film is particularly close to the conversation Henderson and Lomax have in ‘Spearhead’ – an examination of the x-rays and blood taken from the ‘patient from space’. The storyline for the film was conceived by Holmes in conjunction with Dr Phyllis Spreadbury, who was the medical advisor working with Bob on the TV series ‘Emergency Ward 10’. Apparently, they often discussed sci-fi plots whilst working together and so the film is very much based around the hospital and treatment of the ‘man from space’ because of this. All if this makes its way into ‘Spearhead’ via ‘Invasion’. Just as Holmes’ former profession of a journalist does in the scenes set around the arrival of the Brigadier and Liz at the cottage hospital.

So, Holmes gathered together ‘Spearhead’ from a cocktail of influences and aspects of his own life and people he worked with, some direct some possibly second hand. In the next part, I will discuss why ‘Spearhead from Space’ is also wildly original and influential despite all of this!

Plastic crap, a binary cardio-vascular system and hospital clothes – the legacy of ‘Spearhead from Space‘

Despite all of those influences analyzed in the previous article, ‘Spearhead from Space’ is also massively original and imaginative. Why? Well because, like ‘The Plastic Eaters’ episode of Doomwatch (shown in 1970 – months after ‘Spearhead’ aired), it takes a modern innovation (plastic) which is suddenly all pervasive in contemporary life and it turns into a source of horror. More than that, it forsees a point when plastic crap (plastic daffodils and troll dolls etc.) will become a major issue for the species on our planet. ‘The Plastic Eaters’ is very prescient in that it involves a virus which has been engineered to break down plastic waste escaping in the wider world. In that world, dealing with plastic waste unleashes a major issue for society as airplanes fall apart in mid air and the all pervasive nature of plastic in the fabric of our lives becomes a weakness.

People (certainly in the UK) seem to act as if ‘Blue Planet II’ was the first time we’d heard of plastic in the biosphere being an issue – it really isn’t, not by a long way. You have these shows (add in ‘The Green Death’) in the 1970’s that highlight the issue of its non-biodegradable and potentially toxic properties. We just chose to ignore the issue. 15 years ago, I remember travelling in rural India – where every village had a mound of plastic waste on the outskirts, bound never to decay and always growing. Or Midway Island where Laysan albatross chicks were dying stuffed full of plastic crap – toothbrushes, small toys, cigarette lighters – a growing issue closer to home in our seabird islands, amongst for example Gannet colonies. I have photographs that I took of Sperm Whale calves playing with plastic in their mouths in the Azores and a Leatherback Turtle entangled in plastic netting and fishing gear from the Bay of Biscay. Even the beaches I have walked in the High Arctic are far from immune to this issue. A recent Big Finish Torchwood play ‘Sargasso’, explored this very issue of plastic waste at sea via the Nestenes with horrific consequences, all using the toolbox provided by Holmes all of those years ago. Honestly, if we regard Nigel Kneale and Kit Pedler as prophets of the future or even someone like Charlie Brooker now – then I would add Robert Holmes to that list. We are all after all heading towards the world of ‘The Sunmakers’ and our history is becoming as maleable as that of the Time Lords in ‘Deadly Assassin’ or ‘The Mysterious Planet’, truth a precious commodity.

‘Spearhead from Space’ is also hugely influential on the future of ‘Doctor Who’. I will cover the sequel ‘Terror of the Autons’ later, but whilst I don’t entirely subscribe to the view that it is a mere retread of ‘Spearhead’, it obviously revisits some of the core features of the Nestenes and Autons established in the original. Holmes was himself reluctant to revisit the Autons/Nestenes – but he was a freelance writer and Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks were keen – so he reworks the story into the new format of season 8 and uses this framework to introduce three new regular characters – The Master, Jo Grant and Mike Yates. Something that Russell T Davies uses again when having to introduce the new Doctor, Rose, Mickey and Jackie to a whole new audience. It seems that familiarity of the Autons earmarks them as a useful, easily understood threat, that can be simply and economically explained to a new audience, whilst concentrating on introducing new regulars or formats. It does however mean, that opportunities to properly explore their nature are somewhat spurned in favour of set-piece action/horror sequences.

“Spearhead‘ also introduces some of the conventions of regeneration and the anatomy of Time Lords that will become a mainstay up to this day. It is hard to remember just how little ‘Power of the Daleks’ tells us about the process that the Doctor has undergone and how different it is in many ways to the other regenerations after ‘Spearhead’. This story introduces the Doctor’s two hearts for example, that his blood and physiognomy is different to humans. The very hospital setting has also become something of a ‘Doctor Who’ regeneration story tradition. It is used in ‘The TV Movie’ as McCoy’s Doctor ‘dies’ on the operating table and McGann comes to life in the morgue.

Even the simple act of the Doctor ‘choosing’ his costume is a departure – Troughton’s Doctor clothes apparently changed with him – here the new Doctor is first seen wearing the old Doctor’s costume – several sizes too small. The new person choosing and putting on new clothes is almost a rite of passage – a signifier that the process is complete and the new Doctor has come of age and is ready to take on the mantle proper. This convention again is used in the ‘TV Movie’ with the McGann Doctor choosing a Wild Bill Hickock fancy dress costume in the process. Many years later again, a cottage hospital is the setting for Matt’s Doctor to face up to Prisoner Zero and the Atraxi. For the denouement choosing his new outfit as Amy looks on and Rory hides his eyes to spare his blushes. Matts’ nakedness mirroring Pertwee’s in the ‘Spearhead’ Shower sequence! Aspects even make it into ‘The Christmas Invasion’ – with the Doctor similarly sidelined in his sick bed as the menace spreads only to breeze in to solve the issue in the second half of the story and Jackie wondering what else he has two of! Again, we see something similar in ‘Deep Breath’, with Capaldi’s Doctor confined to bed, only to sneak off at the first opportunity.

Of course the show-piece sequence from ‘Spearhead from Space’ is repeated and expanded in ‘Rose’ – launching an entirely new era for the show, written by one of ‘Spearhead’s young viewers. Russell’s pitch being – this time we get to break the glass! Something that always makes me laugh – we hankered for such simple things Classic Doctor Who fans, we didn’t need ‘Star Wars’ – just a shop window to break… The sequence on the streets of Ealing Broadway made an indelible impression on the young Russell, that he stakes everything on it to work for an entirely new generation of fans and a wider audience. It places the show in the familiar and every day in exactly the way that Derrick Sherwin originally intended – ‘down to Earth’. And well despite the pyrotechnics and stunts, the shop window dummies themselves are probably quite cheap to make and easily realizable. Clever, effective and cheap – a ‘Doctor Who’ producers dream…