Long ago, and far away, in the reign of Queen Victoria, there lived a silver-haired old man, who had a very good idea. He had thought of a shelter for policemen, with a telephone, so that anybody who was in trouble could call for help. And that was clever; because nobody knew what a telephone was, back then. Because there had to be a lot of room inside the shelter; the old man invented a way to make a lot of space fit into it. Because the shelter had to be able to chase criminals, he made it so it could disappear and then appear again somewhere else.

The old man was very clever; but very lonely, and so, before he told anybody else about his invention, he used it to go exploring. He visited another world, a place called Gallifrey. There, he found a tribe of very primitive people.

The tribe of Gallifrey thought that the inventor was a god, and started to worship him, but then he told them not to. ‘I have brought new ideas for you,’ he said. ‘I want to help you.’

And so he told them about travelling through time and space, and about the police.

He taught them how to build police boxes, and he taught them about law and books and civilization.

The Gallifreyans eventually made a wonderful world for themselves, with towers and cities, lords and ladies. The inventor watched over them and advised them on how best to make their world as civilized and law-abiding as the England that he’d left behind.

But as time went on, he became discontented with the place. The Gallifreyans had taken his ideas far too much to heart, and they’d become boring and stuck-in-the- mud. He invented a way for them to start another life when they died, and gave them another heart, hoping that this would make them joyful and happy. But they were just as dull, and now they lived longer. Worse than that, they no longer had children, so there was nobody noisy around the place to ask questions.

Finally, he could take no more of it. He took one of the police boxes and headed back to Earth. The Gallifreyans would chase him, he knew, because he’d broken one of the laws that he’d invented.

But he’d decided that being free was better than being in charge.’

The Old Man and the Police Box

J. Smith 1914 (or possibly Steven Moffat 1995)

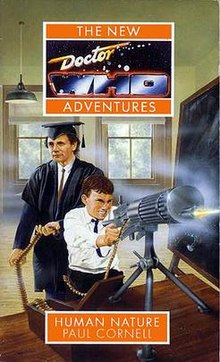

In 1995 Paul Cornell wrote his most celebrated Doctor Who novel Human Nature for the Virgin New Adventures range. It is famously a story of the Doctor taking human form and falling in love once described Doctor Who’s version of Superman II. However the novel is actually far denser and more complex than just that – featuring suffragettes and socialists, public school bullying, cricket and machine gun practice, a school boy slowly becoming a Time Lord, premonitions of the war to come, tales of owls and cats, schoolboy soldiers, the story of an inventor visiting a planet called Gallifrey and showing the inhabitants the secrets of time travel and a rather horrific shape-shifting family called the Aubertides. Human Nature is a book that if you haven’t read you might find quite surprising and in the end it is as much about the nature of the Doctor as what it is to be human his very absence illuminating the former. The book is a terrific read and to my mind a compulsory one when trying understand not just Doctor Who in the 1990’s, but also what was to happen next, when this generation would have the keys to the kingdom.

Being Human

At the start of the book, the Doctor decides to become human – we think to help him understand how his friend Benny is feeling at the loss of someone she loved (Guy de Carnac a French Knight from the previous story Sanctuary). The Doctor’s essence is stored in a biodata pod that looks like a cricket ball and his new persona, a school teacher from Aberdeen, is created from the memories of his companions by the TARDIS – including amongst others, bits of Harry Sullivan! And in his memories he has a long lost sweetheart called Verity. He becomes a teacher at Hulton College School in the village of Farringham, Norfolk in 1914 on the eve of war.

Benny is lodging in the village at a cottage owned by the local museum curator and is posing as John Smith’s niece, down from Newnham College Cambridge for the summer. Actually Benny gets some terrific stuff to do in this book, running around with Constance the local suffragette and battling to survive – she is beautifully written by her creator and still coming to terms with the loss of Guy de Carnac from the previous book. She has been left to her own devices, only knowing the location of the pod (in a tree in nearby woods) and a list of things the Doctor should avoid doing:

Things Not To Let Me Do

1: Commit suicide, if for some reason I want to.

2: Do physical harm to anyone, if you’re aware of it.

3: Eat meat, if you can.

4: Eat pears. I hate pears, I don’t want to wake up and taste that.

5: Leave the area, or you, behind.

6: Get involved in big sociopolitical events.

7: Hurt animals, especially owls.

8: Develop an addiction.

9: Anything impossible.

There is something missing from that list 10. Fall in love

A Love Supreme

‘Well, perhaps you and I could play a hand or two tomorrow evening. Would you like me to cook?’

‘Yes.’ Smith, still failing to open his door, turned and gave her a shy smile. ‘That would be good.’

‘Is there anything you don’t like?’

‘Burnt toast.’

The great joy of the love that John Smith finds in Joan Redfern – a science teacher at the school is that it isn’t some youthful story of desire, although it has elements of that in it, but rather that it is love found when least expected between two middle-aged lonely people. That is something that isn’t very often depicted in our culture, but works extremely well here and is rather sweet and quite touching, despite Benny’s reservations about Joan. He isn’t young and dashing, but rather bumbling, an oddity, rather sweet and funny, not really understanding social conventions and the rules of life in the British Empire. She isn’t young and naïve, but just lonely after the death of her first husband in the Boer War. We get an echo of this when she later touches the biodata pod and her thoughts on how he Doctor differs from John Smith:

Joan took the Pod in her hand. ‘Don’t worry, I won’t run away with it.’ She felt it react, in some odd way, to the new touch. Then she closed her fist round it and closed her eyes. ‘Arthur,’ she whispered. ‘Oh my God, Arthur.’ Then, with a cry, she let go of it.

The Pod fell to the ground. Joan took a step back from it. ‘I saw Arthur, my husband, as he died. And then I felt the Doctor in the sphere. His opinion of it. He was so distant, so… cold. It was as if he was watching that death in my mind, but from such a height. Oh, John, I’m afraid of him, I’m so afraid of him.’

We get to see their first moments as lovers and see their contentment together, as they play chess or go for a picnic. A normal life together. For a while though, before life intervenes in a myriad of horrific ways, we also get the sheer joy of the Doctor happy in love. One of my favourite passages is as he leaves Joan that first evening:

Smith skipped down the lane, his hands in his pockets, whistling a tune that the Isley Brothers hadn’t written yet, a grin that was unwipeable spread across his face.

Up ahead, he glimpsed a street lamp that hadn’t ignited, the last one on the comer before the darkness of the countryside swept in.

He looked up at it and raised a hand, intending to tap the pole.In romantic stories, the gas filament would then ignite. He tapped.

Nothing happened.

Still indomitable, he shrugged, turned and made his way off down the lane. Behind him, a little corner of light sprang up. He glanced back at it and nodded.

‘Yes.‘

Good and Bad at Games (all of that rugby puts hair on our chest, what can you do against a tie and a crest?)

‘I’ve seen the future,’ he whispered. ‘And everybody dies. ‘

So, I have no idea what goes on at public schools, everything I know about that world comes from TV, films or books. I went to a comprehensive in Merseyside, I say that not as some badge of honour, but just to give some perspective that I am clueless as how to realistic any of the depictions I have seen of how the houses and dorms work, the bullying and the fag system actually are. If we did something wrong we got caned by the headmaster, here it seems that is prerogative of the head of house – an older boy, in this case the horrible, racist, reactionary Hutchinson. There are unwritten rules for boys and masters alike, all based on hierarchy and institutionalized bullying and violence a preparation for empire. All of which John Smith – in an echo of the Doctor rather sweetly subverts almost by accident:

‘Missing one’s name in a roll call is a disciplinary offence, sir, under the rules of the school. Aren’t you going to do anything about it?’

‘Why, what do you think I should do?’

‘The standard punishment is ten strokes of the slipper, sir. Perhaps you weren’t aware of it.’

‘Aware?’ Smith looked uneasily round the class. ‘Yes, I knew that. But this is my form room. Can’t I change the rules?’

‘None of us can change the rules, sir. Even if we’d like to. If you’d prefer it, I could administer the punishment myself.’

Smith fiddled with the air, thinking. ‘Yes,’ he decided. Timothy opened his mouth in horror. Last time Hutchinson had punished him, he hadn’t been able to sit down for three days, and couldn’t get to sleep for the pain of the bruises.

Hutchinson stood up. ‘May I have the slipper, sir?’

Smith was fumbling inside his briefcase. ‘I wondered why I had to bring one of these to every lesson. I nearly wore it, but I’d have ended up walking in circles.

Ah!’ With a flourish, he pulled a fluffy pink slipper from the bag, and experimentally slapped it across the back of his hand. ‘Yes… that shouldn’t hurt.’

He looked up at Hutchinson. ‘Ready?’

Hutchinson had walked up to the desk. Now he stopped, stiffly turned and headed back to his place. ‘I think we can defer the punishment, sir.’

Fitting in, playing the game, understanding those un-written laws is everything. Even in his human form, John Smith, the Doctor doesn’t fit in. He is called to the Headmaster for a pep talk, adored by the younger boys but despised by the likes of Hutchinson.

Bullying at school is a real theme of Paul Cornell’s books. It appears in his first book Timewyrm:Revelation, where Ace is confronted again with her school bully Chad Boyle. His latest novel Chalk also concerns bullying in the 1970’s in Wiltshire. It sometimes makes for difficult reading, to see Paul exorcising demons in print – he must have really hated school. The bullying here almost ends in Lord of the Flies territory – Timothy Dean being hung out of an open window, the other boys leave him for dead in his bed, until the morning. In the end only the possession of the biodata pod saves him from death – giving him a Time Lord respiratory bypass system. How else can we read this but a schoolboy wishing to be saved from the pain and anguish of bullying by becoming the Doctor surviving and going on to win.

How many Doctor Who fans have been bullied at school for not quite fitting in, being different, being a swot? Have many not been? Maybe the more recent generations of fans are spared this – I hope so. How many of those bullied knew that they were cleverer than the bullies and there is a better way to win? Paul has talked about this in interviews, but you hear a similar story from other fans – Toby Hadoke for example tells a story of using the quote, ‘you’re a classic example of the inverse ratio between the size of the mouth and the size of the brain‘, to a bully who has chased him and his other Doctor Who fan friend. Timothy isn’t completely alone – there is another outsider – Anand or ‘Darkie Unpronounceable’, the son of a ruler of a minor Indian state is his only friend – two outsiders. This is one of a number of references to imperialist racist attitudes in the book.

Later Paul exacts his revenge on all of this – he turns this school to glass as the Aubertides detonate a fusion bomb and disposes of schoolboys and masters in some really horrific ways.

A tiny metal sphere was imbedded in the back of his scalp. The boy turned back to Smith. ‘What is it, sir?’ Smith stared. I don’t – ‘ Phipps’ face turned red. His lip started to vibrate, as if he was going to burst out crying. ‘I’m sorry – ‘ he blurted out.

And then his head exploded.

The blood slapped Smith straight in the face, covering his chest and hands, a fine spray filling the whole room.

The boys yelled and screamed, falling to the ground. Smith stumbled forward, blinded by the liquid, trying to find Phipps’ body.

Above their heads stood the school. Only now it was made of fused glass. Patterns of light from the shimmering cloud scattered through it, rain bowing the gym and the library and the kitchens. Multiple lenses twisted the images and magnified them, the fiery brightness flickering through the Upper School and along the dormitories.

Inside the building there were glass statues, boys captured as they were caught in postures of running or hiding, their bones burst into glass and their flesh fused away.

In the silence, silver dust began to fall.

The Times they are a Changin

Another clever feature of the book is the setting. The year 1914, the world on the brink of war that is mined here very successfully – the premonitions that Timothy Dean has of the deaths of the schoolboys and then especially in the epilogue. There are also references to the Boer War and the sort of bullets that one might use on natives rather than Europeans. Rocastle, the Headmaster, so keen to sacrifice himself for the cause of King and Country represents both the volunteers so keen to join up later in the year, but as an authority figure and one educating the young schoolboys and in particular the OTC, he also represents those responsible for sending so many to the war and to their deaths. We see a premonition of that here as he leads the boys into battle against the Aubertides. Rocastle represents authority, empire and the past, something the war would start to change although I suspect that there are still plenty like him out there, in the cabinet for instance.

There is also change of a more positive sort – referenced by tomorrow’s man socialist Richard Hadelman, the local Labour candidate. Later he is revealed to be the gay partner of Alexander Shuttleworth the museum curator, who has carefully fostered an image as a womaniser and advocate of free love to cover himself. More especially though change is represented through the suffragette movement and the character of Constance Harding who alternates between hunger striking in prison and being released to feed herself up. When she first meets Benny in the Lyons Tea House, only Benny will allow her to sit on her table – much to the annoyance of the other customers. She is used to a life on the run and has access to explosives. In the end her fate is really rather horrible and very sad.

We are family

The Aubertides – August, Hoff, Greeneye, Serif and Asphasia are an interesting lot. They are a family, rather than a species (similar to The Slitheen in that respect, although totally different in execution). I am guessing that they are maybe more influenced by comics than the usual Doctor Who villains – I can see them in a comic strip far more than on TV, so isn’t that surprising that this is an aspect that was changed to some extent in the TV version. There is variation in them and they each have slightly different specialised talents, but there are maybe just too many of them. Certainly for me, whilst reading this again I kept forgetting who they all were. The exception is probably Asphasia – a little girl with a deadly balloon that is actually part of her. The Aubertides want Time Lord biodata to allow them to regenerate, since they reproduce asexually and within strict limits, regeneration would allow them to reproduce exponentially. During the book they commit some really horrific and quite shocking acts – both against individuals (everything from murder, eating their victims, to the threat of rape) and en masse (the destruction of the school, the biological attack on the hospital etc.). Paul Cornell doesn’t pull his punches here -a theme running through each of the books I have covered, even ‘Nightshade‘ is far more horrific than the TV series ever could be. We even get to see via the biodata pod what the Aubertides will do if they succeed. We see them and their many children invade Gallifrey and the executions of Flavia and Romana.

Never cruel or cowardly

Paul Cornell writes brilliantly on the nature of the Doctor – borrowing ‘never cruel or cowardly‘ from Terrance Dicks re-issue of ‘The Making of Doctor Who’, a description or mantra that would later be re-purposed in the show’s 50th year by Steven Moffat in ‘The Day of the Doctor’. Very cleverly the absence of the Doctor illuminates the nature of the Doctor, just as Smith shows us what it is like to be human. It is also raises the stakes in the story, as Benny and the villagers battle just to survive. We get something similar in the TV series ‘The Christmas Invasion‘ for example or ‘Turn Left‘, when we see what a universe without the Doctor is like. The absence of the Doctor for much of the story shows us what we are missing – he might be far from perfect in this incarnation, but we need him and without him things start to spiral out of control. Despite that, rather like the presence of the Third Doctor in season 8, his presence here and decision to become human causes the Aubertides to be in Farringham in the first place and thus indirectly causes the destruction of the lives of so many innocents, but nevertheless, the point still stands.

We also get glimpses of the nature of the Doctor the voyage of change and discovery that Timothy Dean goes on – also starting to become the Doctor. Is it reading too much into this to read it as the young fan becoming a better person as they grow up through their exposure to ‘Doctor Who’?

In the end, the defeat of the Aubertides is very neatly done – the Doctor takes back his Time Lord biodata and John Smith’s humanity is absorbed into the pod. When August takes the biodata pod from the Doctor, he absorbs John Smith and so ultimately John Smith gives himself up so that the Doctor can save the day and Joan, then defeats the Aubertides. This very neat switch gives us something that the TV version does not – it effectively allows The Doctor and John Smith to meet and for Smith to comment on the nature of The Doctor.

.. he believes in good and fights evil. That, with violence all around him, he’s a man of peace. That he’s never cruel, or cowardly. That he is a hero.’

Smith closed his eyes for a moment. ‘It felt good to hear it confirmed. Of course, that’s not a definition of me. That’s you, Doctor.’

The Doctor reached out and touched him on the shoulder. ‘As I believe you said, being me is a state of mind. Six other people apart from you and I have had a go. You were rather good at it.’

That last line for me is echoed in Jackson Lake in The Next Doctor, another human being touched by memories of the Doctor.

Goodbye to all that

Also beautifully written are the scenes in the aftermath of the devastation, where the Doctor visits Joan to say farewell and also in a way says farewell to being human. He is leaving love behind to go back out into the universe and fight his battles.

‘Could you not become John Smith again?’

‘If I could find another Pod. But such horror followed me. Such – ‘ He dropped his head. ‘That’s not true. I might become a man again, but it wouldn’t be John. And I wouldn’t want to do it. I know everything I am, and that includes the knowledge that I want to be me.’

‘Well…’ Joan let go of his hands, and moved off a little way. ‘I believe that you’re a good man. You didn’t know that your human self would fall in love.’

‘It seems obvious now. What else do humans do?’

‘Go to war.’

‘I did both, then. And I was half successful.’

He paused for a moment at the door and gazed at her face. ‘I hope that one day, when I’m old, when my travels are over, and history has no more need of me, then I can be just a man again. And then, perhaps I’ll find those things in me that I’d need to love, also. Not love like I do, a big love for big things, but that more dangerous love. The one that makes and kills human beings.’ He stretched out a finger to touch her face, but suspended it, an inch from her skin. ‘It’s a dream I have.’

He turned away and walked down the road.

He didn’t look back.

That is rather lovely and hints of the sadness of The Doctor – everything he has given up to wander the universe and fight oppression and injustice. Later in the TARDIS console room, Wolsey – the cat that Joan has given him, observes him:

‘The cat could see that the man was weeping… But there was nobody he could tell.‘

So maybe being human for a while has shown the Doctor what human love, loss and grief is like after all?

The Epilogue

If that ending wasn’t emotional enough when get the really rather beautiful epilogue. This follows the Norfolk Regiment in the Somme in July 1916 including Richard Hadelman (comforting himself by singing The Red Flag to himself as he thinks he is about to die), Lieutenant Hutchinson and Timothy Dean now working for the Red Cross, having refused to fight. As the fateful bomb falls during an attack and claims Hutchinson’s life, Hadelman survives – Dean carrying him back to his own lines and safety. And then it cuts to the present day, in a very moving passage where we see the impact the Doctor has had on Timothy Dean:

The bells of Norwich Cathedral rang clear and sharp on an April morning in 1995. Snowflakes were falling steadily. Above the cathedral blew great billows of them, whipping around the comers of the dark building as if to emphasize the structure’s harsh lines.

From out of the building trooped a handful of very old men in uniform, supported by their relatives and children. The Norfolks who’d fought in the Great War had a yearly reunion in the city, though their numbers grew smaller every time. This might well be the last one.

By the door of the cathedral, at some distance from the marching men, another old man sat in a wheelchair, surrounded by his family.

‘I’m going to be just like you,’ the girl told him.

‘Then you’ll never kill anybody, even when everyone else is?’

‘Never.’ The girl was looking up at him, hushed, as if she was receiving a benediction.

‘And you will never be cruel or cowardly?’

‘Never.’

And Timothy lay his head back against his grandson’s hand, his cheek warm against the man’s skin. He breathed deeply, and fell into what would turn out to be his final sleep.

The white poppy had fallen from his lapel in his exertions, and was left, unnoticed, on the pavement as the Dean family went on their way. Just before they turned the corner, the little girl looked over her shoulder and saw the Doctor bending down to pick the poppy up. She looked at him curiously and he gave her a smile.

Then she was gone. The Doctor slipped the white poppy into his buttonhole. ‘So, where do you want to go?’ he asked Bernice, who was shivering in her dufflecoat.

‘Somewhere that sells hot chocolate and crumpets.’

‘After that.’

‘Perhaps we could go and do something good. Help somebody.’

‘We could go back to Guy.’

‘We could go back to Joan.’They looked at each other, and they might have looked sad. But instead they smiled.

The two friends wandered off into the city to find tea and crumpets and warmth.

And somewhere in the sky overhead, for an instant before they dissolved into mist, two snowflakes were the same.

Long ago in an English spring.’