‘So, he called it Heaven in Common Tongue, which meant that the translation fitted with whatever your own particular vision of bliss was. The High Command hadn’t liked that much. They hadn’t liked it either when Hall, once the Dragon Wars had ended and the two species were united against the Daleks, walked into the Draconian Embassy and told the Ambassador about Heaven too.

The Ambassador was old Ishkavaarr, the Great Peacemaker, Pride of a Thousand Eggs. He and the President of Earth were working on a deal then, as they always were, and Ishkavaarr was worrying about it. One night, he woke from a dream, because Dragons do dream, and realised what the missing element was.

He called Madam President in the middle of the night, actually woke her up, and, laughing in his hissing Draconian way, told her that he knew what they both could do.

The key was a world called Heaven.

Heaven was to be the Edge Of Empire, the Peacemaker explained, a place that both sides would love to be able to visit, but neither really needed very much. It had no mineral wealth, no actual tactical value. Not even the Daleks would want it. It was, simply, beautiful. What if the two great powers were to take joint possession, declare Heaven an open world, and use the place to bury their dead?

The President was amused.

Years later, during a lull in the fighting, the leaders of the two powers met one glistening summer morning on Heaven. The grass was blowing lightly in the warm breeze, and small herbivores were gently chewing the cud. The Emperor and President signed several agreements, she wearing the ceremonial robes of an Honorary Prince. Members of their entourages sighed and sneaked off to lie in the sun and fall in love. War made any calm planet into Heaven, but this one seemed suitable for the name.

Before he died, Ishkavaarr wrote: ‘If I may be allowed to be a prophet, I believe that Heaven was given to both our peoples deliberately. There is a purpose in the giving, and a purpose that we may not discover for many years. I believe that purpose is a good and just one.’

In a typically Draconian manner, Ishkavaarr was both right and very wrong.’

Just Like heaven

Heaven is a paradise world at the edge of human and Draconian space, shared between the 2 empires. It is also where they both bury their dead in the on-going war with the Daleks. Capsules containing the dead are fired through the atmosphere from space, landing in designated areas, which are deep with the bones of the dead. The former Heavenites are long gone – seemingly leaving no trace of themselves or what they looked like, except one of their old buildings which is being excavated by a team of archaeologists. Whilst in the markets of Heaven, Draconian merchants mix with IMC security, students, travellers and the Church of the Vacuum (a death-cult that Ace describes as ‘goths’). At the library the ‘Papers of Felescar’ – a book that the Doctor is looking for has disappeared. Ace – who is still travelling with him and has just returned from visiting the funeral of her friend Julian back in Perivale, has fallen in with a group travellers.

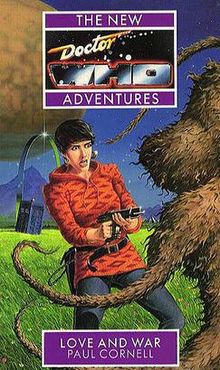

Apart from being beautifully written, Love and War manages a very neat trick – it feels like something completely new, whilst being based on a line from a Fourth Doctor story and set in a world built by Mac Hulke in Third Doctor stories, there are humans and Draconians, Daleks, ‘Earth Reptiles’, even Absalom Daak gets a mention! Beyond that though it feels like an entirely new type of Doctor Who for the 1990’s – references to contemporary 90’s indie music, TV, virtual reality and counter culture. We have teenage angst and love and sex and alcohol and death, alongside Time Lord legends and body horror. It is all very ‘New Adventures’ and its influence is still being felt in TV Doctor Who today.

Only one way to live your life

If you are looking for Doctor Who in 1990’s and what it looks, feels and smells like, for my money that is ‘Love and War’ – it is so 90’s it hurts. And that is the thing about contemporary references, some things still work in time and some things like a single from a band that you inexplicably liked just long enough to buy it, before relegating to the dark places of the inside, just doesn’t. I might not understand the New Adventures in the nth degree of detail, but this is my time – I understand it. The music, TV, comedy, it’s tribes and what was happening culturally and politically to British society. So here we have rather brilliant references to the music that I love – ‘My Bloody Valentine’ (‘the noise of death. Like My Bloody Valentine turned up to eleven’ ) as Ace enters ‘puterspace’ (I’ll explain later), references to Teenage Fanclub, Higher than the Sun and a trickster who bears a very strong resemblance to ‘Big Night Out’ era Vic Reeves (‘measuring field mice with an industrial micrometer’, ‘But you couldn’t, could you? You wouldn’t let it lie’). Others, Ace having a ‘Kingmaker’ t-shirt don’t really work now (maybe the others don’t, I can’t judge), if they ever did – were they ever liked? Come on own up – who liked them? How many of you have a tape or single or cd tucked away somewhere?

Another aspect that fits in with this time period perfectly is the depiction of the travellers – or as Ace calls them ‘Crusties in Space’. Despite not being my scene (The Levellers, New Model Army etc.), it is a time I do remember well. In 1994 I moved from the North West of England, heading south where there was work. I ended up in a Cotswolds market town, which was just a bit of a change from Liverpool and Manchester. My nearest cities were (still are) Bristol and Bath and in the early to mid 90’s, when Paul was writing ‘Love and War’, ‘crusties’ or ‘New Age travellers’ were seen all across the west of England – dreadlocked, with dogs on string in the city centres, on the streets, at festivals and protesting at the road builds at Twyford Down in the early 90’s through to the Newbury Bypass in ‘96. One even became famous – an environmental hero in fact – Swampy. They lost the battles, but in the end won the war as the incoming Labour government cancelled most of the other road schemes.

The movement was an odd hybrid of hippy, folkie and punk with a bit of gypsy culture thrown in, not unlike the ‘Planet People’ in Quatermass. Here they are depicted as slightly the wrong side of the law, busking, a bit of thieving, heading out into the stars in convoy, often arriving on new planets before colonists, but also caring, loving and operating an anarchist community – they are the heroes of this book. There is an Irish connection through their names – Roisa, Maire, Cathlan – but the main protagonists are Jan and Christopher. Those two took part in a military drugs trial instead of going to the Dalek War – Jan gained pyro-kinetic abilities and Christopher became sexless, but possessed of mental powers. Jan is good looking, a bit cocky and yes you’ve guessed it Ace’s love-interest this week.

The other very 90’s connection is puterspace – a virtual reality world. The travellers share this space with IMC and the military, but have fashioned their own ‘celtic’ world of the ‘The land under the hills’ and ‘The Great Wheel’ within the virtual reality and have their own avatars. So bear in mind that the internet and AOL where just really starting in 1992, gaming was on the rise and moving out of arcades and IBM’s PS2 PC was only 5 years old when this was written. Computer technology was changing rapidly, but was not yet entirely commonplace in the home or workplace. Fiction was exploring this change, in particular virtual reality worlds where all the rage after William Gibson’s ‘Neuromancer’ in 1984, cyber punk and the movement that would end up with the more populist expression of this – ‘The Matrix’ at then end of the 90’s. Doctor Who had been there before – with its own virtual reality world – the Matrix in 1976, explored again in Trial of the Time Lord in the mid 80’s. It is unthinkable that if the show had carried on into the 90’s on TV that this area wouldn’t have been explored further as well.

Archaeology, time travel, beer and diaries

This is a book about endings and new beginnings as well and introduces a new companion for the Doctor. Before there was River Song, there was Professor Bernice Summerfield, time travelling archaeologist with a diary. Superficially they sound similar, but really they are quite different. Benny is introduced here and is instantly recognisable and well just really well drawn – probably the most full realised companion introduction since Time Warrior and a really skilful exercise in writing for female characters. I now have difficultly thinking about her without hearing Lisa Bowerman’s voice, a very astute bit of casting. After Ace, a slightly more mature (around 30) female character works very well, she has a bit of a tragic past – a legacy of the Dalek Wars, but that isn’t over-played and she is good fun to be with, clever, funny and likes a drink or two. She is more relatable than River – she has self-doubt, less self-confidence in affairs of the heart, suffers from hangovers and is, well more human than River. Through her diary (pre-dating Bridget Jones) we are privy to her innermost thoughts, a device that works very well – actually I think that would work well in the TV series too. She also brings an interesting new perspective on the Seventh Doctor – less of a mentor/pupil relationship and more equal, her maturity working very well with him.

‘The silent gas dirigibles of the Hoothi’

The quote above is from ‘Brain of Morbius’ and refers to the stealthy spherical, gas-filled ships that the Hoothi travel in that are able to avoid detection. I always love that – how a single line in a story, mentioning a species that is never seen or even heard from again, can 20 years later inspire a fan to write something like this book. Here, the Hoothi are a group fungal species that feed on the dead, absorbing them physically and also mentally – old enemies of the Time Lords, who disappeared long ago. Their ship – the spherical ‘silent gas dirigible’ is made of the skin and bone of their victims, full of fungal growth, semi-absorbed creatures and the foul gases produced by putrefaction. Heaven is a trap that they have set – the Humans and Draconians conned into making Heaven a place to bury their dead. This is all food for the Hoothi, who had been harvesting the original Heavenites for years. On Heaven, they have been nurtured by Phaedrus and the Church of Vacuum – a sort of existential death cult. They drift as worm-like spores or filaments, which are then absorbed into their victims, awaiting activation. When they do activate it is quite horrific, rather than the gradual, creeping body horror of Ark in Space or Seeds of Doom – their victims explode instantly into a mass of fungal tendrils.

‘Ace stared, horrified. On the centre of the man’s chest there was a grey patch of fungus.

And then, suddenly, it spread. One second, Trench had a human face, limbs, hair –And then something inside the old man exploded.Tentacles burst from his fingertips, his head blasted open into a mass of thrashing fungal filaments. The thing roared, an ear-splitting shriek of bloodlust. It sprang straight for the Doctor’s eyes.’

Paul Cornell’s writing here reminds me of Russell T Davies’, in that it is utterly fearless and cruel in who it dispatches and how. The book lovingly builds up the characters and relationships between the characters – Jan and Christopher, Roisa and Maire – but truly terrible, horrifying, nasty things happen to all of them. The ending is truly horrific as the Hoothi activate their victims and the dead rise up animated on the fields of Heaven to convert and absorb the living. The travellers embark on a desperate mission in a shuttle craft to destroy the Hoothi ship, but in process all of them are converted to Hoothi, in front of Ace’s eyes her lover Jan explodes into the fungal form of a Hoothi, as she is ejected in an escape pod.

‘He reached across to the ignition switch. Something roared. Cathlan was a raging mass of tentacles, struggling to get out of the escape pod. Remains of his jacket clung to the creature as it shot out filaments, grabbing bits of the hold to pull itself up. Fiona was shivering, staring at her hands in amazement. Before the shivers reached a critical pitch, she hit a control, and the window of the pod slammed shut, locking her inside. A second later, the pod was full of grey matter. Patrick leapt up, and his head exploded in a puff of fungus.

The creature turned to Jan, who was staring at the chaos that was happening all around him. His finger hovered over the button.His other hand was scratching his neck. With an effort, he seemed to steady himself, and looked through the telescope. The creature that had been Patrick stood, and watched him look. A great gasp came from Jan’s lips. ‘So that’s it!’ He laughed, biting his lip, and looked straight at Ace. She had been watching the creatures making themselves out of human flesh, like it was a dream.

‘Can’t push the button,’ he said. ‘I love you,’ she said. ‘I love you,’ he said.

Something terrible happened. And then the door slammed shut in front of Ace. The escape pod blasted out of the ship on explosive bolts, falling away in fire. Ace fell, staring, down towards the planet Heaven. ‘

It is really powerful stuff. Even the regulars come out of all of this battered and bruised, Ace leaving the Doctor after Jan’s death, the Doctor contemplating what he has done to her and Benny wondering if joining him is the right thing to do. The ending for the Hoothi is familiar, but cleverly done. As in the Quatermass Experiment, where the knowledge of Caroon, Green and Reichenheim are all absorbed into the creature or Ark in Space with Dune and Noah, the group aspect is exploited. That group aspect ultimately is the downfall of the Hoothi – as Jan who has been absorbed makes fire (on the Doctor’s order – he is connected as well having absorbed a Hoothi spore) to destroy the Hoothi ship – which is made of skin and bone and filled with gas. Later on Heaven – Ace appeals to her friend Julian, who is also in the group collective, to destroy the last remaining Hoothi.

‘Ace was encircled by tentacles. They were pulling against her muscles as she strained forward, her boots about to slip off the floor. ‘Julian!’ she shouted. ‘Jules! Are you going to stand up against that thing?’ Ace knew that she was losing the battle, and a fierce sadness shook her. ‘There’s millions of them in there, but you’re the special one! Stand up! For God’s sake, stand up and shout against them!’

Her feet left the floor, and she felt the warm embrace of the Hoothi constrict around her.

A sharp wet tentacle slid towards her face. ‘Remember Scrane End? Remember the lights! It wasn’t a spaceship, out there where the maps stopped, it was a prison! Loads of lights and guards running about, and you were so upset, you said that if that was what was out there on the edge you didn’t want to go there, but there was something else wasn’t there?! Tell me what was there!’ The tentacle slowed, and wavered.

Ace gasped as a tentacle began, almost reluctantly, to constrict about her neck. ‘You turned the Allegro, and skidded past the prison gates, and we shot up off a side road. You were driving like a madman, because you hadn’t wanted to find that, you’d wanted to find nowhere. We raced along this little road, and bounced straight out on to the sand. A beach, the edge of a marsh that lead to the sea!’ Ace was freely weeping, shouting and not caring about dying or anything else except finishing the story. ‘You jumped out of the car, and rolled in the sand under the moon, and you shouted, you said – tell me what you said!’

The Hoothi quivered. Something strong had risen up inside it. From the horrible recesses of its mouth, a powerful voice forced its way out.

‘I said . . . we’re okay. We’ve found it! There’s something on the other side!’ The voice broke out into peals of laughter, and the Hoothi shivered. ‘Ace . . .’ The voice waited for a second, grasping for something to say. ‘Goodbye!‘

‘ ‘Bye, Jules!’ Ace whispered.

The core of the Hoothi blasted apart, strands whipping across the room and spattering on the walls. Tentacles and filaments were sent spinning, as the mucoid mass at the creature’s heart exploded. ‘

Love and war and death

So, Ace finds love with Jan and then loses him – ending the book in grief and shock. Their relationship is the sort that you have in your late teens/early 20’s – something that arrives very quickly, hurts someone else in the process, ends as quickly as it starts, is strong and passionate and most likely with someone that to quote the Buzzcocks ‘You shouldn’t’ve fallen in love with’. Most of us have been there and as such it feels more likely than her relationship with Robin in ‘Nightshade’ The book is also top and tailed by a different type of love (starting with infatuation) from her Perivale days, which she has for Julian, who is gay and her loss at his death.

We also have Christopher’s love for Jan, he gives up almost everything for him and between Roisa and Jan and Maire and Roisa. Even Benny talks of her calamitous history with love and boys and the loss of her Mother in a Dalek attack and her missing Father, who she fears she will find amongst the Hoothi. Whilst the Church of the Vaccum embrace death – welcoming it amongst the meaninglessness of life – Phaedrus meeting his mother, who’s death set him on this dark path, in Puterspace. As with Timewyrm:Revelation we also have the Doctor doing a deal with the personification of Death – I think he offers first his own life and then Jan’s in return for Ace’s in his role as ‘Time’s Champion’.

Finally, the Hoothi are more than any other creature in the series (maybe the Fendahl?) linked intimately with death. As horrific as they are, ecologically, the Hoothi are decomposers or detritivores – breaking down and recycling the dead as fungi and bacteria do on Earth. Distasteful and horrific as that seems it is a vital service, the only difference here is that Hoothi also cause the death and on Heaven are farming intelligent species for this purpose – Heavenites, Humans and Draconians alike.

The Oncoming storm

For me ‘Love and War’ is a massively influential book – not just on the New Adventures range – but also on the new series. Some of these influences are obvious – for example we have ‘The Oncoming Storm’ – the name given here to the Doctor not by the Daleks, but by the Draconians, we also get ‘Never cruel or cowardly’ from the Making of Doctor Who – a post-it note on the console to remind the Doctor that:

‘He is never cruel or cowardly. Although he is caught up in violent events, he is a man of peace. ’

Which he needs reminding of here – echoed in stories as diverse as “The Runaway Bride’ and ‘Day of the Doctor’. There is also the start of the Doctor telling us his ethos and the police box as a call for help:

Ah, then you must be interested in law and order.’ The Doctor stopped, and turned to face Bernice.

‘No,’ he said, a slow grin spreading over his features. ‘I like chaos, big explosions, rebellions, that sort of thing. Why do you ask?’ ‘Because I want to know why you go around in a police box!’

‘You know what one is?’ ‘It’s from my favourite era.’ ‘I could have changed it ages ago,’ the Doctor confided. ‘But I like the shape. And the motto. Call here for help. That’s what I do. I let little children sleep safely at night, because I’ve searched through all the shadows and chased the baddies away.

I’m what monsters have nightmares about!’

The book has a wider impact though on the grammar of the series – widening its horizons and what it is capable of covering in stories. In Benny it also gives us a very modern companion, we are privy to her thoughts and feelings and her relationship with the Doctor, which is very different from Ace. It is also a favourite story of Steven Moffat (he wrote a piece about it in DWM once) and the themes of the story do re-appear – for example in some aspects of River Song, there similarities with Death in Heaven as the dead rise up from their graves converted or even in ‘World Enough and Time’/’The Doctor Falls’. You also see it’s influence, especially on series 5 onwards in that it gives us all sorts of throwaway things – the Draconians, Earth Reptiles are all really just passing through – not alien/monster of the week – the world is wider and broader than that.

The story isn’t just about one thing, it is about a whole world and it’s place in the wider universe and what happens to the people caught up in it all. It might take its cue from TV stories such as ‘Frontier in Space’ or ‘Colony in Space’, but it broadens out from there, building a coherent world where you could be a traveller or colonist, a trader, in the military or part of a corporation – going about your life – falling in love, drinking, having sex, trying to earn a living or fighting for your life. On one level I am surprised Paul Cornell wasn’t asked to adapt it for TV by either Russell or Steven (it appears it was mooted for series 5), but I can’t really see how it could be done – the modus operandi of the Hoothi is so horrible and the body horror so strong that I am not sure how it could be done, without losing most or all of it’s power.

I was going to talk more about Paul Cornell and his recurring themes and imagery – owls, churches, love, death and resurrection and Englishness, all of which are present here – but on reflection I will leave that until a later book. I’ll leave you with the conclusion to give you a flavour of that as the Doctor and Benny release a pair of owls from Heaven at the place where Ace and Julian started this story:

‘The TARDIS door was open, where it stood atop a sandy bank. The low winds of autumn blew across the grass, and the strange inner light of the police box was a white triangle against the grey ridge. ’

‘The owls in love looked down at the two tiny figures. The woman had taken the man’s arm, and they were heading back to the TARDIS, him telling her that Scrane End wasn’t the best place on twentieth-century Earth. There was a prison here. Ah, Benny was saying, but beyond the prison there’s –

The door of the time craft closed, and a noise roared into the night, and then it was gone.

The owls circled, wingtips nearly touching. They were in love, and were making new owl poetry every moment with their flight. They would prepare a nest soon, and put eggs in it. It would never occur to them not to, even in the face of certain death, the same certainty that all life shared.

Their poetry told them that they were different to other life. It was difference, not length, that made their lives what they were. It was a good poem, and this is where it came to an end, when the owls headed inland on the warm air currents of Lincolnshire.

Beneath them, an old Allegro took a corner far too fast.

Long ago in an English autumn. ‘