Hungry. It were hungry for my soul.

There is something really rather wonderful about ‘Image of the Fendahl’, a sense of perverseness about its inception that really appeals to me. This arises from the fact that when faced with a direct order to tone down the horror and violence in the show, Robert Holmes instead decides to commission a script from his youthful protégé Chris Boucher, that is a horror film in all but name. It a horror story to the extent that Hammer could have quite easily made it and really the only thing they would have needed to have changed is the addition of a bit of gratuitous nudity on the part of the possessed Thea Ransome and a few scantily clad female locals for the coven to sacrifice. Commissioning this in 1977 is gloriously irresponsible, very Robert Holmes (sits back, lights pipe, laconically states ‘that’ll show those buggers on the 5th floor’) and whilst never really getting anywhere near to being as well made or as tense as anything in Season 14, which remember had only aired only earlier in the same year, I really rather like it. I just wish it had a little bit less of season 15 in there.

As it is, it is a rather thoughtful horror story, with a decent cast and an interesting set of characters. Albeit one that would have benefitted from the full-on season 14 treatment, a bit more money, Maloney directing, a more brooding performance from Tom, and the wooden TARDIS set – the standard one looks awful here. Chris Boucher writes Leela very well and Louise is as good as ever, but she is starting to get caught up in too many of Tom’s sometimes rather poor attempts at injecting humour at unfortunate moments. It isn’t too out of control here, but the TARDIS scenes are a bit woeful (‘TARDIS wonderful!) and it is still a fair drop off from season 14 standards. I can imagine Hinchcliffe popping his head around the corner and Tom quietly dropping the idea.

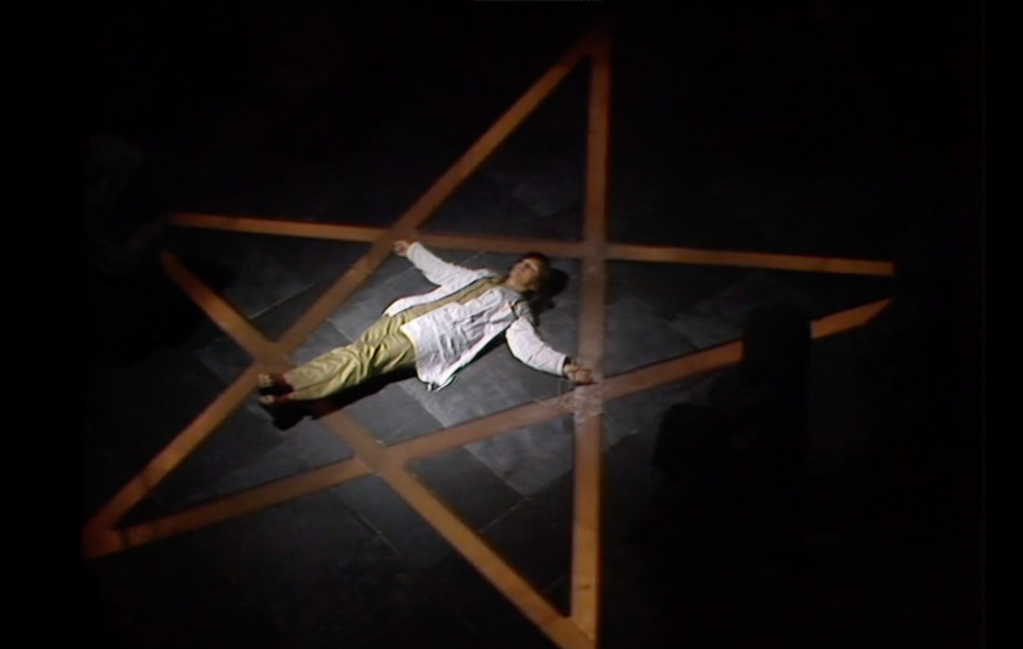

Returning to the story itself, if it is anything, it is a Nigel Kneale tribute band, it combines elements from a variety of sources, but most of them belong to Kneale. In the mix we have a combination of Kneale’s 1959 story ‘Quatermass and the Pit’ – the skulls of early hominids discovered at an archeological dig and development of humans earlier than thought. We also have elements of his tale of the exploration of a haunting by an electronics entrepreneur – Kneale’s 1972 play ‘The Stone Tape’ and the haunted wood with a fissure in time from ‘The Road’. For good measure Chris Boucher decides to throw in a dash of the more salacious – the Dennis Wheatley story ‘The Devil Rides Out’ (1968) with its black magic covens and pentagrams and adds in a monstrous gestalt creature from nightmare, that whilst a concept used for the creatures in ‘The Quatermass Experiment’ and to some degree ‘Quatermass II’, maybe owes more in execution to the work of Hp Lovecraft or in Thea transformed as the core, various other Hammer films – this aspect is pretty much a mainstay of their films.

Given all of this, I thought I would spend a bit of time and investigate the origins of the story further and that will be my next post.

“Doctor Who and the Pit’

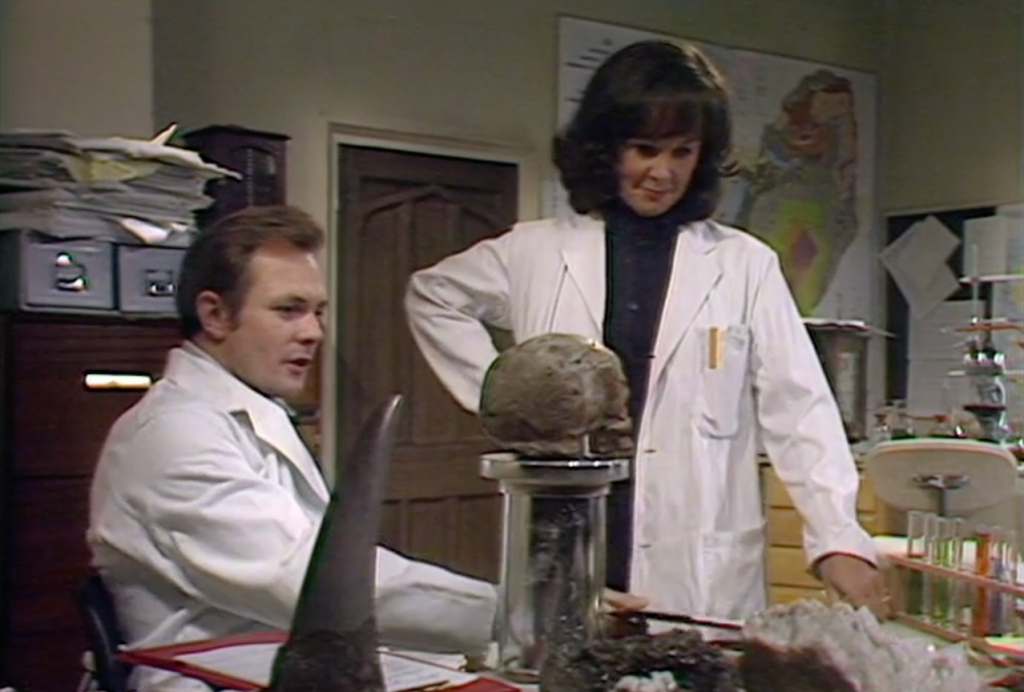

No. It is part of the bone structure itself. I believe it to be a form of neural relay, and this is where the energy is stored. It is interesting, is it not, that for as long as man can remember, the pentagram has been a symbol for mystical energy and power.

A major part of the main concepts inherent in the story come from ‘Quatermass and the Pit’. We have the ancient skeletons of a human-like creatures, buried millions of years before they should have existed. The archeologists struggling to deal with the revelation that humans are far older than previously thought possible. We also have the manipulation of the human race for the purpose of an ancient alien race, Kneale’s striking use of race memory, a location named after an ancient name for a supernatural phenomenon (Hobbs Lane/Fetch Priory), a scientific instrument that is used to see into the past and the use of the ancient magical symbols – specifically the pentagram. In ‘Quatermass and the Pit’, this is marked inside the hull of space capsule discovered in the pit, in ‘Fendahl’ is is part of the structure of the skull. That is also the difference when it comes to where the energy of the threat is stored as well – the hull of the ship glowing and throbbing in ‘The Pit’, the glowing skull in this story. ‘Fendahl‘ feels like it maybe owes more to the Hammer film of the story – which is still an excellent, cerebral piece, despite the rather lurid film poster which rather over promises on the level of flesh on display (i.e. there is none).

From ‘The Stone Tape’, ‘Fendahl’ takes much of the setting – an old haunted country house and also the main protagonists. The Kneale play features the exploration of the supernatural (a ghostly apparition of a maid servant) using modern electronic equipment and computers, by an obsessive millionaire electronics entrepreneur, a competitor to Japanese electronics companies and also the sensitive female scientist at the heart of the disturbance. In the case of the ‘The Stone Tape’ this is Jane Asher’s character, Jill – the sole female in a very male world, who he is able to see the manifestation. She is brilliant like Thea, also empathetic and intuitive, but a good deal more overwrought and far less the calm and controlled scientist. The rest of the team in ‘The Stone Tape’ have a macho laddishness about them – deliberately so it has to be said. ‘Fendahl’ is an awful lot less masculine and testosterone filled and a good deal more watchable today, but the setup is very familiar if you watch ‘The Stone Tape’ for the first time and are already familiar with ‘Image of the Fendahl’.

From ‘The Road’ – Kneale’s lost 1963 play, ‘Fendahl’ takes the time fissure in the woods. The Kneale Play is set in mediveal England but there are unearthly sounds breaking through. If you don’t know how the play develops, I will leave you to find out for yourself and is it is worth discovering unspoilered. Let us just say that the ghosts are from the future, rather than the past. The TV story is long lost, but Toby Hadoke recently adapted it for BBC Radio and it is well worth a listen if you can find it.

In ‘Image of the Fendahl’, as with each of those Kneale plays, it is the melding of the supernatural, the ancient, the trappings of folk horror, melded with modern scientific investigation – the clash of the old and the new that is key. It works very well within ‘Doctor Who’ for those very reasons – a universe in which demons do exist but are alien species, where ghosts exist but are rather temporal phenomenom – from the past or future via a time fissure. Where the trappings and rituals of the occult are explained for rational reasons – the origins of throwing salt over the shoulder, the equivalent of the use of iron at the resolution of ‘Quatermass and the Pit’. Nigel Kneale might not have wanted to admit it, but in that regard his work and the world of ‘Doctor Who’ dovetail nicely. The Doctor is every bit the rational, scientific, moral force of the Professor, just rather less of someone struggling to grasp and understand new phenomena outside of the realms of human experience and instead bringing advanced knowledge and experience and a lot more flippancy. The Professor has to formulate his own hypothesis from historical research and scientific investigation, while the Doctor already knows the story of the Fendahl and thus completely short cuts the investigative aspect of the story, making it rather ‘Junior Quatermass and the Pit’ in the final analysis although that is no bad thing to be.

In my next posts I’ll take a look at the characters inhabiting the world of ‘Image of the Fendahl’ and finally the nature of the menace itself.

The scientists, the yokels and the ‘savage’

Given that it is a story with its roots clearly showing, it perhaps isn’t that surprising that ‘Image of the Fendahl‘ sometimes feels like something Boucher wanted to write for another medium, without the Doctor and Leela. I don’t know if that ever was the case – I suspect not, but a lot of effort goes into sketching the characters in this world, such that they could stand own their own outside of ‘Doctor Who’. They did once. When I was about 12, had just read the Quatermass script books and the Target book of “Image of the Fendahl‘ was a well-thumbed favourite of mine, I re-wrote the story as a school essay! I substituted the Doctor for a professor that I’d created, not a million miles from a certain professor that Chris Boucher had replaced for the Doctor in the first place. There’s rather a neat circular trail of plagiarism. My teacher’s comment – ‘this reads an awful lot like a ‘Doctor Who’ story!’. He obviously didn’t know the works of Nigel Kneale – Kneale would have been furious!

This is the case to such an extent, that at times the two leads are slight at an angle, tangential to the main story. They take a while to arrive in it and there is a slightly odd section of episode 3, when they head off in the TARDIS to see the missing 5th planet. This is a strange diversion in the narrative, it is something that can work as a tactic – Holmes uses it to great effect in ‘Pyramids of Mars‘ and ‘The Deadly Assassin‘, but here it just feels awkward and serves really to avoid the Doctor solving the plot too early, a case where tell not show would have worked fine and it doesn’t really advance the story.

The Doctor is on somewhat variable form here and odd amalgam of Hinchcliffe and Williams era Tom, that isn’t entirely coherent. The skull scene is a good example of this – Tom’s ad-libbed ‘Would you like a jelly baby? No, I don’t suppose you would. Alas, poor skull.’ falls flat, but then in old season 12-14 style he really sells the part where he is wracked in pain, his hand ‘glued’ to the glowing skull. Where Tom does come alive, is in his scenes with Daphne Heard as Martha Tyler – rather like his similar scenes with Amelia Ducat or Amelia Rumford, Tom really does work well with and eccentric old lady! However, his scenes with Louise Jameson often aren’t always that good. There is a very uncomfortable one in particular after Leela rescues him from the glowing skull and he falls on top of her – in retrospect this looks very much like wishful thinking on Tom’s part.

Louise on her part, gamely goes along with some of his nonsense for the remainder of season 15, but it rarely works that well. Louise herself is great as usual. Chris Boucher created the character and writes her very well. One bit of nonsense I rather liked – ‘Listen. I’m sure the Doctor can help you. Oh, he’s very difficult sometimes, but he has great knowledge and gentleness’, cue Tom angrily kicking something! Also another piece that they clearly worked out in rehearsal – where he cradles her head and then runs off dropping her head to the floor, she then gives him an exasperated look. Leela does get some good moments and she clearly has a thing for Adam Colby (or from the documentary possibly Louise has a thing for Edward Arthur) – kissing him on the way out of the story. I think it is fair to say though that once ‘Horror of Fang Rock’ is out of the way, the relationship between the two leads doesn’t work as well as we’ve become used to – the 2nd and Jamie, 3rd with Jo, 4th with Sarah, that is some run.

I think one of the issues, apart from the ‘issues’ between the actors or rather with Tom, is that Tom works better on the back foot or as slight underdog, it undercuts his domineering side. In the following season with the smarter Mark I Romana where it becomes a Katherine Hepburn/Spencer Tracy relationship, the power shifting to the companion or with Romana II as a smart partner in crime or when he is paired with the somewhat saintly Sarah – where he can’t really play up as he is the new boy and he is also completely disarmed by Lis Sladen. With Leela the relationship loses its way somewhat once Holmes/Hinchcliffe have left – that idea of the Professor Higgins/Eliza Doolittle mentoring aspect is lost, in it’s place, they almost just have to work it out themselves and it starts to feel slightly dysfunctional. The nadir is ‘Invasion of Time’ in that regard, where for valid plot reasons the Doctor treats her poorly for much of the story and then she is packed off with Andred, who isn’t exactly husband potential. Louise Jameson is terrific through all of this though.

Zipped up heads and potassium argon tests

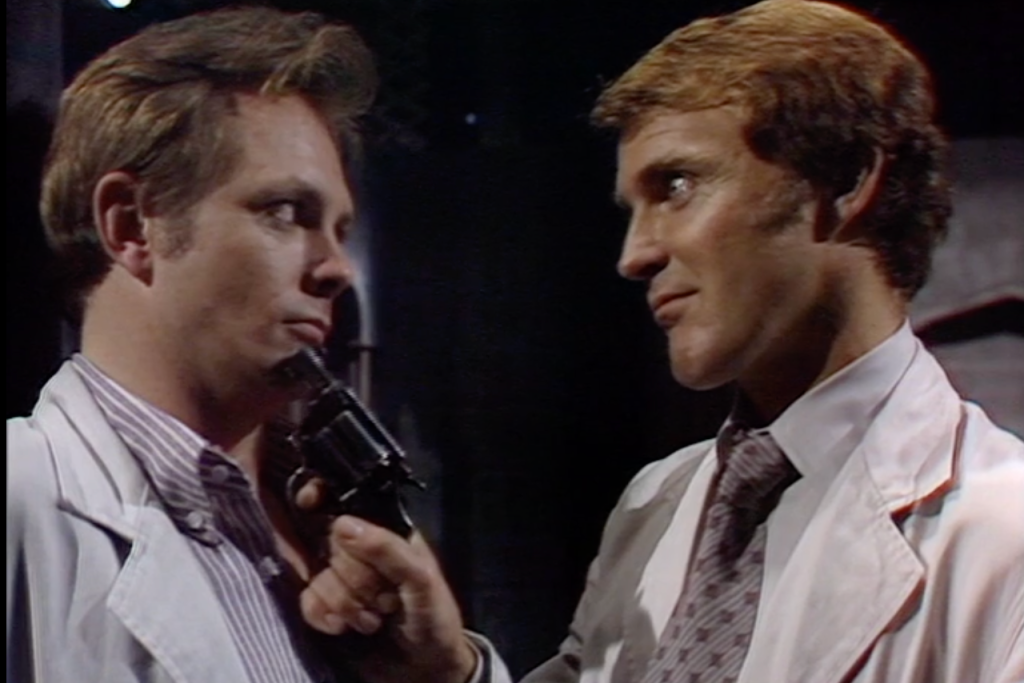

Of the scientists, in some resects Adam Colby is the most interesting – I was drawn to the idea that his rather sarcastic, cynical sense of humour might mean that he is a representation of the author Chris Boucher, in much the same way that Chris Parsons clearly is of Douglas Adams. He has a nice line in rather odd putdowns and sayings:

You must think my head zips up the back.

I accept without reservation the results of your excellent potassium-argon test.

What are you, exactly? Some sort of wandering Armageddon peddler, hmm?

In equal parts charming and irritating. He also appears to be the only character who doesn’t realise he is in a horror film! Everyone else is playing their allocated part – the doomed female scientist, the cold Germanic psychopath and the vain millionaire, duped and conned into playing his role as victim. In a non ’Doctor Who’ version of this story Colby would likely be the hero, in this, despite being a brilliant scientist he is also the voice of the audience, expressing his incredulity at what is going on.

Of the rest, Thea is rather less well drawn, although pleasingly played by the wonderful Wanda Ventham. She starts to be possessed by the skull early in episode 1 and spends the final two episodes mute as the Fendahl core – the golden femme fatale at the centre of the horror. She is taken out of character a bit too soon, unlike say Jill in ‘The Stone Tape‘ or Barbara Judd in ‘Quatermass and the Pit‘. Wanda makes the most of what she does get in this and at least makes Thea memorable.

The Doctor asked if my name was real. Fendelman. Man of the Fendahl. Don’t you see? Only for this have the generations of my fathers lived. I have been used! You are being used! Mankind has been used!

Fendelman, well you assume is gong to be the villain of the piece – it is a nice feint in the story structure which leaves him as the patsy – his whole life a fiction, manipulated into serving the Fendahl and facilitating its rebirth.

Scott Fredericks is excellent as Stael – the rather cold, teutonic scientist, who descends into Aleister Crowley occult madness. Now he is someone who really knows he is in a horror film:

THEA: Max! Max, you’re a fool.

STAEL: I shall be a god.

It is never easy to die.

A place must be left for the one who kills.

Originally Steal was going to be seen at the end, gun in hand, about to commit suicide, but for obvious reasons after the Mary Whitehouse furore in season 14, this was cut.

The relationships between the scientists are very quickly sketched in, but the script and the performances work really hard in that short time to paint in their relationships and portray them as a bunch of people who have worked together for. a while.

Country Ways

Then we have the ‘the country folk’ – Martha Tyler and her son Jack. Daphne Heard is excellent as Mother Tyler, a sort of harder version of Miss Hawthorne from ‘The Daemons‘. Her son is also nicely sketched in and has nice relationship with Leela through the story. There is also a rather nice explanation of her ‘powers’, growing up near a ‘time fissure’, later reused by Mark Gatiss for Gwyneth in ‘The Unquiet Dead’.

MARTHA: I ain’t involved in anything. I were consulted. A lot of people consult me. You know I’ve got the second sight.

DOCTOR: Yes. So you’ve lived in this cottage all your life, haven’t you, Mrs Tyler.

MARTHA: Why should I tell ‘ee ought?

DOCTOR: Well, telepathy and precognition are normal in anyone whose childhood was spent near a time fissure, like the one in the wood.

TYLER: He’s as bad as she is. Here, what’s a time fissure?

DOCTOR: It’s a weakness in the fabric of space and time. Every haunted place has one, doesn’t it? That’s why they’re haunted. It’s a time distortion. This one must be very large. Large enough to have affected the place names round here. Like Fetchborough. Fetch. An apparition, hmm?

She is really there to provide the folk horror back story to contrast the alien/sci-fi aspects of the main narrative. Kneale utilises a number of similar narrative tricks using characters in his work – the policemen and old couple who remember the past cases of hauntings in the houses above the pit or the vicar who has records of exorcisms and the somewhat disturbed local man who used to visit the old house in his childhood with his mates to smash things up in ‘The Stone Tape‘. Without her character there wouldn’t be much to the coven/black magic strand of the story and as I said earlier, she works very well with Tom, for example in the scene where he wakes her from a coma by getting a fruit cake recipe wrong!

The final character is the rather grumpy Ted Moss – a council worker black magic occultist! he wouldn’t be out of place in ‘K9 and Company’, but he does get to deliver this cracker of a line:

LEELA: He came armed and silent.

DOCTOR: You must have been sent by Providence.

MOSS: No, I was sent by the Council to cut the verges.

Next up. The Fendahl is death, how do you kill death?

The Curious incident of the Dog in the Night Time

One thing I meant to mention when I talked about Adam Colby, was the curious case of Leakey, Colby’s Golden Labrador dog (‘you old bone hunter you’). Now some people have postulated that he was called Leaky, due to his territorial pissing. In reality it is Leakey with an e. Named after the Leakey family of archeologists, paleontologists and paleoanthropologists of the great rift valley of Kenya. Mainly Louis, Mary and Richard Leakey who between them discovered a number of very important early hominid skeletons and the site at Olduvai Gorge. It is intended to fit in thematically with the discovery of the skull of ‘Eustace’ in the same area in Kenya.

Richard Leakey was also head of the Kenyan Wildlife Service – which is the context I once very briefly met him in, at a lecture. His work in conservation and in particular his robust approach to anti-poaching patrols, won him few friends in Kenya and he subsequently lost both legs in a plane crash, suspected to be an act of sabotage.

I wonder what happened to Leakey, I don’t think we see him again after he discovers the body of the hiker. I do hope he was alright and some how escaped the direct continuum implosion to roam the fields and woodlands of Fetchborough, sniffing out bones!

The Fendahl is death. How do you kill death?

Hungry. It were hungry for my soul.

As a child, few ‘Doctor Who’ monsters captured my imagination quite so much as the Fendahl. Now that might sound surprising, but hear me out on this. This wasn’t especially from seeing the story on TV, although I did, but more through reading the Target novelisation afterwards. A creature that was death, something that you couldn’t kill. One that had evolved on a planet where evolution had gone down a blind alley and killed everything else, including members of its own species. One that had shaped and influenced the development of humans just to survive. It was really the first example, the final Quatermass story from 1979 being the other, of my attraction for ‘high concept’ ideas on TV, films and books. Something that would see me drawn to the works of Nigel Kneale, ‘The Prisoner’, 2001 and in the wider cultural context everything from Dennis Potter to Borges. The scares and the horror that pervade this story are delivered through the dialogue and the concepts, with only a few key visuals to support them – it is largely a psychological horror story for kids.

In this regard and perhaps rather mercifully, the Fendahleen creatures themselves are used quite sparingly in the TV serial. Their backstory though is drip fed through the story:

COLBY: Did you say that about twelve million years ago, on a nameless planet which no longer exists, evolution went up a blind alley?

DOCTOR: Yes.

COLBY: Natural selection turned back on itself and a creature evolved which prospered by absorbing the energy wavelengths of life itself?

DOCTOR: Mmm.

COLBY: It ate life? All life, including that of its own kind?

DOCTOR: Yes.

DOCTOR: The Fendahl is death. How do you kill death? No, what happened was this. The energy amassed by the Fendahl was stored in the skull and dissipated slowly as a biological transmutation field. Now, any appropriate lifeform that came within the field was altered so that it ultimately evolved into something suitable for the Fendahl to use.

COLBY: Are you saying that skull created man?

DOCTOR: No, I’m saying it may have effected his evolution.

DOCTOR: I think it’s the Fendahl. It grows and exists by death.

LEELA: Most creatures do. That is what you told me.

DOCTOR: The Fendahl absorbs the full spectrum of energy, what some people call a life force or soul. It eats life itself.

If the dialogue does most of the heavy lifting here, visually what sells the scares are the atmospheric point of view shots, as the creature moves in on the hiker and later the Doctor in the woods at night, the creature’s victims paralysed, rooted to the spot. That really is a nightmarish idea – a childhood bad dream. Or the shots of the creatures tail fluke and the trail of slime it leaves. When we actually the creature isn’t particularly brilliantly realised, but is very imaginative and if you search for images of Ragworm or especially King Ragworm, you will see the sort of look they were aiming for – some of them are absolutely terrifying. The creatures are killed by rock salt – one of Martha Tyler’s magical defences and the scientific explanation of how it affects the creatures mimics the use of the ancient magical defence of iron against the devil in ‘Quatermass’ and the Pit‘ – explained scientifically as it is used to earth the creature which has converted the mass of the ship into pure energy. Again this offers a scientific explanation for a folk superstition:

DOCTOR: Yes, sodium chloride. Obviously affects the conductivity, ruins the overall electrical balance and prevents control of localised disruption to the osmotic pressures.

LEELA: Salt kills it.

DOCTOR: I just said that. Probably the origin of throwing it over your shoulder.

The Fendahl itself is a gestalt – another favourite term of Nigel Kneale’s, used in ‘The Quatermass Experiment‘ and ‘Quatermass II’, used again in ‘Doctor Who’. in ‘Spearhead from Space‘ and the concept reused in ‘Ark in Space’. Conceptually, it is the group being greater than the sum of its parts – and comes from the German, used in an eponymous school of thinking by a number of early 20th century German psychologists and later a type of therapy. I always wondered whether his specific use of that term came from Kneale’s connection with Germany via his wife the children’s writer Judith Kerr, whose family had fled Nazi Germany.

Skull changed into a woman’s head and back again

The other aspect of the group creature being the core – in this case the transformed Thea Ransome. This is where most of the body horror of the piece comes into play, as Thea’s brain is restructured by her contact with the skull. Indeed, the glowing skull, merging with Thea, is one of the key, memorable images of the story. You could say it was burned into my own young brain in 1977.

There was a review of ‘Image of the Fendahl’ in an old DWM, where the writer quoted a piece of work by educationalist Cedric Cullingford on how children under 12 understand television, in which he argues in the case of ‘Doctor Who’ is in the form of ‘a series of clear images’ in amongst complex plot details. The children remembered what the images of what the Doctor, the TARDIS and K9 looked like and that the Doctor ‘fights monsters’. The thing that they remembered from the actual episode was basically the image of the skull glowing and something happening to Thea – the plot specifics and details were completely lost – ‘about a skeleton. Skull changed into a woman’s head and back again’ was the clearest of their recollections.

That this is also one of the final images of the episode is significant – the cliffhanger is the image that is left in the child’s mind. It was the image that was important, that lingered in memory the week after viewing it, the meaning only really important to older children and adults. And that is the way that I remember viewing the show as a child myself – it was the vivid images and cliffhangers that lingered, often the only way of working out what it all actually meant was reading the Target book a few years later when I was older and when I could re-read the difficult bits many rimes over and look up what they meant. From my childhood – well, yes I remember the glowing skull, in the same way that I remembered the Sea Devils rising from the sea or a giant spider hopping in Sarah’s back. It is an interesting way of looking at a ‘Doctor Who’ story – almost the opposite way that we look at that as adults – that the set-pieces and visual hooks are more important than a cohesive narrative or character or world building. Maybe we have got it completely wrong?

The story itself doesn’t linger long on the transformation of Thea or the coven coven members – it is horror rather than necessarily the body horror of her possession or transformation into the gold skinned goddess with staring eyes, that interest the author and the story doesn’t investigate this in the way that say ‘Ark in Space‘ or ‘Seeds of Doom‘ do. We don’t hear anything much from Thea herself about her condition or much from her colleagues or friends, it isn’t played as a primary aspect of the narrative as it would likely have been in say season 13 or 14.

Mythological horror

Another aspect that also sells the Fendahl as a menace is the Doctor’s reaction to them, they are built up as a horror from the Time Lord’s past. That sort of thing is ten a penny now (ancient Time Lord foes/weapons from the dark times etc.) – but at the time was quite novel and different. Even the Doctor himself seems scared, to the point of not thinking straight:

DOCTOR: I’ve got it. It is available in the Priory. The skull’s absorbing the energy released when the scanner beam damages the time fissure. Why didn’t I think of that before?

LEELA: Even you can’t think of everything.

DOCTOR: I can’t?

LEELA: No.

DOCTOR: No. Well, I should have thought it. I was frightened in childhood by a mythological horror.

LEELA: Oh.

DOCTOR: Too frightened to think clearly.

So there are two layers of folk horror mythology in this story. Firstly the stories of Grandma Tyler, the coven and the legends of the haunting of woods of Fetchborough and then those of the Doctor and his own people – the legend of the Fendahl, a creature whose potential was so great that the Time Lords placed a time loop around their planet to prevent them spreading to the rest of the universe. That is very clever, Terrance Dicks uses something similar in ‘State of Decay‘ – layering Time Lord mythology over middle-European folk tales of Vampires, with the e-space peasants a proxy for their earthly counterparts. We get both English and Time Lord Folk Horror for the price of one.

Whilst the ending of the story and the defeat of a menace that has been built up as incredibly dangerous, perhaps feels a bit perfunctory, the lengths they have to go to actually destroy the menace – trapping the core and the Fendahleen inside the imploding priory and having to drop the skull into the heart of a supernova, also help to sell the nature and scale of the menace. How do you kill death itself? Well, take all of that with a pinch of salt…

The Final image.

So we are left with a story that is often effective, though not without its issues and is to my mind a cut above anything else in season 15, bar the excellent ‘Horror of Fang Rock’. It is pretty well directed by George Spenton-Foster, especially the atmospheric scenes set in the woods at night in the mist or the pulsing glow of the skull attracting Thea or the Doctor, but without ever really getting near the best directed of classic stories. It isn’t the plunge into the abyss that some of the later stories in the season are in terms of production values, but sadly it is still a bit of a step down. In my head, there is a Hinchcliffe era version of the story which propels it into the top ranks of ‘Doctor Who’ stories, a better production, some of the rougher edges of the script smoothed and Tom’s ad-libbed contributions nipped in the bud a bit. As it is, it fuelled my childhood imagination and led partially at least to my love of the works of Nigel Kneale, which is no bad thing and as such, I will always have a place in my heart for it.

And, with regard to the TV series at least, this is the last we see of Chris Boucher. Which is a great shame. Robert Holmes made the mistake of recommending him instead of himself to the ‘Blake’s 7’ production team. And ‘Doctor Who’ lost its next script editor. Although maybe if he had taken the role, he would have ended up bludgeoning Tom Baker to death, so perhaps it is for the best! He returned to write a few novels of the BBC Books range – including ‘Corpse Marker‘, a sequel to ‘Robots of Death‘, but really I can’t help but feel that the show lost out on exploiting his talent more fully. His three scripts are never less than interesting and it would have been fascinating to see where his version of the show ended up, a very different place than season 15/16 I suspect. In that regard though, I wonder if in the climate of pressure from Mary Whitehouse and the star power that Tom Baker was starting to wield, whether his brand of smart SF, horror and a sarcastic, somewhat cynical world view would have worked.