The Dark Places of the Inside – an introduction to Kinda

‘You will agree to be me, this side of madness or the other’

In the October 1982 issue of Doctor Who Monthly (issue 69), ‘Kinda’, the left-field Buddhist parable of forest worlds, empire and the dark places of the inside, came bottom of the annual Season Survey with just 9%. It was ranked 3 places below ‘Time Fight’. If you are interested ‘Earthshock’ was top and ‘The Visitation’ second. If you were amongst those voters for voted for the story – pat yourself on the back! It is a little bit like being one of those who applauded Dylan going electric on his ’65/66 tour amongst the booing. Even back then I really couldn’t believe that ‘Kinda’ was so little loved – I really liked it and thought Simon Rouse as Hindle was the best guest performance of the season. Don’t get me wrong I had ‘Earthshock’ above it – I wasn’t that perverse a teenager and the Cybermen had just returned after a long absence, but it was certainly up there near the top of my list. Anyway, things change and ‘Kinda’ is now highly rated by many – in the last big DWM survey it came 63rd,. I found that surprisingly low, but perhaps this reflects the divisive nature of the story. These days most of the views I read on the story are largely positive, but at the time ‘Time Flight’ rated higher, let’s stop and have a think about that for a moment – that’s ‘Time Flight’.

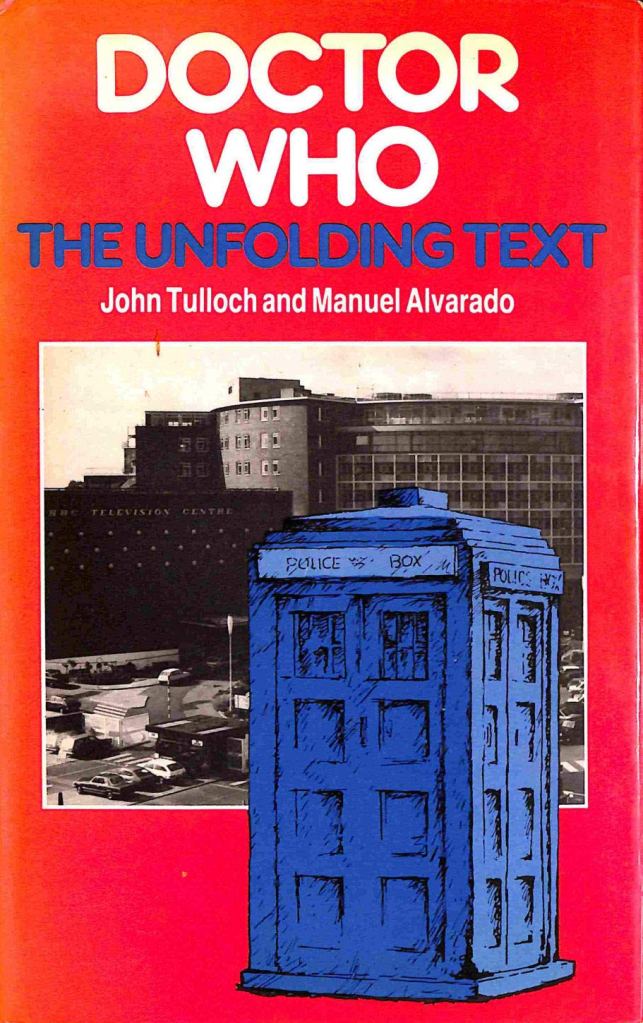

Anyway, the story features possession (Tegan and Aris), self and identity are questioned and challenged (Tegan again), Sanders and Hindle are ‘changed’, Panna ‘becomes’ Karuna, Aris finds voice during the story and the ‘souls’ of ‘the natives’ are captured in mirrors. It is therefore a perfect story for this thread. Before I look at the story, some thoughts on Chris Bailey. Kinda must be the most analysed Doctor Who story ever – some serious thought has gone into it, from the contemporary academic book ‘The Unfolding Text’, to a huge amount of fan effort and theory – involving everything from Ursula le Guin, to Tom Stoppard to Kate Bush. It is worth a few moments of anyone’s time listening to what Chris Bailey has to say on the subject – if nothing else he is an engaging, intelligent writer and well worth a listen. From the Kinda DVD there is an interview with the man by Rob Shearman – which is really lovely – quite touching actually, almost redemptive and for my money one of the best things on the DVD range. There are also the Kinda and Snakedance documentaries and the DWM interview with Bailey from issue 327, where Benjamin Cook managed to track him down and DWM 269 which interviews Simon Rouse and Nerys Hughes together. I will return to look at some of that after the review.

A few things of notes from those source materials though – Anicca and Anatta aren’t supposed (at least by the writer, but surely by the director Peter Grimwade?) to be Adric and Nyssa – although that makes sense in terms of the direction and choice of shots, the pith helmets weren’t his idea (JNT’s apparently – though Bailey did very much approve of casting Richard Todd as Sanders), the structure in the dark void (‘the Wherever’) wasn’t meant to be a representation of the TARDIS, but rather a gypsy caravan structure, he disapproved of the depiction of the Kinda (like a Timotei advert!) and apparently he hasn’t read the ‘Word for World is Forest’! He does however seem to really enjoy these theories and the fact that fans have their own takes on the meanings and themes of his work. Ultimately with a work like ‘Kinda’, the writer makes it open to our interpretation once it is out in the world. He credits the fans for their ability to see beyond the ‘tawdry’ production values and embrace the ideas contained in the story. As I say, I will look at his views on the story and the production process again after the main reviews.

Look, I am unlikely to come up with anything much new or earth shattering about Kinda, my brain doesn’t really do that – the best I can hope for is that I give you my views on the story as it unfolds and present them as elegantly as I can and analyse how they fit with the theme of this thread. I am likely to struggle with the Buddhist aspects of the text, but then so would a contemporary audience of largely non-Buddhists. Where I can I will try to add something of interest so in that spirit:

Firstly a short glossary of terms:

Mara – the Buddhist equivalent of a demon, relating to temptation, desire, greed, delusion and death

Dukkha – suffering, pain, sorrow or sadness (one of the three marks of existence with anatta and anicca)

Anatta – no self or soul, referring the Buddhist belief that there is no unchanging soul

Anicca – impermanence, that everything is change, transient and inconstant

Panna – wisdom, insight that reality consists of anicca, anatta, dukkha and sunyatta (emptiness)

Karuna – compassion, one of the four divine abodes (along with kindness, equanimity and joy).

Jhana – meditation

Deva – There are different classes of deva – supernatural beings (similar to deity – but not immortal gods) with god-like powers. It is worth noting that one of these is the mara.

Loka – World

So Deva Loka would be the world of the Mara?

I think my difficulty in putting that together and also understanding what those terms mean in anything but the most superficial way, in Buddhist philosophy – which derives from a culture that is far from my own, would also chime with the difficulty in understanding some of the concepts in ‘Kinda’ that a general UK or western audience would have. They are really interesting and thought-provoking, but I am never going to understand them properly and like other religions are open to interpretation even from within that world. I will maybe talk about some of these where relevant, but there are plenty of other things to discuss, as we venture into the dark places of the inside and too-green paradise of Deva Loka.

Paradise is too green

There are no predatory animals on Deva Loka. No diseases, no adverse environmental factors. The climate is constant within a five degree range and the trees fruit in sequence all the year round.

You know something? This is my fourteenth ex and rec, and I’ve never seen a planet like this one. Look at it. Paradise, isn’t it? The sun shines, the birds sing, food grows on trees. Even the ILF is friendly. Or used to be.

I think paradise is a little too green for me

Welcome to paradise, to Deva Loka – paradise. Either the Garden of Eden or the Buddhist world of deities. Or more likely a mixture of the two as Deva Loka spans both the Buddhist and Christian view of paradise or Eden. Likewise the Mara – temptation in Buddhist thinking or literally the serpent at work in the Garden of Eden, tempting Eve in the Christian view, so maybe not so far apart as I initially thought they might be. From Genesis (the biblical version – not ‘of the Daleks’ which I am more familiar with) the apple is represented a number of times across the story – in the dome The Doctor and Todd taste the ‘forbidden fruit’, later Tegan drops apples on Aris’s head after agreeing to become the Mara – a crossover of Christian myth and science (Newton), rather like the Kinda themselves – Buddhism and the double-helix.

The more familiar (at least to the target audience) religious iconography of Christianity is imported into the Buddhist philosophy at the heart of the story, I think to give the Western audience something to hold on to – something more certain, good versus evil against the more ambiguous, fluid Buddhist world view. In fact part of me wonders whether Kinda is really Chris Bailey’s attempt to reconcile Buddhism which he was studying at the time with the Christianity he grew up with. All of that is then shaped into something that could be made into a working Doctor Who story by three different script editors – Chris Bidmead, Anthony Root and Eric Saward – two of whom worked largely in sympatico with Bailey – any guesses as to the odd man out? I’m sure compromises were made and nuances lost along the way – but in a very British way out of the potential muddle and compromise comes something really rather special.

In the military terms of the inhabitants of the dome, Deva Loka is just plain old S14, a potential world for colonisation to ease a housing shortage at home. To Todd it is paradise. To Chris Bailey it is ‘a garden centre re-created in TV centre’! For all of its limitations and the production issues it caused, is rather beautiful. There are stories of having to order bags of leaves overnight to hide the studio floor and countless stoppages while it was re-redressed. I think Bailey maybe had in mind something darker – maybe it should really have been built at Ealing and shot on film. Whatever, I really rather like it. Something else that is beautiful is the incidental music by Peter Howell – especially the pastoral Kinda theme. The effect of both of these elements is to set Kinda up as somewhere that is paradise, beautiful and non-threatening, which regardless of what the writer had in mind when he visualised their world, actually matches what the script is trying to do. The soundscape of the wind chimes and the dreaming – which turn into the nightmare of ‘The Wherever’ or ‘the dark places of the inside’ is equally effective. Again, I’ll look at this later but the incidental music/soundscape of the Mara and their world is just nightmarish – it compliments the visuals perfectly and really adds to the production.

Culturally non-hostile

‘The Kinda pose no threat whatsoever to the security of this expedition. They are culturally non-hostile.‘

‘Of course, from their point of view, we might pose a threat to them.’

‘How do you mean? What point of view could they have? They’re savages.’

From the start the Kinda are setup as ‘non-hostile’. However, we have very different views of them from the intruders into their world – between the scientist Todd and military man Sanders. Culturally non-hostile versus savages, we might pose a threat to them versus standard procedure and hostage taking. In some ways the closest thing to the Kinda that we have elsewhere in Doctor Who are the ‘primitives’ in Colony in Space or even the Solonians in the Mutants – sophisticated societies (or formerly in the case of the primitives) that are just different to those of the colonists. However the Kinda are more ambiguous and so is the nature of the intrusion into to their world. ‘Colony in Space’ is more of a Western – settlers arriving and viewing the locals as primitive (similar to Sanders view here – but very different from Todd) or the more straightforward view of empire and it’s decline that we have in ‘the Mutants’.

Chris Bailey rather cruelly refers to the depiction of the Kinda as a ‘Timotei shampoo advert’, imagining instead a dirtier people – however I prefer to look at them as a version of Gauguin’s Polynesian paintings of women in Tahiti. Bailey’s is an interesting idea, maybe playing against type, but I don’t quite see how making them dirtier would fit with the idea of an advanced, but different civilisation. Without seeing what he had in mind, my initial response is that I don’t think it would entirely work – for most people, dirty and wearing rags is shorthand for primitive.

DOCTOR: Well, it could be the double helix.

TODD: It is. The heart of the chromosome. They all wear them.

DOCTOR: Thank you. What could they know of molecular biology?

Where Deva Loka is different or at least intended to be different, is that the so called ‘primitives’ or ‘savages’ are actually highly advanced, they communicate telepathically, wear necklaces depicting the double-helix – the molecular structure of DNA. They are supposed to be an advanced civilisation that has developed down a different path, not declined, just reached a stable point, equilibrium – their world gives them all that they need. In fact, the Kinda have stopped the wheel at a point where they seem happy in their paradise. The have food from the trees, a society, a social structure, wise women and anything potentially bad or uncertain is dispelled or undercut by ‘the Trickster’ poking fun of them. All of this is broken as Tegan provides a vector for the Mara to re-enter their world, the Trickster tries to do his job at the end of episode 3, but is killed in the process… and the wheel starts turning again.

For me, the idea of just being content and not continually growing and acquiring more is actually quite tempting. It fits in with several movements in ecological and sustainability thinking – concepts like ‘steady state’ or ‘zero growth’ economies and populations – where continual economic and population growth without heed of the consequences is deemed a bad thing – that the planet only has finite, often scarce resources and that there are ecosystem impacts from continual growth and acquisition. It fits with placing a value on ‘natural capital’ and ‘ecosystem services’ – environmental economics. The Kinda are in harmony with their world until the intervention of the Doctor and to a lesser degree (at least at this stage) the survey team.

Beyond the religious interpretation of paradise, the ‘paradise world’ is also a staple of science fiction and a representation of what happens to so-called primitive cultures when they meet imperialism. This is where the comparisons, whether valid or not with Ursula le Guin’s ‘Word for World is Forest’ come in. That story though is much more concerned with what happens when a culture based on capitalism and acquisition meets and exploits the world of Athshe through large-scale logging – exploitation of natural resources. All of that exists within ‘Kinda’ – but the team at the dome are only at the survey phase – we don’t really see them exploiting the Kinda – though that is supposed to follow. Here the worst they do is take two of them hostage – Sanders ‘standard procedure’. In the le Guin novel, there is a literal and allegorical rape. In Kinda the clash of different civilisations is present but not developed. It is more subtle, a cultural misunderstanding, a lack of common language or terms of reference. Instead through the intruders – The Doctor and Todd, we have a window into the world of the Kinda – both through their studies, talking to the wise women Panna and Karuna and also literally via the box of Jhana, which fosters a degree of cultural understanding and bridges the gap between imperialism and the indigenous peoples. The Doctor says:

‘We were seeing the world through their eyes’

This is pretty unique I think in Doctor Who – that the characters have a direct window into the world of one of the cultures involved. Sometimes this is developed through empathy between the Doctor or his companions with the other culture (Susan in ‘The Sensorites’ for example) – but here the Doctor and Todd see the world through their eyes – they aren’t changed by it like Sanders is, but they achieve greater understanding and empathy. In fact with exception of Adric (nothing changes him except for the Yucatan peninsula), only the Doctor and Todd – the most mentally agile, flexible and scientifically curious of the characters remain unchanged. In comparison and in reverse we also see the effects of the Kinda on the rigid, brittle minds of Hindle and Sanders – so this is a two way process. The intruders impact on the world of the Kinda and the world of the Kinda via the box of jhana and the Mara change and transform the intruders. In between these two different cultures sit the Mara – allowed back into the world via Tegan and the Doctor, who are from a third culture, but perhaps closer to those in the dome. Later the Mara is able to control the Kinda via Aris and his despair and resentment at his brother’s imprisonment at the dome. At the heart of all this though – if the Doctor and Tegan hadn’t visited Deva Loka the Mara would not necessarily have been released at all.

Performance codes and campness

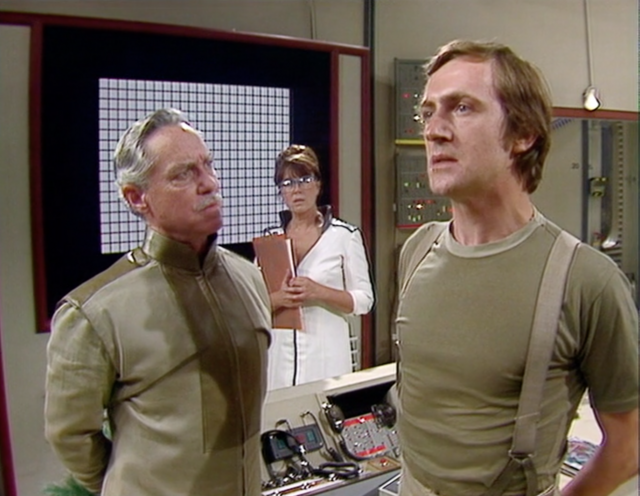

So, the other main protagonists in the story are the survey team from the dome – Sanders (Richard Todd), Hindle (Simon Rouse) and Todd (Nerys Hughes) all are extremely well cast. They are also very well written, they are established very early in the script – we know each of them from the opening scenes – it is an impressive piece of world building. All three performances are something that I’ve loved since my childhood, so they obviously made a huge impression on me.

Nerys Highes is fantastic as the more open minded scientist Todd. She is clearly very taken with Peter Davison’s Doctor – as a kindred spirit in a world where otherwise her conversation choices would be limited to Hindle or sanders. There appears to more to it than that though. I think I’ve always had a slight crush on her too – a saucy older female scientist, up for adventures in a far away rainforest – almost tailor made for me! As I’ve noted, Todd is the most flexible of these characters she already has some insight into the telepathy of the Kinda – and their sophistication, the double-helix. She is also less bound by the rules and regulations of Sanders and Hindle. So when she encounters a very different culture and the Mara, she is able to cope with this, deal with it and absorb into her bank of knowledge and experience, she has perspective. The others do not fare so well.

Sanders is another extremely well-drawn character. He could have just been a cipher, but his transformation by the box of jhana – regression to childhood, combined with they rather terrific performance by Richard Todd make him much more than just a gruff imperialist Sergeant Major. Richard Todd was a serious star in British film – there are few bigger roles in British war films than the hero Guy Gibson in ‘The Dambusters’, I can only think of Douglas Bader in ‘Reach for the Sky’. His other major films include the ‘Yangste Incident’ and ‘The Longest Day’. In 1963 he starred as Inspector Harry Sanders in ‘Drums across the River’ and its sequel ‘Coast of Skeletons’ (1965). This was a remake of the 1935 film ‘Sanders of the River’ (originally starring Leslie Banks) and based on the Edgar Walllace book of the same name. Sanders was a British Colonial Commissioner in West Africa. Wallace drew on his experiences as a reporter in Africa, for example he had witnessed the atrocities committed by colonial authorities in the Belgian Congo. So Richard Todd, along with the pith helmets is very much a shortcut for the older audience to say we are dealing with the British Empire here.

Simon Rouse as Hindle is one of the great performances in Doctor Who. He starts the piece as a slightly put upon junior member of the team, asleep on duty despite being designated SR security. During the story, his state of mind slowly collapses and he becomes a paranoid, childish bully who constructs his own world, almost like a child’s den to keep the real world outside. His mental state isn’t caused by the box of jhana or as far as I can see through contact with the Kinda – although he does control the two hostages via the mirror and they obviously are in telepathic contact with him. I assume it is the stress of the loss of Roberts and the 2 other crew members on an unfamiliar world, followed by his authority figure Sanders leaving the dome, leaving him rather unwisely in command. The shock of command seems to hasten his collapse and the return of Sanders in a child-like state, who instead of putting him back in his place then defers to his authority, reinforces his behaviour and makes it worse – like an errant child.

Before leaving Hindle in charge, Sanders says:

TODD: I really think you should think twice about leaving Hindle in command.

SANDERS: I never think twice about anything. Wastes too much time.

DOCTOR: He’s not altogether stable. In fact I think he’s on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

SANDERS: Well then, being in charge should do him some good, what? Might even make a man of him. Hindle!

Make a man of him? The exact opposite happens – it makes a child of him. More of that later.

‘Campness’ is something that comes up in a number of the source materials concerning the production of Kinda. The original end scene – Hindle and Sanders, walking off arm in arm, Hindle holding a flower was modified at the insistence of the producer. This was something that would have been overly camp in his view, descending into the sort of send-up he had disliked in the Williams/Adams era. All of which feels rather ironic with hindsight, but was very much his thinking at the time. It also comes up again in the interview with Simon Rouse and Nerys Hughes in DWM – Rouse says that sometimes he wished he had ‘camped up’ his performance more, and the rather lovely Nerys Hughes, basically tells him that no that would have been entirely the wrong approach – that you had to play Doctor Who with conviction – and she’s completely right – his performance is perfect as it is. It is extremely well judged – of the right ‘size’, but also played with a lightness of touch that guest cast in other stories really could have learnt from.

Blue Remembered Hills

‘Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.’

A.E. Houseman – ‘A Shropshire Lad’

‘You can’t mend people’

Hindle, Kinda 1982

In 1979 the BBC aired the Dennis Potter play ‘Blue Remembered Hills’. The title was inspired by the Houseman poem, which is in itself a paean to lost childhood. In the play adults (Colin Jeavons, Michael Elphick, Colin Welland and Helen Mirren) play children in the English countryside during the Second World War. The opening scene features Colin Welland’s character biting into an apple, which two of the children then have a fight over – representing the loss of childhood innocence. Childhood is a mixture of the innocent and the violent and the play doesn’t end well as one of the children is killed in a fire in a barn that the others have locked him in.

‘Outside is for grownups. It’s not for us, is it? Soon it’ll be finished, and then.And then, well, we’ll live forever and ever, won’t we.’

So adults playing children and the apple as a symbol of the loss of innocence were in the air when Kinda was being written and filmed in 1980/81. Sanders and Hindle regress to childhood – Sanders because he looks into the Box of Jhana, which changes him and Hindle undergoes ‘regression’ in the Freudian sense – the reversal of his ego to an earlier stage of development. It is almost as though his descent into madness is a variation on agoraphobia – fear of the outside, of open spaces or botanophobia – fear of plants and trees. The sort of trauma that city dwellers feel when they are transplanted to the countryside, to an unfamiliar world of greenery, unfamiliar noises and smells. Sanders becomes a beaming innocent, whilst Hindle becomes a spoiled childhood bully, one that wants everyone to play together, but also wants to be in control and sulks and threatens to take his toys away/blow up the dome when he isn’t.

ADRIC: No! I don’t want to play.

HINDLE: Why not?

ADRIC: Because I don’t want to. It’s childish.

HINDLE: Oh, go on. It isn’t a game, it’s real, with measuring and everything.

I love that line – ‘with measuring and everything’, it feels like it was written for me. It reminds me of how I’d like Doctor Who to be more overtly scientific or how I love a scientific paper or natural history text book with figures, tables, graphs and everything!

Hindle’s personality completely disintegrates in the course of the story, unfortunately rather than completely collapsing into him self; instead this manifests itself in him becoming a control freak – a child stretching to exert a deranged authority over the adult world. This is explicitly stated at the cliffhanger at the end of episode 2?

‘You forget, I’m now in command! I have the power of life and death over all of you!‘

His childish megalomania extends to building his own cardboard city (like Nero in that respect) that he can control inside the dome.

TODD: Tell me about the city.

HINDLE: Oh, do you like it? Never built a city before.

TODD: It’s very good. What’s that?

HINDLE: Oh, that’s my secret den. I’m the government as well, you know.

DOCTOR: And the security arrangements?

HINDLE: Security effectiveness one hundred percent. One thousand percent. One billion trillion trillion percent. Or more, perhaps.

These are some of the most memorable exchanges in the show’ history, they are quite unlike anything else I think. Played with utter conviction they become quite chilling – Hindle is out of control, a child playing with adult toys and lives, utterly unpredictable. And when things don’t go his way, like a child he wants to take away his toys and destroy the world:

HINDLE: Careful!

DOCTOR: I’m so sorry.

SANDERS: It’s easily mended. A drop of glue.

HINDLE: Don’t be silly! You can’t mend people, can you. You can’t mend people!

As it turns out you can mend people. In the story this is through Jhana (meditation) and also by looking into a mirror and seeing, recognising and confronting what you are. So maybe the self can be healed and repaired, but more of that later.

To avoid this coming even more cumbersome, I’ve split this into two and in the next part I will look at the core of the story – as Tegan enters ‘The Wherever’ – the world of the Mara where she has her self and identity challenged and agrees to her possession. I’ll also take a look at the role of the Doctor in the story, at the Kinda – Panna, Karuna and Aris, at the nature of the Mara and how the conclusion is handled as the Mara manifests itself as a growing pink snake – whatever are we supposed to make of that!

In the first part of the review I talked about the change and transformation of Hindle and Sanders and their regression to childhood. In the second part I will cover Tegan and her voyage into the world of the Mara, the temptation and possession of Aris, how Panna becomes Karuna and how a fool becomes an action hero.

‘You will agree to being me’

A significant thread is the mental attack and subsequent possession of Tegan by the Mara. This aspect of the story pivots around the scene in episode one as Tegan falls asleep beneath the wind chimes and falls into ‘the dreaming’, something that according to Karuna in episode 4 should only be done by a ‘shared mind’. This opens her up to the world of the Mara. This whole situation really is the Doctor’s fault – as annoying as Adric is, the Doctor is being a bit hypocritical accusing him of ‘meddling’, especially as he leaves the wind chimes he runs his hat along them in the same manner Adric has just been told off for. He then wanders off leaving Tegan to her own devices for 2 days in the forest.

Her transition into ‘The Wherever’ is beautifully realised. Peter Grimwade is about a good as director as 80’s Doctor Who has, at least until Graeme Harper turns up. He is one of the few to not only inject pace into the show, but also direct with flair and an eye for a set-piece visual. Here we have the camera track right into Tegan’s eye – through the pupil, pushing through into the darkness of the realm of the Mara. We haven’t had something as striking as this, I don’t think since Joyce/Harper and some of the imagery from ‘Warriors Gate’ – the gardens, the void and the spinning coin. If the forests of Deva Loka could possibly be slightly better realised, it has to be said the depiction of ‘the dark places of the inside’ is excellent. The crossover here with early 80’s music video – ‘Ashes to Ashes,’ ‘Fade to Grey’ etc. is palpable. Dukha, Annica and Anatta would be very much at home in any of these. Dukha in particular is a post-punk, new Romantic depiction of a sinister clown/trickster figure if ever I saw one. Even his accent, diction and the cynical, sneering bite he gives to his performance confirms this – you could recast this with John Lydon or even David Bowie and it would work perfectly.

‘You, my dear, cannot possibly exist, so go away’.

The scenes in ‘The Wherever’ are all about breaking down Tegan’s sense of self, challenging her identity to the point where she will break and do anything to make it stop – to agree to being possessed by the Mara. In the first scenes, which are overtly setup to reflect the opening scenes with Adric and Nyssa playing droughts, Anicca (impermanence) and Anatta (lack of self/non-self) challenge her very existence, ignoring her as an illusion in their world. This possibly reflects Tegan’s own view of how Adric and Nyssa (both scientific and mathematical prodigies) view her and treat her? Maybe she feels excluded slightly from the aspect of their world, looked down on, inadequate?

ANICCA: So you did see.

ANATTA: It proves nothing. Because an illusion is shared doesn’t mean it is real

ANICCA: Of course not.

ANATTA: Besides, how do I know that what you think you see

ANICCA: Is what you think you see?

ANATTA: Or vice versa

‘This side of madness or the other’

Dukha (suffering) treats Tegan rather differently:

TEGAN: I suppose you’re also going to tell me I don’t exist. Well?

DUKKHA: Don’t be silly. Of course you exist. How could you be here if you didn’t exist?

TEGAN: Am I dreaming you, is that it?

DUKKHA: Are you?

TEGAN: Or imagining you?

DUKKHA: Possibly.

TEGAN: Then I can abolish you, can’t I.

DUKKHA: Puzzling, isn’t it? And by the way, one thing. You will agree to being me sooner or later. This side of madness or the other.

He doesn’t question her existence. Instead he challenges her identity and sense of self. He is perhaps set up here to reflect her view of how the Doctor sees her? He first confronts Tegan with herself (something echoed in the resolution of the story) – not just a clone, rather another identical version of herself thinking the same thoughts, with the same personality and experiences.

DUKKHA: Have you changed your mind yet?

TEGAN: No. I have not.

DUKKHA: Oh good, because there’s someone I’d like you to meet. Or do you two already know each other? I hope you two are going to be friends. Do you think you will?

TEGAN: More tricks?

DUKKHA: Well, yes, I suppose so.

TEGAN: It’s a bit obvious, isn’t it?

DUKKHA: Oh yes, of course. A child could see through it. And that’s why I like it. Obviously one of you is real and the other an illusion created by me. That’s obvious, isn’t it.

TEGAN 2: Yes, it is.

DUKKHA: Is it? Well, in that case, all that remains is for you two ladies to work out which one of you is which. Obviously.

True to form the two Tegan’s seem to get on quite well together!

TEGAN: Come on, what are you thinking?

TEGAN 2: Don’t you know?

TEGAN: Maybe I do.

TEGAN 2: After all, apparently you’ll have been thinking it too, won’t you.

TEGAN: But I asked first.

TEGAN 2: So did I.

TEGAN: Look, stop it. If you must know, I was thinking about eating ice cream.

TEGAN 2: Yes.

TEGAN: What do you mean, yes?

TEGAN 2: So was I. I was three years old and I didn’t like the taste.

TEGAN: That’s my memory!

TEGAN 2: And mine! Stop it. Look, this is silly. What are we going to do?

Being presented with an exact copy of yourself that thinks they are you, has all the same experiences and can complete your sentences is a pretty scary concept. Someone else having the same face as you is bad enough, but someone with the exact same memories and thoughts is really disconcerting. All of these things make up your image of self, everything that is unique about you. It is similar to Deckard meeting Rachel in Blade Runner and telling her about own childhood memories, which she thinks are real, but have instead come from her creator’s niece. If these memories and thoughts aren’t unique – then what are you?

This then expands to being surrounded by many versions of her self and he challenges her to find the needle of her true self in a haystack of ‘Tegan’s (there’s a thought!). Directly after this immersion in a sea of herself, Dukkha subjects her to the opposite extreme as he isolates Tegan entirely alone in the darkness. This is sensory deprivation – which can either be used as therapy to relax and meditate or as a form of torture inducing extreme anxiety. Here it is the latter and is the final straw for Tegan and she agrees to allow the Mara to inhabit her body. That decision is something that allows the Mara back into Deva Loka and via Tegan into the minds of the Kinda.

Janet Fielding’s performance as the possessed Tegan is one of the best things she does in Doctor Who. By all accounts it is toned down form her original acting choice – which was much more overtly sensual and serpent-like. She is however much more overtly a sexual being in these scenes, laughing lasciviously, husky voice, shirt slightly undone, red mouth, teasing Aris in the scenes between them. She tempts him into accepting the Mara and like most men, he doesn’t need an awful lot of tempting! In the process he finds voice – but not his own, that of the Mara. All of this makes thematic sense – the Mara is temptation, so is the snake in Eden – Aris is tempted and the Mara enters the shared world of the Kinda again.

TEGAN: You are unhappy. Very unhappy. Perhaps I can help you free your brother from the dome. Would you like that? I thought you might. With my help, you could launch an attack, destroy the people who’ve held your brother prisoner. Yes, you’re right. The people in the dome are evil. With my help, Aris, you could become all powerful.

I am the Mara!

Do not resist. I am your strength!

The fool and the wise man

‘There is a difference between serious scientific investigation and meddling’

One thing that I’ve realised I rarely talk about in these reviews, except maybe when things go wrong on this count, is the Doctor and his role in the story. I had a think about why this was and I came to conclusion that he has always been there in my life – at least since I was 3. He has probably meant more to my development as a person than any religious figure, politician, author, playwright or even musician (which is saying a lot). He is the person who offers to shake the hand of another species, who calls aliens and monsters and villains ‘old chap’ – treats anything new as innocent until proven guilty, who offers a jelly baby, words of wisdom, silliness in the face of authority and righteous anger against tyranny. He is wise, protective, nurturing, silly, childlike, experienced, inventive and clever. The ultimate polymath and renaissance man. We know what his role in the story is – to represent civilisation, science, rational thinking and decency and to set things right. It normally doesn’t need spelling out what he is doing in a story. However this story is an exception I think.

The Doctor’s role in all of this is interesting. It feels slightly quite ambiguous – at least until the conclusion. To Panna, he is an idiot – he is male, yet unaffected by the box of jhana. Todd instinctively accepts him as an equal and confidant. Hindle perceives him as a threat – even though he is completely non-threatening. Until the end he doesn’t drive the story, he floats through it trying to gain understanding. There is a reason for that – which I will talk more about after the review, but it is basically because Kinda was originally written for the 4th Doctor and his role in this was going to be as wise old man, another archetype to those depicted, giving advice and guidance to resolve the situation. In contrast Saward was positioning the new, ‘younger’ Doctor to Bailey as more ‘a man of action’ – which he really isn’t.

Overall I think that the Fifth Doctor works better here than Tom would have. For the most part he is more like a pilgrim looking for enlightenment and having gained it through Jhana – seeing the world through the eyes of the Kinda, he then has the understanding of the Mara to drive through the conclusion. He is also in part idiot savant (I use that term in it’s wider definition – someone who is unworldly but gifted, rather than in reference to any degree of mental illness or learning difficulty), a mirror to the Trickster. Panna even calls him a fool – the equivalent to the Trickster in Shakespeare, whose plays are littered with ‘wise fools’. At the end he reverts to type – the action hero – arranging for the Mara to be trapped in the circle of mirrors. I don’t doubt Tom could have done all of that, especially in Season 18 mode, I do however have a hard time seeing how he would have fitted into the scenes with Hindle and the cardboard people – Peter Davison is perfect in those, the more dominant Tom Baker – I just can’t quite see it.

There is also a hint of something else. Something that we see very rarely at this point in ‘Doctor Who’ – something that might be more than just friendship developing between the Doctor and Todd .

TODD: Doctor. It’s only a guess, and guesses are not science. Have an apple.

DOCTOR: I thought the native produce was forbidden.

TODD: I’m a scientist. I do not feel bound by Hindle’s stupid precautions.

Again temptation! I really like this aspect of the story. I’m not sure if it is there is the script or just comes out of the chemistry between the two actors, but it works extremely well.

‘Such stuff as dreams are made of’

I’ve already talked about the Trickster and Aris, but the main representatives we have from the Kinda are the wise women, who have voice – the older Panna (wisdom) and younger Karuna (compassion). Panna represents wisdom and has the role of teacher – not just to Karuna, but also to Todd and the ‘blind male fool’ (the Doctor). She imparts the Buddhist ideas that underpin Deva Loka and the Kinda – the wheel turning and in the process bridges the cultural gap between the Kinda and intruders in her world.

PANNA: It is all beginning again.

DOCTOR: What is?

PANNA: What is? What is? History is, you male fool. History is. Time is. The great wheel will begin to roll down the hill gathering speed through the centuries, crushing everything in its path. Unstoppable until once again

TODD: Until?

PANNA: I must show you. That is why you have been brought here. Then perhaps when you understand, you will go away and leave us in peace. If it is not already too late.

DOCTOR: You said once again.

PANNA: Of course. Wheel turns, civilisations arise, wheel turns, civilisations fall.

DOCTOR: And I suppose this happens many times.

PANNA: Of course. Wherever the wheel turns, there is suffering, delusion and death. That much should be clear, even to an idiot. Now stop babbling and get ready.

DOCTOR: What do you know of the Mara?

PANNA: It is the Mara who now turn the wheel. It is the Mara who dance to the music of our despair. Our suffering is the Mara’s delight, our madness the Mara’s meat and drink. And now he has returned.

Mary Morris is superb here, in a story already packed with excellent performances, she lifts the story again to another level.

In a story already packed with images of change, transformation and possession, we also have:

TODD: It’s impossible.

DOCTOR: Well, unlikely, perhaps.

TODD: Ridiculous. I mean, if she is Panna, the wise woman, then where is Karuna? Answer me that.

KARUNA: Well, Doctor?

DOCTOR: Er, well, it’s a good scientific question. Where are you?

KARUNA: I am her.

DOCTOR: Both of you.

KARUNA: We are one.

DOCTOR: So, when Panna died, her knowledge and experience were passed over to you.

TODD: But how?

KARUNA: It is our way.

Out of wisdom arises compassion. I rather like that.

A serpent at the heart of TV centre

So the Mara straddles two religions. The name and part of the philosophy behind it obviously originates with Buddhism, but that religion doesn’t really have the concept of evil as Christians or societies like Britain that have a basis in Christianity but have become more secular might have. That presents a bit of an issue in 1970/80’s Doctor Who – what is the programme without a monster or villain? So the Mara is thenaugmented with Christian symbolism – the serpent in the Garden of Eden – temptation and sexual desire. Would the Mara have worked without the physical representation as a snake or literal representation of evil? Well it probably would – but I’m not sure about the level of ambiguity concerning what it wants and represents, maybe that would require an amount of sophistication amongst both the young and older casual audience with regard to the motivation of an adversary in ‘Doctor Who’ that doesn’t really exist and probably doesn’t even today? If the show were a niche science fiction series, it could behave differently and indeed it can afford to do so from time to time, but is primarily a family adventure show, designed to appeal to the widest possible audience. As such compromises are required.

So what are we to make of an ever-growing pink snake? This part of the story is a little bit of a let down, although you could argue with its themes of sexual temptation, the literal depiction of the snake as growing and pink works thematically at least – if not technically! JNT with his eye on reducing campness (!) and send-up in the show missed an enormous, expanding pink snake, really? It isn’t terrible, but it isn’t very good either and neither are the rubber snakes that Aris has to wrestle with on the ground. It might also be picky, but since the snake is huge, much larger than the mirrors, it isn’t technically trapped by it’s own reflection most of the time. What this ending to the story does give us is a switch in the mode of the Doctor from pilgrim and student to the galvanising force of nature that he normally is. Even in this case though he has to be prompted by Adric for the solution using the circle of mirrors. So, in the end Saward sort of gets his man of action he wants and it also gives JNT the monster that he thought Doctor Who needed. It might not be the ending that served the story best though. Something like the image of the snake skull shattering from Snakedance would probably have been more effective and cheaper than what we end up with. It all makes sense conceptually – the Mara is confronted with itself or is it more that Aris is confronted, like Tegan earlier, with his own self and what he has become and in the process he rejects the temptation of the Mara and what he has become?

Luckily then that the ending of the story works much better once that is all out of the way. We have Todd’s conversation with the Doctor about paradise, Tegan’s concern about whether she is rid of the Mara for good – clue she isn’t – I have Snakedance to come soon – so I guess that answers that question. Hindle and Sanders are healed – walking off into the forest smiling together and Deva Loka is safe, for now, from exploitation.

TODD: This planet is totally unsuitable for full-scale colonisation. That the unit be withdrawn. Sanders is pleased.

DOCTOR: Is he?

TODD: He wants to stay here. I told him he should just wander off into the forest. Nobody would notice. Shame about poor old Hindle, though.

DOCTOR: Oh, he’ll be all right. He was just driven out of his mind. Just what he needed. What about you, will you stay?

TODD: I don’t think so.

DOCTOR: You’re not tempted by paradise?

TODD: It was all right at first, but it’s all a bit too green for me.

Even Nyssa has woken up, unfortunately for her just in time to spend most of the next story in the TARDIS surrounded by bits of exploded android. It might be churlish given the strength of Janet Fielding’s performance in this, but oh, to kick the whole lot of them out and have the Doctor and Todd explore the universe together, him looking all bashful, her slightly doe-eyed and obviously besotted, but with the odd wicked, witty put-down. Her insight and empathy for alien cultures would have worked a treat and he would have worked well with a slightly older, mature, intelligent woman. Never mind, paradise was too green anyway.

So it has taken a while, but that is Kinda – change, transformation, possession, loss of self and identity. A story about a society that has stopped the wheel and the changes it brings, but where intruders through lack of cultural understanding re-start the process of change and where they are themselves changed by their experiences.

It is time to move on, well sort of – up next I am going to look at a contemporary book (Doctor Who – The Unfolding Text) and how it covered the production of Kinda.

The Unfolding Text – ‘Kinda – Conditions of Production and Performance’

When I was teenager in 1983, I bought a book, ‘Doctor Who the Unfolding Text’ by John Tulloch and Manuel Alvarado. Although I didn’t understand what semiotic thickness meant or any of it really, I was a precocious, slightly pretentious know-all teenager, who had just watched ‘The Prisoner’ for the first time and so trying to decipher what all of this meant this was right up my street. Contained within the tome, amongst the media studies speak (in retrospect a load of old toss that sounded vaguely scientific – a bit like Who in that respect) – were a series of references to Jungian philosophy and Ursula le Guin’s ‘The Word for World is Forest’ in relation to ‘Kinda’ and an entire chapter devoted to the production and scripting of the story.

Outside of the media studies analysis and comment (which I am really not qualified to talk about), this chapter ‘Kinda – Conditions of Production and Performance’ contains contemporary comment from most of the main production staff and makes for fascinating reading. Of particular interest are the quotes from the author, Chris Bailey on Buddhism, Christianity, empire and the influences on the script for ‘Kinda’ and tensions during the production process. The chapter really concerns how an authorial voice – Bailey here, then has his work pass through a process whereby it is subject to the views, experiences, preferences and professional abilities of the production staff – from script editor, director, producer, designer, special effects designers, incidental music composer and actors – all of whom depending on your point of view might at best enhance the finished production or at worst clash with or undermine the authors ideas. We have a little of both here. It is a two way process though and some of the production staff have a valid point with regard to framing a story within the ongoing format of Doctor Who as a series.

This last point is something that I think that fans sometimes forget. If you really like something or really dislike something it might not even have been written by the script writer, it might not even have been written or re-written by the script editor, it might have been at the insistence of the producer, the director or a last minute change by the cast. Even the storyline or subject will have been pre-selected by script editor and producer – it might already have been changed and shaped by them before the writer even starts the script. The production process might not be as collaborative as say theatre (something Bailey clearly isn’t happy about), but what comes out of the other end of the process is the work of many hands and often the success or failure of a story doesn’t necessarily rest with the people we attribute it to.

The interviews with Chris Bailey in DWM and on the DVD documentaries are many years after the fact. In the interviews for this book the wounds are still raw and the memories not yet clouded by time. Bailey is in the process of writing ‘Snakedance’, so although his ideas maybe clashed with the requirements of Saward and JNT and he was appalled by the ‘tawdry’ production values of ‘Kinda’, both sides obviously didn’t hold enough a grudge to avoid working together again. Rather than reviewing the whole lengthy chapter, I am just going to pick out some of the key quotes.

Here Bailey is talking about Saward’s requirement to explain some of the plot points:

Bailey: ‘The analogy I used at one fairly ‘hairy’ stage in the writing, when I was being asked to explain something totally, was that… if it was a Doctor who version of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ .. they’d say, ‘Now how is this wolf going to be able to impersonate a Grandmother’? And then somebody would say ‘Well of course, it’s the mind-transfer fibrulator on the wall’. These things get explained too much – or not really explained. There’s a sense in which you throw together a few words about the ‘ambivalent time and space condenser’, and a sort of pseudo explanation of what is going on’

That is the sensibility of the author clashing with a central tenet of the show – that the universe is scientifically explicable, even if the science isn’t necessarily understandable by the viewers. Magic doesn’t exist, but the advanced science of the Daemons or Osirians or Time Lords can appear like magic to the 20th or 21st century audience. Also, maybe Bailey overestimates the audience slightly as I imagine even in its transmitted form ‘Kinda’ probably completely confused most of the 8-9 million people watching. It might have sparked the imagination of some of the posters on here, but as I noted into the introduction, even the readership of DWM was unimpressed at the time – preferring the more traditional ‘Earthshock’ or ‘The Visitation’.

Bailey: ‘What we have now is a snake which moves from arm to arm, which is very, very obvious… Its hammering the point into the ground in terms of technology. The idea that you can do it through an actor is not on… Simon Rouse plays Hindle as a madman…purely out of him as an actor. There were no snakes and disappearing boxes. The production team got his acting power there, but they seemed quite surprised.’

Saward replies to this:

Saward: ‘It’s true that we wanted snakes and things to be hard and positive and originally Chris Bailey didn’t… We are attempting to appeal to a very broad audience of all ages, of all backgrounds.. All the Buddhist stuff in Chris’s script, all the symbolism and so on – it’s there if you can get it…if you know about it. But when children are sitting there, they want something that will help them along too’

That strikes me as actually a perfectly reasonable thing to say. We are talking about a mid-week, early evening family audience of around 8-9 million viewers, not an avant-garde theatre audience.

There are also clashes between Bailey’s vision and the requirements of director Peter Grimwade, particularly with regard to the pace of the show:

Grimwade: ‘I’ve got to make a show that is pacy. If it doesn’t work the way it is suggested on the page then it’s got to go’

Grimwade: ‘I would say that we all disagree with the writer in that respect, because the writer wants to do ‘Play of the Month’ and he happens to be writing it in the ‘Doctor Who’ slot. He’d be happy if we could cut the Doctor out. I think he is a very untypical writer in that respect and he’s using the programme as a peg for a particular style of writing… But I’ve got to make a show that is pacy’

The chapter then discusses the tensions between ‘serious drama’ versus ‘popular entertainment’. Amongst all of this, there is a great quote from Terrance Dicks about the show, which I haven’t heard before:

‘Doctor Who is a very intellectual show…concealed under the guise of an action-adventure programme for the family’

I really like this and it sums the show up perfectly for me. When I really dislike the show or aspects of it, it is because it is no longer clever, when it is dumb, I really feel like it has personally let me down. I am proud of it when it smuggles its cleverness in amongst the adventure, horror and comedy. I’ll return to this in a later review.

On the way that the possession of Tegan and the nature of the Mara is portrayed, Bailey has this to say:

Bailey: ‘Originally Tegan was taken over by a force from within which, in fact, is just one aspect of herself – called the Mara – but which has ended up pretty near to being a full-blooded demon.. In Buddhism there is no evil. There is no devil. So it is very difficult to write for Doctor Who… In my original version the Mara was quite an ambivalent thing. In Tegan, she became quite mischievous and sexy – quite flirty and lascivious. And Aris…became filled with desire for revenge. The Mara took a different form depending on the form it was occupying. And the snake didn’t exist. But in the process of brightening it up, colouring it up …’

That is a nice idea, the more I think about it the more I like it – I did touch on this aspect in my review, so it is obviously still in the final production – the temptation of Aris for revenge, the lasciviousness of Tegan, but really that is just a bit too subtle for a family adventure show. It needs something more tangible and the snake imagery provides that. That isn’t something to be derided it is the nature of the show and its audience.

There are also interesting quotes on the use of Buddhism in the story:

Bailey: ’One way Buddhism percolates through is that I tried to set myself to write it without people being killed all along the way. Very often this type of programme gets its tension over a pike of dead bodies… The original idea was the wheel of life – a Tibetan concept – the wheel which continues to revolve and on which we are all broken. The aim of Buddhist practice is to stop this wheel and the paradise that the Kinda inhabit is a paradise in which that wheel has stopped and the threat is that the wheel will start again’

I wonder what might clash with Eric’s ideas there? ‘A pile of dead bodies you say, now there’s an idea!’

It is clear from the interviews with Grimwade that he is very clever and whilst he disagrees with some of the author’s methods and intentions within the framework of ‘Doctor Who’, he does understand the piece and is able to bring that understanding to the actors:

‘In rehearsal the actors very much wanted Karuna to pretend to be Panna and put on Mary Morris’s voice. But I said no, I don’t think it works like that because in fact the idea is that there are two of them, there are two elements of wisdom and love/compassion which are complimentary. But at the same time they are the same thing and because Panna is dead and because Karuna represents love and compassion she is Panna because through love and compassion you therefore have wisdom’

One of the other things I talked about in the review was the role of the Doctor and how this changed with the transition of the story from something written for Tom to the final story for Peter Davison. I’m not sure I agree with Bailey here. Davison’s Doctor really isn’t an action hero, no matter what Saward says. He is quite the opposite I would say – bookish, boyishly enthusiastic, optimistic, clever, but struggles to convince others of his authority in the way that most other Doctor’s can. He isn’t lacking in wisdom, just the authority to impart it to others. This neatly reflects Davison’s own view that he was too young and not quite right for the role – in some ways he incorporates that into his performance. He isn’t bottom of the Jungian hierarchy, he is still at the top, but trapped in this new young body and less authoritative personality, the wise old man struggles to be heard. The book also has some very interesting discussion on Jung and the role of the Doctor and the Trickster in ‘Kinda’, most of which I missed in my review, as it isn’t really an area of expertise for me.

Also fascinating is the visual effects designer, Peter Logan feeling cheated and complaining about both the lack of opportunities ‘Kinda’ offered along with the lack of time allocated to them. Well apart from the massive pink snake to build obviously. He complains that the story doesn’t match up to the opportunities offered by ‘Destiny of the Daleks’.

The chapter is also very good on this era’s reaction against the perceived campness and send-up of the Williams/Adams era. That might seem an odd notion if you grew up with season 23/24, but it was very much JNT’s thinking at the time and is more how I remember his time as producer – seasons 18-21, than the mess that was to follow. This also chimed very much with the thinking of executive producer Barry Letts and script editor Chris Bidmead – moving the show back to what they perceived to be it’s strengths. I’d love to know what Barry Letts made of the Buddhism in ‘Kinda’, but unfortunately we don’t find that out. JNT did work on the show under the previous regime, but comes across here as someone who is very much reacting against all of the things that he did not like about those experiences. Much as the Williams era was a reaction against the things in the Hinchcliffe/Holmes era that had caused such consternation in Mary Whitehouse and her cronies, JNT/Bidmead was a reaction against the perceived excesses of the Williams/Adams era.

Overall, the chapter is a fascinating read, I haven’t really covered the authors analysis of the production process or their section on the comparison between ‘Word for World is Forest’ and ‘Kinda’, but really the fascinating part of the chapter really was the contemporary commentary on it and the tensions during the production with the key players in the production and writing process. I naturally want to side with Bailey, but also have to admit there is some sense from the likes of Saward and Grimwade – they aren’t making a one-off adult drama or a play. Doctor Who affords the author a platform for his ideas and a fantasy world for these to play out in, but in return ‘Doctor Who’ is it’s own thing and any writer within that format should pay it it’s dues and respect the expectations of its audience. I’ll return to this theme in the review of ‘Snakedance’. My final thought on this chapter and on ‘Kinda’ as a whole is that it works precisely because it is a blend of both approaches – the new ideas of Bailey made more palatable for the audience as it moved through the production process.