There are two events in everybody’s life that nobody remembers. Two moments experienced by every living thing, yet no one remembers anything about them. Nobody remembers being born and nobody remembers dying.

As you come into this world, something else is also born. You begin your life, and it begins a journey towards you. It moves slowly, but it never stops. Wherever you go, whatever path you take, it will follow. Never faster, never slower, always coming. You will run. It will walk. You will rest. It will not. One day, you will linger in the same place too long. You will sit too still or sleep too deep, and when, too late, you rise to go, you will notice a second shadow next to yours. Your life will then be over.

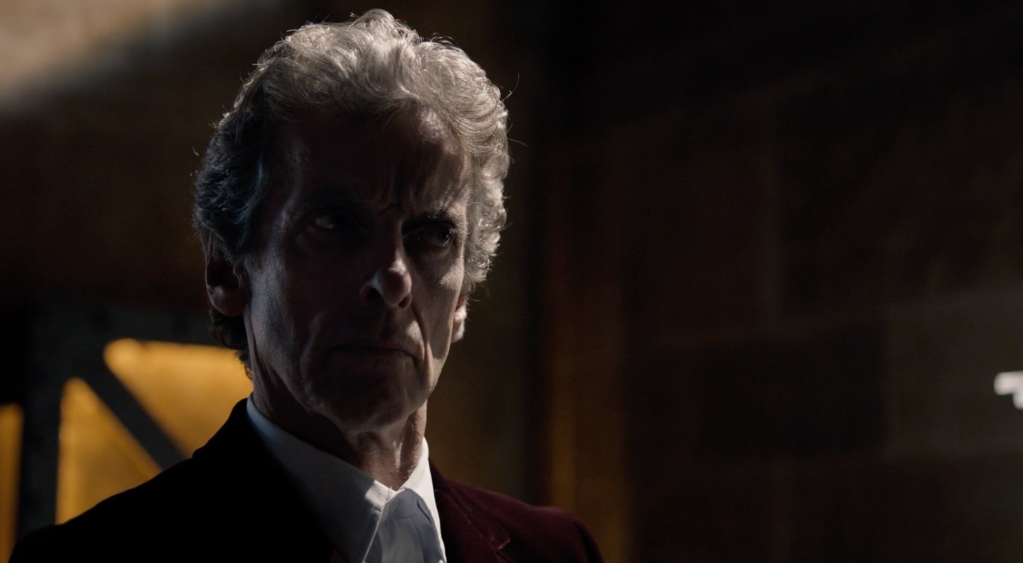

‘Heaven Sent’ might just be the greatest ‘Doctor Who’ story ever made, it is certainly the most profound and affecting and I am going to try to justify that statement across this review. It is an extraordinary piece of TV drama – beautifully acted, featuring an electric solo performance by the lead, exquisitely written – rich in theme and image, beautifully directed, designed and lit and featuring a score that has never been bettered in the shows history. And yet, I still can’t quite consider it my personal favourite story. Don’t get me wrong, it’s up there with the very, very best, but it is just too difficult a watch, too bleak, too melancholy (even for my tastes), despite also having moments of light and hope, for me to think about it quite in that way. I’ll try to reconcile those two perspectives as we go along.

The Day you lose someone…

More than any other ‘Doctor Who’ story, ‘Heaven Sent’ is about death, loss and grief. It is a reaction to the Doctor’s own very recent loss and examines how he deals with bereavement – by fighting back against the world and in the end, in the following story ‘Hell Bent’ ultimately going far too far. At the same time, it is also a ‘Doctor Who’ story and there are monsters to be fought – personal and real. Grief might be the Doctor’s principal enemy here in this story, but there are still actual monsters to be found and fought – those responsible for Clara’s death and for imprisoning the Doctor in his own torture chamber. To face them he has to survive this ordeal and in doing this he relies on the same methods that most of us use to survive loss, the memories of his loved one help him though it and urge him on to survive and ‘win’.

This isn’t even subtext – it is all there front and centre in this most unusual of stories. Steven Moffat was interviewed on the subject in DWM and spoke about wanting to depict grief and loss in a story and some of the difficulties of doing that within the show’s format and why he felt he had failed to do this adequately in previous attempts:

“‘The problem is, ‘Doctor Who’ is always about the new adventure, not the aftermath of the last one. Structurally, that’s incredibly important to how the show works. So you have to make grief he centre of the story, not a hangover from last week getting in the way of a new adventure. Grief has to be be the new adventure I thought ‘If he Doctor loses Clara in the most horrific circumstance, a circumstance where events pass out of his control, but which is partly his own fault because he’s made somebody think that they can act like him, and they can’t.. Essentially I was thinking “What is grief How do I make grief the monster of the week in ‘Doctor Who'”

“People always talk about grief as being alone, so I made the Doctor absolutely alone. Grief comes and finds you every time you stop or rest, so I gave him the Veil. And grief is waking up to the same pain every day, and trying to smash through it, so I gave him a diamond wall to punch for the rest of time. Basically he wore away the mountain with his tears. I was aiming for poetry. Tried for poetry, ended up with a gimmick. I’ve defined myself!“

It wouldn’t be Steven Moffat if there wasn’t also a gag attached to it, he goes on to compare the Doctor’s ordeal to the lot of the showrunner – “I do think that there is a reading of it that living the same life over and over again while you smash your face against a wall of pure diamond is roughly what it is like making ‘Doctor Who’. You kill yourself every time and then you get up and do it again. You never stop!”

That is Steven though, adding gallows humour to a profound and serious piece of work that just happens to be framed within a children’s action adventure sci-fi show. It really is a beautiful, truthful piece of writing – one he should be truly proud of. For me, the key line about grief and loss in the story is both brilliant and cruelly truthful:

‘The day you lose someone isn’t the worst. At least you’ve got something to do. It’s all the days they stay dead.’

Anyone who has suffered personal loss will understand that. That ache. That hole in your life. Something that can only be made better by adding time and the memories of happier times spent together. That day though, there is so much to do, so much to organise, it is as much about practical details of dying as it is about loss. A funeral is the traditional, ritual marker of the end of that period – from then on it is just loss and how you deal with it. Sadly, I don’t think that Steven Moffat or anyone else writing for the show for that matter, ever wrote anything more truthful.

Facing the consequences of ‘Face the Raven’

To recap, in the previous story, ‘Face the Raven’, the Doctor’s best friend Clara dies, killed by the Quantum Shade in what was really just a trap for the Doctor – a literal ‘Trap Street’. And brutally, Clara dies because of the Doctor, she has become too close to his world, because she tried too hard to be like him, to act in the way that he would, using everything she had learned of his methods. All to no avail. So, he feels not only the loss of a close friend, but also responsibility for creating this situation – something that he hinted at in ‘Face the Raven’ and even earlier, really at least since ‘Flatline’ – she had been enjoying the danger far too much and becoming reckless with it. It is an echo of Rory’s words to the Doctor in ‘Vampires of Venice’: ‘You know what’s dangerous about you? It’s not that you make people take risks, it’s that you make them want to impress you. You make it so they don’t want to let you down’. It is etched in his sad, old face in ‘Heaven Sent’ – ‘That sad old smile’ – his loss and his sense of guilt.

It isn’t only his grief at the loss of Clara though. This story is more about death than almost any other – more than even ‘Death in Heaven’ with its journey into the afterlife, the underworld of Orpheus – as not only is the Doctor stalked through his own personal prison by his own personal representation of death – ‘The Veil’, he also dies, only to be reborn, billions of times in a loop. The ever-growing pile of skulls in the sea surrounding the castle as evidence of this. Every time digging his own grave. Holding his own skull in his hand on the castle walls overlooking the sea – his very own Elsinore, the Doctor as Hamlet. Or running the sands of time through his hands – his own mortality trickling away. Or exiting via a tunnel leading to a bright light. Does any other ‘Doctor Who’ story have as many deaths? Maybe ‘Logopolis’ as the entropy field wipes out countless worlds? Well, in this case it is the same death, looped billions of times, resurrected by the transmat (sort of ‘Revenge of the Cybermen’ via the ghosting of ‘Silence in the Library’) but even so. And yet despite all of this ‘Heaven Sent’ manages to be deeply personal, intimate and almost small in scale. And through the story the Doctor finds the strength to go on, to fight and to win, all via his memories of Clara – the person he has lost.

So, we have images of death running right through the core of this, billions of deaths, a personification of death and the grief of a hero for his friend. It is fair to say that this isn’t ‘Doctor Who’ as light comedy. It also isn’t an easy watch. It is however extremely compelling drama and despite the darkness and subject matter it is a story I keep returning to time and time again, finding new aspects and nuance to it with every watch.

The Castle – my own bespoke torture chamber

Sorry I’m late. Jumped out of a window. Certain death. Don’t you want to know how I survived? Go on. Ask me! No, of course I had to jump! The first rule of being interrogated is that you are the only irreplaceable person in the torture chamber. The room is yours, so work it. If they’re going to threaten you with death, show them who’s boss. Die faster. And you’ve seen me do that more often than most. Isn’t that right, Clara? Rule one of dying, don’t. Rule two, slow down.

The Doctor is trapped in a bespoke prison. A clockwork castle, the rooms rotating and changing position, much like the TARDIS in that respect – it is after all Time Lord technology. I recently heard a podcast where Steven Moffat discussed ‘Once upon a Time‘ – the penultimate episode of ‘The Prisoner‘ and this piece has something in common with that series – albeit pushed in a different direction tonally. The very British whimsy of the Village, replaced by a much darker, more baroque setting. It shares the confinement, the righteous anger and relentless pacing of the hero (Peter Capaldi would make an amazing No. 6, should someone decide to remake the series again) and sense of escape and retribution against your captors. It also shares the high concept, philosophical feel of the 1960’s drama and ultimately it probably confused the wider audience just as much..

The location of a castle set in the sea though, taps into a much more timeless source than the Village, it harks back to fairytale and classic stories of the noble hero imprisoned without hope. And also to Hamlet and Elsinore and soliloquies on life and death and the nature of mortality. It is an incredibly astute setting for all of those reasons. And then because this is ‘Doctor Who’ and because it is Time Lord technology it has yet more layers – we have time and the looping of the Doctor’s life in prison and his death and we have a castle in the sea that can fit in the palm of your hand. In a confession dial in fact. A device cunningly set up earlier in the season and one that explains the raison d’etre of the piece. It is a device to force the Doctor to tell the truth, to confess. Part religious – confession is good for the soul, part torture device – confess or face your own worst fear, your own bespoke personification of death. And let’s be honest, it just looks beautiful – all courtesy of the brilliant direction of Rachel Talalay, lighting of Director of Photography Stuart Biddlecombe and perhaps one of the great unsung heroes of ‘Doctor Who’ – the quite brilliant design work of the late Michael Pickwoad.

Parting, piercing or lifting the veil

I always think of ‘Heaven Sent‘ as a solo performance (and what a performance) from Peter Capaldi, possibly the single best performance by anyone playing the role. We also have a brief appearance from as Clara and of course we have his nemesis – the Veil. An image from his childhood nightmares – the frankly grotesque ‘when I was a very little boy, there was an old lady who died. They covered her in veils, but it was a hot, sunny day, and the flies came. It gave me nightmares for years’. The Veil slowly and deliberately pursues the Doctor around the castle and can only be stopped by a confession. It also ends his life each time in the loop, triggering another cycle. The Veil – well the phrase ‘piercing’ or ‘lifting’ or ‘parting the veil’ has a number of meanings (even a corporate legal definition), but generally it can be characterised as meaning opening a door to the ‘other’ – to some truth, to something supernatural or the next life or whatever lies beyond death. In that regards its name reveals its function within the narrative.

The Prisoner

It would be remiss of me not to single out Peter Capaldi in all of this. He is simply astonishing in ‘Heaven Sent‘. Switching effortlessly between a brutal depiction of loss, to a wistful sad old smile, to righteous anger, to maniacally solving the intellectual puzzle of this world, all whilst about to be killed by the Veil or when leaping from the castle window into the sea below or punching a diamond wall or crawling, slowly and painfully back to the transmat to start the process all over again. He is incredible – I”m struggling to think of another actor in the role that could match this – only John Hurt or Christopher Eccleston would come close I think. But really this is all about Peter Capaldi – it is precision built to showcase his talent, to play to his specific strengths and he really grasps the opportunity and delivers an acting masterclass.

The Shepherd Boy, the sea, the stars, the mountain and the bird

At the centre of the story is a fairy tale. One written by the Brothers Grimm, published in 1815 – ‘The Shepherd Boy‘. Elements from the story are scattered across “Heaven Sent‘ and one is so important to the resolution of the narrative, that without knowing the source story (nobody watching in our house did), “Heaven Sent‘ is much, much less effective, if not downright confusing!

There was once on a time a shepherd boy whose fame spread far and wide because of the wise answers which he gave to every question. The King of the country heard of it likewise, but did not believe it, and sent for the boy. Then he said to him, “If thou canst give me an answer to three questions which I will ask thee, I will look on thee as my own child, and thou shalt dwell with me in my royal palace.” The boy said, “What are the three questions?”

The Sea

`The King said, “The first is, how many drops of water are there in the ocean?” The shepherd boy answered, “Lord King, if you will have all the rivers on earth dammed up so that not a single drop runs from them into the sea until I have counted it, I will tell you how many drops there are in the sea.”

In ‘Heaven Sent‘ The castle is surrounded by the sea, it is an essential part of the Doctor’ initial escape from the veil and his dawning realisation of the rules of the world he finds himself in. Of the significance of the pile of skulls he finds as he dives down into the depths. It is less the counting of drops of water in the sea, but rather the skulls that helps the Doctor understand his predicament and measure time passing.

‘One hope. Salt. Thought I smelled it earlier. When I broke the window, I was sure. Salty air. This castle is standing in the sea. Diving into water from a great height is no guarantee of survival. I need to know exactly how far I’m going to fall, and how fast. Why do you think I threw the stool? Fall time to impact seven seconds. Because you won’t see this coming!

The Stars

The King said, “The next question is, how many stars are there in the sky?” The shepherd boy said, “Give me a great sheet of white paper,” and then he made so many fine points on it with a pen that they could scarcely be seen, and it was all but impossible to count them; anyone who looked at them would have lost his sight. Then he said, “There are as many stars in the sky as there are points on the paper; just count them.” But no one was able to do it.

And the Doctor looks at the stars and realises that they are all wrong – wrong for the time period and he realises that seven thousand, a million or a billion years have passed. That he hasn’t travelled in time, but rather taken the long way home, looping in billions of iterations of life and death until this point.

And the stars, they weren’t in the wrong place, and I haven’t time travelled. I’ve just been here a very, very long time. Every room resets. Remember I told you that? Every room reverts to its original condition. Logically, the teleporter should do the same. Teleporter. Fancy word. Just like 3D printers, really, except they break down living matter and information, and transmit it. All you have to do is add energy. The room has reset, returned to its original condition when I arrived. That means there’s a copy of me still in the hard drive. Me, exactly as I was, when I first got here, seven thousand years ago. All I have to find is some energy.

The Mountain and the bird

“The third question is, how many seconds of time are there in eternity.” Then said the shepherd boy, “In Lower Pomerania is the Diamond Mountain, which is two miles and a half high, two miles and a half wide, and two miles and a half in depth; every hundred years a little bird comes and sharpens its beak on it, and when the whole mountain is worn away by this, then the first second of eternity will be over.”

And the Doctor realises the significance at the end of the cycle of the word ‘BIRD” etched in the sands of time in the teleport chamber. The meaning of the tale of the Shepherd Boy, the bird sharpening its beak on a diamond mountain every hundred years, wearing it slowly down and its relation to eternity, its sense of scale as a marker of the passing of time. The wall in this case is azbantium, marked ‘Home’ and the exit from this prison. The route to the Doctor’s reckoning with the people who have trapped him here and taken away his best friend. The Doctor is the bird and through a million or more years he punches his way through the wall and towards the bright light at the end of the diamond tunnel. To Gallifrey and a reckoning with Rassilon.

All of this is made explicit in the beautiful montage sequence where the Doctor loops endlessly through the cycle, punching the wall, mortally injured, left for dead at the hands of the Veil, dragging himself in agony back to the transmat, giving his last energy to operate it once more to repeat the cycle, is simply an astonishing piece of work from all concerned. Murray Gold’s music ‘The Shepherd Boy‘ is his finest work I think. Credit must also go to the editor of this section, it is so artfully done, cycling through events, but in a beautifully curated way, each cycle slightly different, pacing perfectly choreographed matched to ‘The Shepherd Boy‘ theme, a dance to the of music time.

Home – the long way round

Go to the city. Find somebody important. Tell them I’m back. Tell them, I know what they did, and I’m on my way. And if they ask you who I am, tell them I came the long way round.

Until finally, having carved a tunnel through the diamond wall, following the heavenly light, the Doctor breaks free. The Veil as a marker of time, falls like a previous Steven Moffat motif into a pile of clockwork cogs. And the Doctor, full of righteous anger is on his way to his own home, having taken the long way around, not quite the return he planned in ‘Day of the Doctor‘ or a heroes return for the ‘man who won the Time War‘. There is reckoning to be had and it might not have been Clara’s wish, but the Doctor will have his revenge.

‘You must think that’s a hell of a long time, Personally, I think that’s a hell of a bird.’

A common issue with ‘Doctor Who’ stories, particularly those in the 45 minute format is the rushed ending or the unsatisfying magic potion plot resolution or the dreaded ‘Deus ex Machina’. Nobody could accuse “Heaven Sent‘ of that. It is nearly all resolution, an escape billions of years in the making, not exactly ‘with one bound he was free‘. At the most you could accuse it of being a most non-‘Doctor Who’-like ending, albeit one it shares with ‘City of Death‘, one that involves the use of a fist – a punch that saves the universe.

So, “Heaven Sent‘ a beautifully constructed symphony to loss and grief, wrapped up in a structure built from a fairytale and with elements in common with ‘The Prisoner’. A thing of dark, melancholic beauty and hope in the face of seemingly boundless adversity. And quite simply the greatest ‘Doctor Who’ story ever made.

Coda

Life doesn’t follow the usual Steven Moffat narrative structure. It isn’t a dark fairytale, where in the end ‘everybody lives‘ or comes back to life or gets to live on in another form. It isn’t ‘Hell Bent‘, it is rather ‘Heaven Sent‘, where everyone dies and those left behind are left to grieve and to remember those who are gone. In that respect ‘Heaven Sent‘ is the greatest ‘Doctor Who‘ story – based on a fairytale by the Brother’s Grimm, but resolutely adult and unflinching in its depiction of death, mortality, and the numbing sadness of loss and grief. It is brutal in that respect, but also very, very beautiful and life affirming.