‘Where the winds of restlessness blow. Where the fires of greed burn. Where hatred chills the blood. Here, in the depths of the human heart. Here is the Mara.’

So, fresh from a bruising experience where writer Chris Bailey feels that he has seen his story reduced to ‘a cheap spectacle, with poor quality, tawdry production values and themes and scenes inserted just to ‘colour things up’, Bailey writes the 1983 sequel to ‘Kinda’, ‘Snakedance’ about a society that has reduced the story of the Mara to a tawdry spectacle involving plastic pink snakes and funny mirrors. In some ways I think I could probably end the review there.

Anyway, to my mind ‘Snakedance’ is a direct comment on Bailey’s experiences during the writing and production of ‘Kinda’. Much as Panna (wisdom) begat Karuna (compassion) or the dreaming of an unshared mind or the meeting of minds in the great crystal begat the Mara, ‘Kinda’ begat ‘Snakedance’. The whole thing is a circle – a wheel turning or a snake eating its own tail.

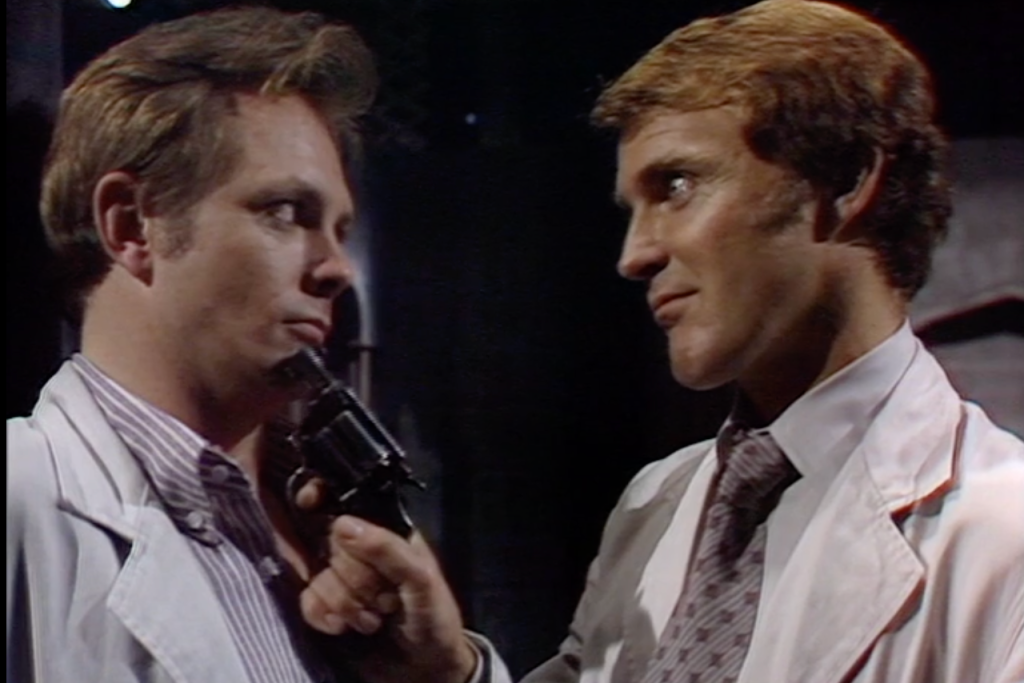

Snakedance is also in some ways as much about refining its parent story, as for example ‘Moonbase’ is to ‘Tenth Planet’. However, as in that example, in the process of refining and ironing out some of the rougher edges of the original story, some of the more interesting, distinctive aspects are also lost. There are a lot of similarities between the two stories. In ‘Kinda’ the Mara was a force returning to a world where it had been previously banished, returning to Deva Loka through the dreaming of Tegan and the despair and temptation of Aris. The 1983 sequel follows a very similar pattern – with the Mara returning to Manussa hundreds of years after being banished and the Doctor and Tegan are once again the vector for its return. We return to themes of regression to childhood and ritual to lessen or absorb the impact of the Mara (the Trickster in Kinda, the re-packaging of the legend of the Mara for commerce or via a ‘Punch and Judy’ show here). We also have telepathy and the shared mind again – the Kinda in the original story and Dojjen and the snake dancers in the sequel. We even have the Doctor treated as a fool or mad man again. The use of mirrors is re-visited and once again we have the ending with the expanding snake, slightly more effective this time, but still with rubber snakes – just brown rather than bright pink.

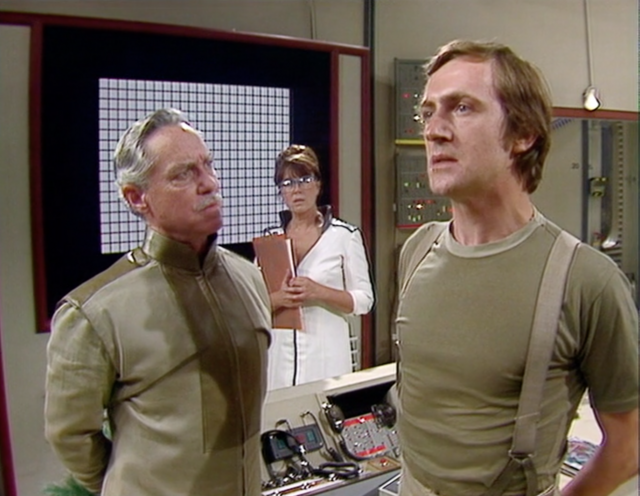

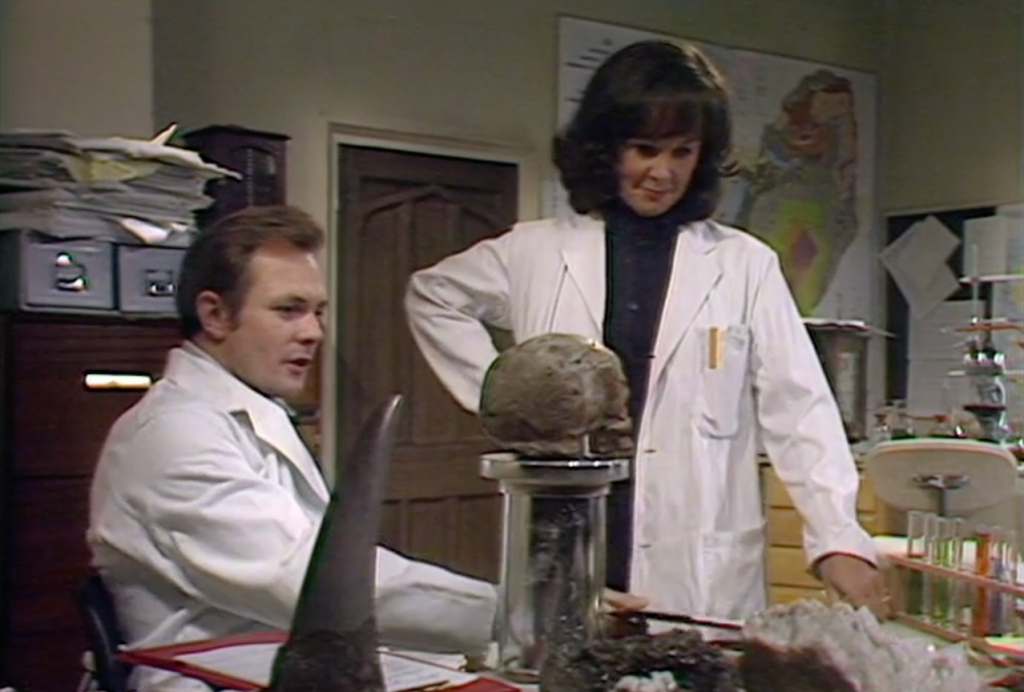

If the plot mechanics and themes are similar, what is different is the world. Manussa is the world of men as opposed to Deva Loka – the world of deities and the cast of characters that populate this world come from a different palette. In ‘Snakedance’ the Mara returns to the world in which it originally came into existence. It is in some ways a ‘Genesis of the Mara’ story, we don’t see the birth, but rather through the origin myth and through archaeologists Ambril and Chela and ‘wiseman’ Dojjen, we hear how it was born and catch it in the process of it’s re-birth.

Manussa – the world of men

‘Manussa, formerly homeworld of the Sumaran Empire which may or may not ring a bell. Does it, Tegan? The Sumaran Empire?‘

So, what is different this time around is the world that Chris Bailey builds. The themes of colonial intrusion present in ‘Kinda’ are lost and are replaced by the weight of history and myth – the past turned into commerce and entertainment. Manussa, as with Deva Loka, is very nicely drawn – a civilisation that has regressed from what it once was, but is still what we would still define as ‘civilised’. It has been through an advanced technological phase (the time when the great crystal and the ‘little minds eye’s were engineered.), through the dark ages when the Mara was unleashed, but back to something that looks like possibly the middle-ages – maybe equivalent to the Moorish civilisation on Earth. It may be more advanced than that – but we don’t, as far as I can remember, see much in the way of advanced technology. So after a period of a post-Mara recovery, it has stagnated for the best part of 500 years, the dark past remembered through sensational stories, in fairgrounds and puppet shows, plastic snakes and bedtime stories to scare the children. The latter feels like a direct commentary on the finished production of ‘Kinda’ to me, if so it slightly misses the point, one of Doctor Who’s core elements is the story of monsters to scare the children – it is part of long tradition, going back far beyond the 54 years of the show itself in that respect.

Manussa is beautifully realised – both via the script and through the production design. However the filmed sequences with Dojjen in the wilderness are far more atmospheric and effective and just serve to point out how much ‘Doctor Who’ loses just through being captured on videotape. I was thinking about this watching it again, I was around 13 when this originally aired and even then I knew there was something special about the sequences with Dojjen out in the wilderness, they looked beautiful and atmospheric, but I didn’t know why. I didn’t know back then the differences in look and feel between film and video – but it was obvious and quite jarring.

The origins of the snake dancers

And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover. (Mark 16:17-18)

In Kinda the Christian symbolism of the serpent was primarily an echo of ‘temptation’ in Eden and was added really to help the largely non-Buddhist audience to understand the basics of the plot. The snake has a wider significance within Christianity beyond that of just temptation. The roots of the sequel lie in the religious practices in the Southern USA – but from two very different beliefs. I think Bailey accidentally conflates the two in his interview for the DVD documentary,

One reference point is the practice of ‘snake handling’ that some fundamentalist Christian churches principally in the Appalachian Mountains. ‘Fundamentalist’ in the sense that they believe in the literal truth of the bible and some use snake handling as a method of showing how God protects them from harm. When it goes wrong, well it was just their time anyway. The motivation comes from the quote from the gospel of Mark above – ‘they shall take up serpents’ – something that they follow literally.

Another influence was a culture that uses snakes in a slightly different way. In Arizona, the Native American Hopi ceremonially dance with snakes on particular occasions. The snakes, as with the Christian snake handlers, are not worshipped, the Hopi believe they are their brothers and that they act as a conduit for prayers for rain to the underworld, where their ancestors reside. For anyone who is interested, the link below is for Library of Congress film from 1913 of the Hopi performing the snake dance for Theodore Roosevelt.

It is worth noting that the Hopi spirits of nature – the Kachina, as with the snake dancers in this story reside for most of the year in the mountains. When dancing in costume the Hopi lose their self, becoming the Kachina that they are dressed as.

‘Oh, they were frightful. They were all covered in ash. Some of them were almost naked. They lived entirely on roots and berries and things, and they put themselves into trances. It was quite disgusting. They handled live snakes, I remember.’

In ‘Snakedance’, the dancers handle the snakes and use their venom presumably to enter a trance like state, echoing shamanic rituals from indigenous peoples around the world that involve a variety of hallucinogens.

‘Well, according to the Legend, the Mara’s return may only be resisted by those of perfectly clear mind. The Dance was a dance of purification in readiness for the return. However, the Federation held that the Mara no longer existed. That’s why they drove the Snake Dancers into the hills. Oh, apparently it involved the use of certain powers.’

‘Certain powers’ might be a reference to the telepathic meeting of minds, but it feels more like a euphemism for the lysergic-like effect of the venom to me.

NYSSA: Doctor, no. What are you doing?

DOCTOR: I’m afraid we have no choice if we’re to have any hope of saving Tegan.

NYSSA: But its bite could be deadly.

DOCTOR: Yes, I do know.

Under the influence of the snake venom the Doctor is able to communicate with Dojjen, although why they couldn’t just have a chat isn’t entirely clear! Something related to the venom as purification?

DOJJEN : No, look into my eyes. You have come this far. You must not now give in to fear. Look.

DOCTOR: It’s the poison. The effect of the poison.

DOJJEN: Fear is the only poison.

DOCTOR: Fear is.

DOJJEN: Ask your question.

DOCTOR: How, how can, I must save Tegan. It was my fault, so how, how can. Destroyed. How can the Mara? It was my fault.

DOJJEN: Steady your mind. Attach to nothing. Let go of your fear.

DOCTOR: What is the Snake Dance?

DOJJEN: This is, here and now. The dance goes on. It is all the dance, everywhere and always. So, find the still point. Only then can the Mara be defeated.

DOCTOR: The still point? The point of safety? A place in the chamber somewhere. Where?

DOJJEN: No, the still point is within yourself, nowhere else. To destroy the Mara you must find the still point. Point. Point. Point. Point.

Still Point – William Blake and T.S.Elliot Literary allusion in Snakedance

Nothing is written in isolation. For this review I didn’t read any previous reviews by posters on here or elsewhere, however some things are just lodged in your brain almost as folk memory. For as long as I can remember, well since 1983 at least, I have known that ‘Snakedance’ was influenced to some degree by William Blake and T.S Eliot, particularly the latter. I think I originally read it in a review in a fanzine called ‘Skaro’. I can’t unlearn that knowledge and when I hear the ceremony of the becoming I immediately think of the ‘Auguries of Innocence’ and ‘The Four Quartets’. Proof in case anyone doubted it that clever, literate people with too much time on their hands have been applying their imagination and analytical skills to ‘Doctor Who’ for as long as fandom has existed, long before people with their internet blogs or threads. Back then they just disseminated their views via the medium of letraset and the Royal Mail.

Across ‘Snakedance’ Chris Bailey borrows some of the imagery and also phrasing of William Blake and T.S. Eliot (perhaps he was a Van Morrison fan – ‘Summertime in England’?) for Snakedance:

‘The first temptation is fear.

I offer you fear in a handful of dust.

The second temptation is to despair.

I offer you despair in a withered branch.

The third and final temptation is to succumb to greed.

Stranger, now you must look into the crystal without greed for knowledge.

I offer you greed in the hidden depths.’

Chris Bailey – Snakedance (1983)

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Wiliam Blake – Auguries of Innocence (1863)

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

T.S Eliot The Wasteland (1922)

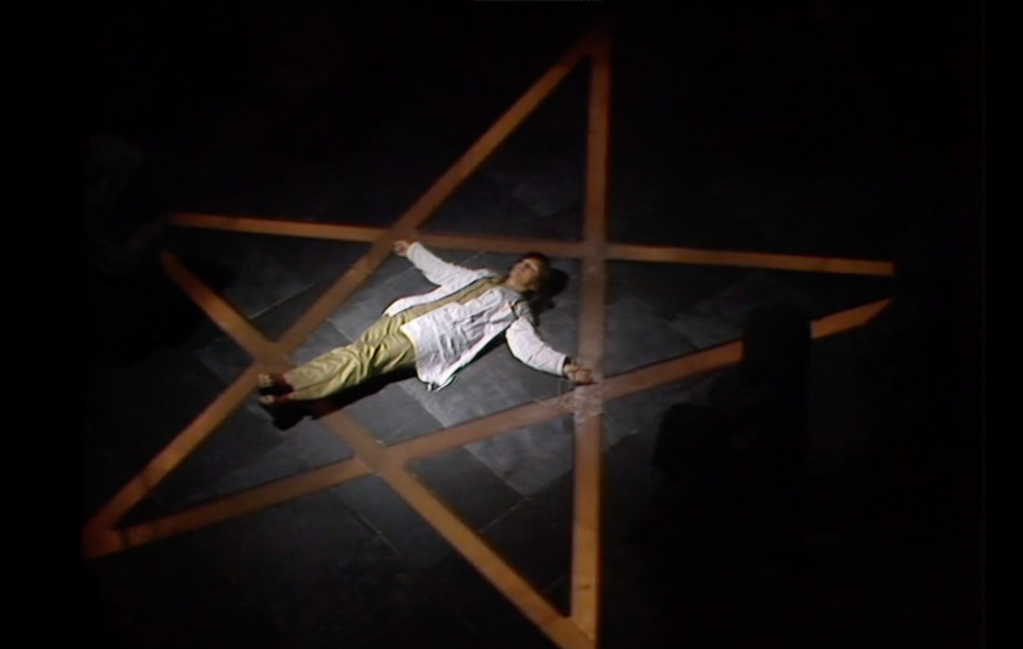

Eliot also crops up again with regard to the meditation of Dojjen and the Doctor out in the wasteland – the concept of ‘finding the still point’ and the dance.

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

T.S.Eliot – The Four Quartets (1943)

The same source aptly sums up the Mara at the end of this story:

Caught in the form of limitation

Between un-being and being.

In fact, ‘The Four Quartets’ is a very apt piece to inspire ‘Snakedance’ – it has a myriad of references to time and repetition and life – birth, death and re-birth, echoing the Great Wheel of ‘Kinda’.

Or say that the end precedes the beginning,

And the end and the beginning were always there

Before the beginning and after the end.

And all is always now.

In my beginning is my end.

In succession Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored,

or in their place is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

If you add in the Buddhist influences on the names on display again here – Tanha (desire or greed), Manussa (world of man) and the snake dancers, it is clear that Bailey isn’t afraid to borrow from very disparate sources to build his world.

Next I will take a look at the cast of characters in ‘Snakedance’, how the story deals with the past and mythology and the themes of regression to childhood.

The Federator’s son is bored.

Watching ‘Snakedance’ as an adult there seems something familiar about it – not the themes or imagery, but more in the structure of the relationships between the characters. It took me a while to realize why I think that is – at first I thought of it as a chamber piece – almost a drawing room comedy of manners, but then a thought came to me – Snakedance almost feels like ‘Doctor Who’ as Chekhov play. Go with me on this one and I will explain my thinking. Chekhov plays have a variation on a series of archetypes – the matriarch (Madame Ranevskaya, Arkadina) the son, the Doctor (!), the student, the teacher, the daughter, the older relatives stuck in the past, the peasants and estate workers. Substitute the cherry orchard or dacha for Manussa and although I’m stretching the point somewhat – we have Tanha (the Mother), Lon (the son), the Doctor, Ambril (the boring teacher), Chela (the student) Nyssa (the young, innocent daughter – a stretch I know) and then the likes of Dugdale and the fortune teller representing the working class/peasant characters.

The feel of the piece is also similar – the wistful evocation of past glories now gone to seed, the sense of boredom/disappointment and frustration, the mother indulging her indolent son, the boring teacher droning on about his subject to the clearly bored audience. The relationship between the aristocrats, professional class and deferential ‘peasants’ just feels structured in a similar way. I am not saying that Bailey consciously echoes these plays, but he is a literate writer and these types of characters and scenarios appear to me to seep into his writing.

The cast of characters in ‘Snakedance’ are beautifully drawn and feel like they genuinely have their own history with each other. For example Colette O’Neil and Martin Clunes genuinely feel like mother and son as a number of people point out in the DVD documentary. There is something almost incestuous about their relationship – she indulges him and he scorns her in return – he is arrogant, selfish, bored, idle and greedy – everything the Mara needs. There are some terrific moments between them and through these we get insights into their family relationships and history:

TANHA: He thought the only people who knew the truth about the Mara were the Snake Dancers. Once he even took us to visit them. It was miles from anywhere, way up in the hills. It was all wildly unofficial. We had to go in disguise. Can you imagine your father in disguise? Even then.

LON: I’m not coming.

TANHA: Good.

LON: I beg your pardon?

TANHA: It’s probably just as well. You’d only spoil it. Your behaviour in the caves this morning was unforgivable. The poor man was quite disconcerted.

LON: Oh.

TANHA: You were taking advantage of your position.

LON: Oh please, you’re going to be dreary.

TANHA: No, I am not going to be anything. We are invited to dinner, I am going. Are you just going to lie there being bored?

LON: Yes, do you know, I rather suspect I am. After all – what else is there to do?

Lon is like a spoiled, self-centred teenager craving something exciting and dangerous in his life – to maybe walk on the wilder side – something he sees in Tegan and the Mara:

DUGDALE: She’s inside.

LON: So I should hope.

LON: You, er, summoned me, apparently. It’s not something I’m accustomed to, but here I am. Well, what happens now?

LON: Yes. After all, why not.

At which point he assumes she is offering him temptation of a different sort, instead she introduces him to the Mara, but there is almost too much in Lon for the Mara to chose from. If the Mara had met the teenage audience of ‘Snakedance’ – myself included – it would have had a field day with endless material to work with. If it unleashes her repressed sexuality, I’m not sure quite what it does to him – even at the start of the story he acts like the Mara has already gone to work on him. What seems to happen is that she dominates him in a way he isn’t used to and offers him excitement, with a hint of sex and danger. All of which contrasts very nicely with what the evening otherwise has to offer – Ambril:

AMBRIL: Then you see, my Lady, we draw a complete blank. It’s quite clear that the Manussans of the pre-Sumaran era were a highly civilised people. Their technology in some senses was considerably in advance of our own. Then, suddenly, almost overnight, the Manussan civilisation simply disappeared. It was certainly subjected to a cultural catastrophe of unimaginable proportions.

TANHA: Shall we eat?

AMBRIL: Yes, to such a n extent that when the Federation record begins some six hundred years later, they speak of the Manussans as a primitive people in thrall to the Mara, sunk in barbarity, degradation and cruelty.

AMBRIL: Are you all right, my Lady?

TANHA: Yes, yes, of course. Please do go on.

AMBRIL: A shame your son could not be with u s.

TANHA: Yes, I’m sure he would have found it all most illuminating.

Lon meanwhile has found his own illumination.

Selling the past

Of course it is. And all so long ago. The Mara was destroyed five hundred years ago and yet we’re still celebrating it. Why?

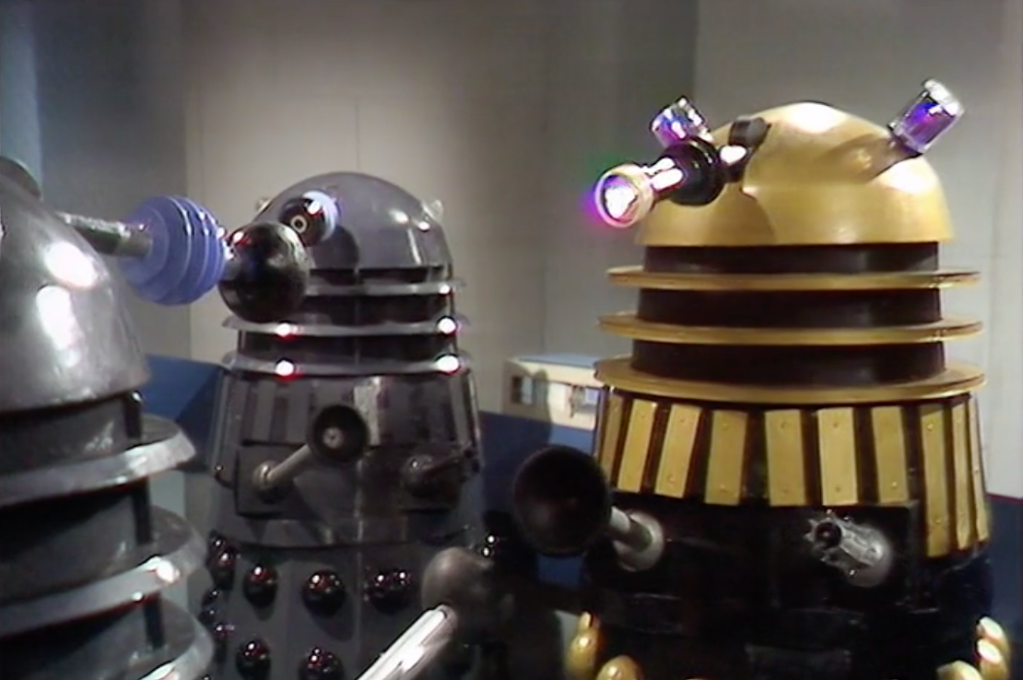

Another aspect covered very well on the DVD documentary is the way ‘Snakedance’ deals with the past. Rob Shearman talks about the way in which all the glories of Manussa are in the past and this is portrayed via a series of cheap, tawdry images for sale. The past packaged for commerce, You see the same in the tourist spots of Britain, try walking the Royal Mile in Edinburgh – a sea of tartan tat, bagpipes and shortbread. Shearman uses this approach in his Big Finish play ‘Jubilee’ (which inspired ‘Dalek’), where the stories of how the ‘English empire’ defeated a Dalek invasion with the Doctor’s help have become cheap, sensational films and a very English festival with bunting. Here the Mara have become a Punch and Judy show, complete with pink plastic snake instead of the crocodile and a cheap booth at a fair, which really just consists of a few distorting mirrors.

‘How about you, sir? Madame, step this way, if you’d be so kind. I invite you to take the most exciting journey of all. The voyage inside. The journey to meet yourself. I address you in the silence of your own hearts. I offer my personal challenge. Dare you bare witness to what the Mara shows? Will you gaze upon the unspeakable? Dare you come face to face with the finally un-faceable? Children half price.’

Brian Miller is fantastic here as Dugdale – that last line ‘Children half price’ is delivered just perfectly. Looking at different aspects of yourself in distorting mirrors is really akin to what the Mara is – it distorts and emphasizes aspects of you – your desire for revenge or greed or power or your repressed sexuality – it reflects and refines that aspect. Here it is reduced to just a cheap thrill in a tawdry fair booth. Likewise we have the fortune teller using the trappings of the Mara and then just making up any old crap that she thinks people want to hear! Again I wonder about that, it feels very much like this is Bailey commenting on the likes of Saward and JNT telling him to ‘colour’ his story with false dramatic cliffhangers and giant pink snakes because it is what they think the children want? Maybe Dugdale – the hawker of cheap thrills to scare children is a direct representation of the Doctor Who production office or how they made Bailey feel during ‘Kinda’?

Next time I’ll wrap this up with some thoughts on regression to childhood, the nature of the Mara and why Snakedance is almost always well reviewed but does surprisingly modestly in polls.

‘I’m in my garden’

Another shared theme with ‘Kinda’ is regression. In ‘Kinda’ we had Sanders regress to a child-like state of innocence after opening the box of jhana, while the mental collapse of Hindle reduced him to a childlike bully, trying to control his own little world whilst keeping the adult world away. In ‘Snakedance’ the Doctor uses hypnotic regression to take Tegan back to Deva Loka and beyond that further back into her childhood:

DOCTOR: Where are you now?

TEGAN: On Deva Loka, the Kinda world.

DOCTOR: What are you doing there?

TEGAN: It’s horrible. Is that thing inside my head? If you must know I climbed a tree and dropped apples on its head. No. I will never agree to what you ask. Doctor? Am I free of the Mara now? Forever? Am I?

DO CTOR: You must go deeper, Tegan. Much deeper. Where are you now?

TEGAN: I’m in my garden, silly. Everything grows in my garden. People always come back. I close my eyes, I want them to come back and they do. It always works. I can tell lies too. People don’t always notice so I’m safe here

DOCTOR: How old are you?

TEGAN: I’m six, silly.

DOCTOR: Tegan, now you must leave your garden.

I thought about this for a while – Tegan safe in her childhood garden – bringing back people that she loves, before being forced to leave it for the harshness of the adult world and to face what is happening to her. That is almost exactly what ‘Doctor Who’ represents for me – a place where I go to undergo a regression to my childhood. Somewhere where a good, moral man fights monsters and stands up to insane dictators and makes the world a better place, somewhere where I am happy in my delusion while I am watching or reading or listening to it. I think I differ from a number of the posters in here, in that I don’t necessarily need it to reflect the real world – society or politics or morality – it is nice if it does, but really I just need it to be clever and interesting and diverting. I am mostly Ok with poorly motivated villains, ‘evil from the dawn of time’ and alien creatures who are just irredeemably bad – just so long as things are clever, work within the fictional world of ‘Doctor Who’ and more than anything make me happy.

I mostly have a nice life – far easier than my parents or grandparents had. Even so, everyone needs somewhere to go sometimes when work or responsibility or a sense of disappointment, ennui or gloom descend. I find that in nature, in photography or in music, but really there is only one place where I can go to where for 25 or 45 minutes I can regress to childhood – bring back the faces of those I’ve lost, return to a time when I am 10 and running down to the newsagents to get ‘Doctor Who Weekly’ or home from school to read my Target book of ‘The Auton Invasion’. A time when the rest of the world can go ¤¤¤¤ itself. Like Tegan, I’m happy in my garden, but after that brief interlude there, I’m afraid it’s time to leave, back to Manussa – the world of men and commerce.

The genesis of the Mara

‘Snakedance’ provides a really rather elegant rationale for the creation of the Mara. The Manussan’s used the little minds eye crystals to meet in the great crystal, where their greed and hatred and all their bad thoughts and desires reflected to create the Mara. Which makes you wonder whether somewhere the opposite of the Mara also exists – created from all of their good and altruistic thoughts and the love that they must have had? I suppose societies create their own gods in their image and that is what happens on Manussa – just literally. I also the love the idea that the Mara, a concept that could just be conceptually evil, quasi-religious or ‘super-natural’ was actually created not just through the desire and greed of the Manussan people, but through their advanced science, the crystals are precisely engineered and manufactured by them to allow function in this way, which is very ‘Doctor Who’:

DOCTOR: Yes, of course, I should have realised. Structurally perfect. It has to be free of all flaws and distortions. Even the minute distortions produced by the effects of gravity.

NYSSA: What are you saying?

DOCTOR: The crystals were designed and built by a people who had mastered the techniques of molecular engineering in a zero gravity environment.

NYSSA: But the Manussans are not that advanced.

DOCTOR: No, and according to Chela this crystal is eight hundred years old.

NYSSA: But there would be records. A people eight hundred years ago capable of molecular engineering?

DOCTOR: Not necessarily. I suspect that when they built the Great Crystal they overlooked one vital factor. The nature of the mental energy would determine the nature of the matter created. The Great Crystal absorbed what was in their minds. The restlessness, the hatred, the greed. Absorbed it, amplified it, reflected it.

NYSSA: And created the Mara.

DOCTOR: Indeed. And in the reign of evil which followed they must have forgotten the most important thing of all, that the Mara was something they themselves had blindly brought into being.

All of which sounds more Christopher H Bidmead than Eric Saward or at least the Saward of legend.

The Mara – possession or body horror?

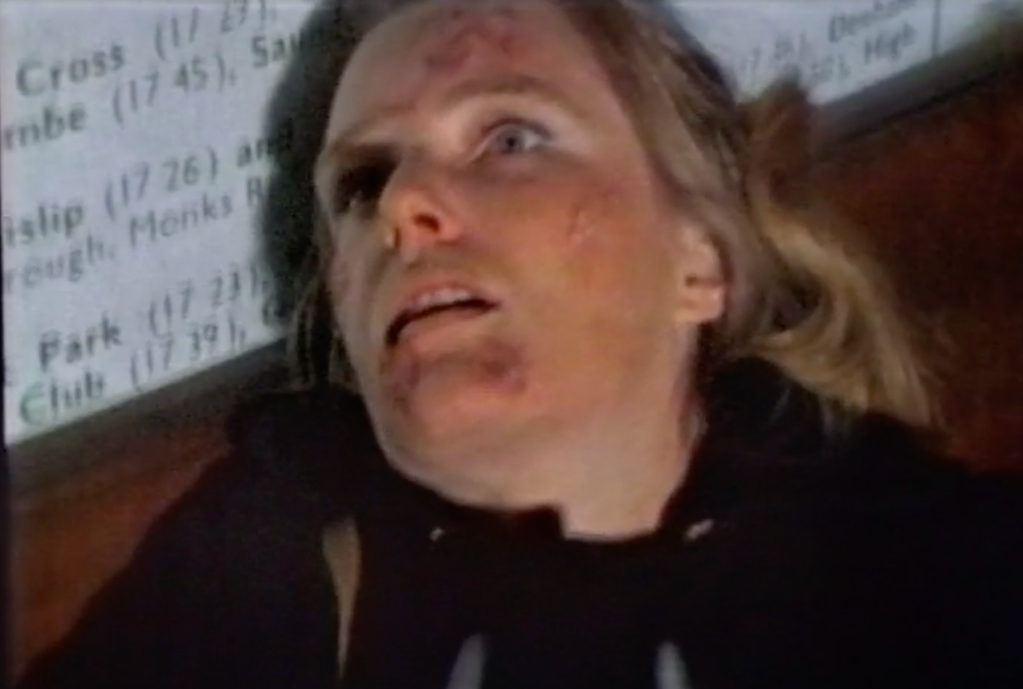

Before I come to the ending, I wanted to say something about the nature of the Mara. Superficially it appears to be another evil force possessing the inhabitants of Deva Loka or Manussa. This is re-enforced by the snake motif passing from arm to arm of those ‘possessed’ by it or Dukhha’s ‘You will agree to being me sooner or later’. Across the two stories we have Tegan, Aris, Lon and Dugdale appearing to be possessed by the Mara. Is this actually the case though – isn’t it more like the Mara unlocks and amplifies an aspect of the person?

It latches onto the worst in you and dials that up to 11. With Aris it is the desire for voice and to avenge the kidnap of his brother. In Tegan it unlocks a playful, sensual, lascivious side of her nature. Lon is already a seething mass of teenage greed, indolence and desires, I’m not sure it quite knows what to do with him. The transformation is less body horror as all it consists of is the snake tattoo, some red teeth and in the case of ‘Snakedance’ some makeup that looks rather like Tegan and Lon have been down to a tanning salon and spent too long under a sunbed. I rather like this explanation for the Mara, you can see it in yourself, calling to you to exploit all your weaknesses, amplifying the worst of you and letting that aspect out into the world.

The sense of an ending

So to the ending, well we slightly amble towards it and ultimately it is a little bit of an anti-climax. The Doctor finding the still point via the teachings of Dojjen or possibly T.S Eliot and trapping the Mara in the act of its becoming is the part that I do really like.

DOCTOR: What is the Snake Dance?

DOJJEN: This is, here and now. The dance goes on. It is all the dance, everywhere and always. So, find the still point. Only then can the Mara be defeated.

DOCTOR: The still point? The point of safety? A place in the chamber somewhere. Where?

DOJJEN: No, the still point is within yourself, nowhere else. To destroy the Mara you must find the still point. Point. Point. Point. Point.

On this viewing the actual realization of the ending seemed rather premature and somewhat bungled, something I must admit I’d never really noticed before. Tegan and Lon are comically red-faced as if fresh from a sauna – Lon really isn’t sporting a good look, combined with ‘that’ costume. The final shot of green vomit pouring out of the mouth of the dead Mara snake is a last attempt by the production team to inject some horror into the programme that it doesn’t especially want it. Then it just sort of stops.

So why isn’t Snakedance more popular?

Snakedance came a relatively modest 112th out of 241 in the DWM 50th anniversary poll. Most reviews I have read over the years have been really positive, so why is this?

There seems to have been a slight shift over the years towards preferring ‘Snakedance’ to “Kinda’. I can see the attraction and ‘Snakedance’ is a more even piece of work, but I think on reflection I prefer “Kinda’. Whilst the performances in the sequel are uniformly good, possibly more subtle than ‘Kinda’ none match that of Simon Rouse and the story isn’t quite as distinctive or interesting. It is a really nice piece of science fiction, with some excellent world building and a thoughtful, reflective script, but it is lacking much in the way of excitement or incident and is very leisurely paced. Which I think might be why it doesn’t rate more highly.

The lack of pace or action wouldn’t really be so much of a problem, if it weren’t also a issue across a range of stories in season 19, 20 and 21. It is something that the show’s star recognises (he says as much) and tries his best to rectify. You can see Peter Davison absolutely working his socks off in his performance here and in other stories – injecting some much needed breathless energy and urgency into proceedings. He is fighting against the script and the pacing of Fiona Cumming’s direction. She does a really decent job here, but doesn’t really manage to build much in the way of excitement or tension, which the script doesn’t entirely help with either. If you want to hear a prime example of Davison really working hard to build the tension and pace of a story, try listening to his reading of the Target novel of ‘Castrovalva’ it is masterclass and really allows you to experience the story in a completely different way. He shouldn’t really need to do this on his own though.

Often the Fifth Doctor’s stories polarize between full on action and violence of which there are only really three examples and then lots of these slower, meandering thoughtful pieces – Castrovavlva, Four to Doomsday, Kinda, Black Orchid, Snakedance, Terminus, Enlightenment, Planet of Fire etc. On reflection, I think that most stories should occupy a better balanced middle ground. The roster of directors – Graeme Harper and Peter Grimwade aside, also do not really help with this – most of them would be happier on ‘All Creature Great and Small’. I also can’t help feeling that in the most truly effective ‘Doctor Who’ stories – the requirements of a family action adventure, horror, sci-fi show (pace, scares, action, big dramatic moments, tension leading to cliffhangers etc.) are balanced and blended with the more thoughtful, clever, intelligent moments. Much as I really love ‘Snakedance’, part of me feels that to fully work, it would possibly need to balance these requirements better.

Ultimately the programme gets an awful lot out of Chris Bailey, but I’m not entirely sure that he wants to be here. The trappings of the show – the requirement for action, incident, dramatic peaks around episode endings and for things to entertain a young audience aren’t really for him. His last story, ‘Children of Seth’ was abandoned twice during the 80’s and was eventually adapted by Marc Platt for Big Finish and makes interesting, typically thoughtful listening – another exercise in world building. His real legacy though are two fine stories which are a gift to review, stories which inspired a generation of us in the early 80’s. Really Chris should have had the opportunity to write interesting, distinctive, fantastical pieces for a more adult single play strand on TV, but it wasn’t to be. A shame really, it was British TV’s loss and that of viewers like me who are still crying out for voices like his to be given opportunities.