The following review was written in Cambridge – in May, but not May week- unfortunately Northern Rail were as confused as the TARDIS – faced with a new timetable boasting more trains, they panicked and decided to cancel most of their existing trains and in fact they now don’t seem to realise that they are supposed to be a train company any more, more that that is an optional extra to the other things they do (mostly cancelling trains). I also failed to persuade my partner to re-create the punting scene on the Cam in front of Kings. Something which I have to say has disappointed me more than it really should:

Wordsworth, Rutherford, Christopher Smart, Andrew Marvel, Judge Jefferies, Owen Chadwick.

Who?

Owen Chadwick. Oh, yes. Some of the greatest labourers in the history of Earth have thought here.

Newton, of course.

Oh, definitely Newton.

For every action, there is a equal and opposite reaction.

That’s right.

Oh, yes. There was no limit to Isaac’s genius.

‘Shadaaaaa’ (old school Tom reference for those who don’t get it!), for a story that never made it to air, it is curiously ubiquitous. I first saw footage from it at a convention in Birmingham 1982, then the clips used on Children in Need night 1983 as part of ‘The Five Doctors’, then large chunks of it were reused in ‘Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency’ (1987), there was the VHS release in 1992, the rather wonderful Big Finish audio with Paul McGann and Lalla and James Fox playing Chronotis (2003), the DVD re-release (2013) and the Gareth Roberts novelisation. (‘Hello Honytonk’ – Gareth channeling Dick Emery in one of the finest reactions to a ‘Doctor Who’ villain ever!) (2012). And so you would think I would know it pretty well by now. With this in mind, when ‘Shada’ came along this time around, I must admit it caught me flat-footed, feeling rather ambivalent. It has taken me a while to buy it and watch it – I thought I knew everything about the story, why did I need another version? Well as it turns out, I was completely wrong and the new Blu-ray is a little thing of wonder and beauty and made me really fall in love with the story. It cheered me up in all of it’s 1979ness and while 1979 might be more of a table wine, sometimes your best times are with a rough bottle of French red and some old friends.

The story of ‘Shada’ and its cancellation are well known and covered very well in the documentaries on this and the DVD release, so I won’t dwell on them. It is such as shame though, whilst I don’t think the story is in the upper echelon of Who stories, it is clever, literate, fun and thoughtful. It manages, like a lot of Douglas’s work, to be very clever and deeply silly at the same time. It would also have rounded off season 17 very nicely, poor old ‘Nightmare of Eden’ and ‘Horns of Nimon’ had their budgets cut to the bone so that ‘Shada’ could be afforded, only to see that cancelled. Graham Williams and Douglas Adams sadly bow out on a partially complete story that can’t be transmitted and a final complete story which was never intended to be a finale which is stylish in places, but desperately cheap and shoddy in others.

The decision to set the story in Cambridge is inspired. It provides a beautiful location, actually on that subject I wonder why ‘Doctor Who hasn’t done this more often – why Bath or Edinburgh or Oxford or other similar British locations have never featured? It also fits in with a story that Douglas Adams apparently once pitched called ‘The Doctor Retires’, re-imagining this story as another eccentric, old Time Lord instead. The choice of location is astute though – Douglas Adams and Cambridge fit each other like a glove, he was born there in 1952, he went to university at St Johns College, graduating (his academic efforts sound rather like the Doctor’s) in 1973. So Cambridge is part of his DNA and it is unsurprising therefore, that when faced with another gap in the schedule to fill, that he would turn to what he knew, imagining that a Tine Lord could easily retire to rooms in a college at the university for hundreds of years without being disturbed.

I’d always imagined that the Doctor would do exactly that – retire like Holmes to his bees in Sussex or Quatermass to the Highlands. The references to Cambridge alumni are a pleasing mix of the obvious and obscure. Just what percentages of internet searches for Owen Chadwick and Christopher Smart are from ‘Doctor Who’ fans do you think? Douglas misses some of the more obvious scientific alumni – Paul Dirac or Roger Penrose (from his own college ), Alan Turing, Watson and Crick or Darwin and from the world of literature his choice is massive Kit Marlowe, E.M Forster, A.E. Houseman through to Terrance Dicks! Can you imagine it :

’Terrance Dicks’

‘Who’

‘Terrance Dicks, one of the great novelisers (sic) of our time. Oh yes there was no end to Uncle Terry’s genius!’

So the plot, well retired Time Lord Professor Chronotis has brought back the ‘Worshipful and Ancient Law of Gallifrey’ back from his home planet and this artefact of Rassillon, possessed of immense powers is now sitting on his bookshelf in his rooms at St Ced’s College Cambridge. Two students – Young Chris Parsons (surely the everyman Douglas Adams representative in this piece) and his friend Claire Keightley (‘it’s Claire’, sigh) are dragged into this world, as Chris accidentally borrows the book. Teutonic, duelling scar sporting sci-fi nutter Skagra is also looking for the book. We get to visit Cambridge, a scientific station in the future, an advanced invisible space ship, two TARDISes, the vortex and the Time Lord’s own prison planet later and a plot that involves possession, mind extraction and an awful lot of tea! I have to say I prefer the scenes in Cambridge, but the bouncing between locations does at least allow the plot to stretch to 6 episodes, as does the sheer brio of Adam’s storytelling and dialogue and the relationship between the Doctor and Romana (or Tom and Lalla for that matter).

Fables of the reconstruction

So what do we gain from the animation/audio reconstruction here? Well most obviously we get the whole story, with the original cast. It tells the story in a way as close to the original intent as is currently possible. In the VHS/DVD release there are big gaps in the story, with bits of narration from Tom, which while entertaining in their own right, mean that we don’t hear or see whole chunks of the story. The animation works fine for this, surprisingly well actually – it never feels jarring for me when the actual footage switches to animation. And well, if techniques and costs improve in the future and there is still interest, at least a full audio recording of the story now exists. The effects are sympathetically done by Mike Tucker and his team, fitting the original footage. The same is true of the incidental music, which feels authentically season 17 – the main cue obviously referencing Dudley Simpson’s work in ‘City of Death’. We also get the bonus of an opportunity to say farewell to Tom in his scruffy, battered, yellowing, but still magical old TARDIS, in his old season 17 costume. Now for a lot of people this won’t mean much, but for the generations that grew up with Tom, it is almost unbearably poignant – more of that in the next part.

Skagra and the Universal Mind

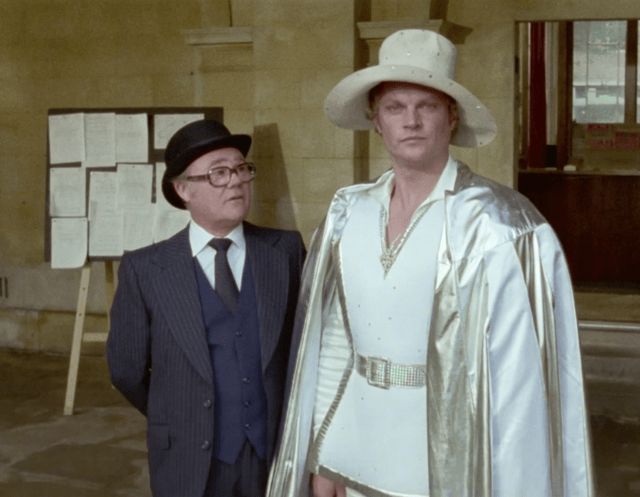

That title sounds rather like a 70’s prog-rock band – which is rather appropriate, since Skagra dresses in a silver/white jumpsuit and cape combination that Rick Wakeman would be proud of – well it is part prog rock parts early 80’s disco – Boney M also sprang to mind (references for the youngsters there!). I love the extra details of the carpet bag and white hat! Part way through Skagra decides he’s had enough of looking like he should be on a Eurovision stage and changes instead into Man at C&A (another youth reference – I’m on fire today – down with the millennials). Christopher Neame though does a surprisingly good job on this – he is hugely camp, vain and arrogant, but he never pushes this too far – dialling it back just enough to fit the tone of the piece and hold his own with the 3 Time Lords here. I can imagine Colin Baker in the role, but maybe going a bit too large – like his turn as Bayban the Butcher in Blake’s 7.

Skagra is apparently a:

‘Geneticist, astroengineer, and cyberneticist, and neurostructuralist, and moral theologian’

Moral theologian – he’s a complete ¤¤¤¤!

Skagra struts his way through the streets of Cambridge in his silver finery and floppy hat, deliberately being setup as the anti-thesis of the Doctor – humourless, nasty, hugely arrogant and representing order and uniformity. His sentient ship is rather nicely done as well, although I preferred the rather breathy Hannah Gordon version from the BF audio. There are some nice moments between the ship and the Doctor ‘Dead man do not require oxygen’ and then her gushing that ‘He has done the most extraordinary things to my circuitry’. His Krargs however are really quite rubbish – fitting in with the overall season 17 vibe of the Mandrells, Erato and Nimon. There is quite a bizarre scene – I don’t know if it just very poorly directed or whether the unfinished nature of the piece plays a part in it, where the Krargs attack the scientists and the Doctor and Chris basically run away, which then cuts to a corridor scene of Chris pulling the Doctor out of the room by his legs. It is just really odd.

‘The universe shall be me’

The book provides the key to Shada – the Tine Lord prison planet. Skagra is working on mind transference and wants to travel to Shada to take the mind of Salyavin, a Time Lord who could transfer his mind into anyone else’s at will. Skagra wants the whole universe to have his mind, to be him and think his thoughts – the ultimate in Aryan supremacy and ethnic cleansing – everyone becoming Skagra and thinking his thoughts. Its’s a pretty scary thought and one thing you can’t accuse Skagra of is failing to think big. In some ways it reminds me of the Master and the immortality gate in ‘The End of Time’ – the whole world replaced by the Master, so maybe it isn’t only Douglas Adams that can re-use his unused ideas.

‘He stole our brains!’

Which is one of my favourite quotes from ‘Doctor Who’ – it is the use of the word brains rather than minds that sounds brilliantly schlocky. Anyway, to facilitate all of this the story features that old ‘Doctor Who’ standby – the machine – in this case the sphere which extracts the mind of it’s victims and then stores them somewhere handy for Skagra to access. Later we’ll even have a mind battle with the Doctor wearing a colander with wires attached, in a similar fashion to ‘Web of Fear‘ or ‘Brain of Morbius‘. Along the way the sphere attacks not only the scientists at Think Tank, the Doctor and Chronotis, but also some poor bloke (who can’t act) fishing and the driver of a car, who Skagra presumably strips of his clothing for his new beige look. More frightening than the sphere or Skagra and his mad plan though is Salyavin and the way he casually takes over and augments Claire’s mind to help jump-start his TARDIS.

PARSONS: Let me just get this right. You say that he just, well, just walked into your mind?

CLARE: Well, sort of. It’s as if he just barged in through the front door and started shuffling all my thoughts about.

He goes from lovely, bumbly, eccentric old Professor Chronotis to Salyavin in an instant – in retrospect that scene rather reminds me of Professor Yana switching straight into the Master in ‘Utopia’, dead fish eyes and all. Salyavin/Chronotis is past all of that though – but it is interesting to see how much of the old Time Lord Criminal is still in there – the eccentric old professor act is just that – an act.

The Ballad of Tom and Lalla

This TARDIS team, are quite wonderful at times, but it is sometimes difficult to know where the Doctor stops and Tom begins and likewise Romana and Lalla. I think they both recognise that now, that the fiction of the show and their real lives just became a bit too entangled together. It works wonderfully on screen though. Although he sometimes complained that the cast took the material too far, Douglas Adams was lucky with the characters and actors that he inherits – Tom and Lalla at this particular moment in time are perfect for this sort of smart, breezy, literate story-telling. Their relationship feels more complete than any of Tom’s other companions – Sarah aside – it is different than that though less best friends and more like partners. It feels like a variation on ‘Doctor Who’s take on Steed and Mrs Peel. Sometimes smart and clever, almost flirtatious sometimes child-like, whatever it is a winning combination.

What is interesting about Tom’s performance in this version of the story, is that in the studio sessions for the additional visual scene, he seems rather infirm and ensure, but when sat down in the audio sessions the sheer force of his personality is almost overwhelming. His voice is steady and clear and he just sounds like his old self, his performance by turns commanding and silly. I shouldn’t be surprised, I listen to most of his Big Finish performances and last saw him in person at Excel in 2013, he was on good form despite looking quite frail in ‘The Day of the Doctor’. Lalla, I last saw reading poetry with Richard Dawkins at Ledbury Poetry festival last year – she always had a slightly superior, forceful, haughty quality to her voice, mixed with the girlish quality that has largely been lost over the years.

I think my new favourite scene in Shada, is the one where the Doctor pins a medal in Romana’s blouse and they salute each other – they look utterly in love at this point – both thinking how wonderful the other is, Lalla/Romana beaming and Tom looking at the camera, as if to say wow, I am one lucky bugger.

In that vein, ‘Lalla – A bit more poise on Saul Bellow!’ is possibly the best stage direction I’ve ever heard! It is very BBC, a time when even cheap sci-fi fare for children was made by intellectuals! The studio sessions are well worth watching, hidden amongst them is something that stirs memories almost as long ago as the cancellation of Shada itself. 1982 I think, when JNT brought the remains of ‘Shada’ to the Panopticon V convention in Birmingham – in my memory they still had the timecode running on them – or maybe I’m mistaken. There is a moment, placed here in the pre-titles sequence, when Caldera and the other Monty Python type scientists are given the stage direction ‘Writhe!’ – cue much twitching and kicking of legs – dying fly style. I can still remember the hall erupting with laughter at that point! It is brilliantly rubbish in a way that only the Graham Williams era can really do. Ramshackle, funny and sometimes very, very clever – it is unique really and the older I get the more I appreciate it.

Claire and Chris

As a neat counterpoint to the Doctor and Romana, we have Claire Keightley and Chris Parsons. Both of whom are very intelligent physics students at Cambridge doing research, but end up mostly running around after our two Time Lords or the Professor looking a bit lost. Or at least until Chronotis upgrades Claire’s mind. Chris, I suspect is Douglas’s identification figure in all of this – his Arthur Dent equivalent, but that slightly gets lost in the TV narrative as this is a story about ‘Doctor Who’, not Chris Parsons. The Gareth Roberts book revolves much more around Chris and Claire and there is quite a bit around their not quite on relationship – of which there are hints in this, for example ’It’s Claire’, sigh as Chris calls her ‘Keightley’. He writes their relationship in a similar manner to Craig and Sophie from his story ‘The Lodger’.

‘Just one little bit of timelessness and spacelessness over there behind the tea trolley.’

Hitchhikers and Dirk Gently both routinely feature the juxtaposition of bizarre science, philosophy and big universal sci-fi concepts against the backdrop of the exceedingly ordinary -tea, towels and sofas wedged in stairwells, council planning departments and telephone sanitisers. And we have that again in ‘Shada’. The Professor’s rooms are actually his TARDIS and the quote above is a prime example of this – the Doctor trapped in Chronotis’s TARDIS gets Claire and Romana to open up a corridor to his own TARDIS, which is being piloted by Skagra – with an entry point just behind the tea trolley. All of which just feels like classic Douglas Adams. This sequence in the old version was set against the background of Tom’s time tunnel title sequence as the space/time vortex – although it didn’t look great, I quite missed that in the new version. The end scenes featuring the policeman, Wilkin and the Professors disappearing room and then the dematerialising TARDIS are another example of this juxtaposition.

Overall, the structure of the story quite reminded me of ‘Stones of Blood’ – it starts out as a story of strange goings on in English location with an eccentric older academic and then switches to something else – a space station in hyperspace or Shada and both have a plot strand around justice and how it is served. If the final episodes of ‘Shada’ had been completed, we would even have had some tatty old monster costumes dragged out of retirement to represent the inmates, again similar to ‘Stones of Blood’ and the prison ship in hyperspace.

Living life trapped with a Doctor Who fan

Ultimately the story is one of the triumph of individualism and plain silliness against uniformity and humourlessness. It is a familiar theme of ‘Doctor Who’ – the replacement of the individual self, of free will and self-determination with order and logic and tyranny – fascism basically. It is a particular theme of the Troughton Era – the Cybermen, Macra or the Master Brain – but it also runs across the history of the series – WOTAN, BOSS or the Infinity Gate. In the end, rather appropriately Skagra isn’t killed or destroyed or placed in a cell in Shada and left to rot – instead he is trapped with a ‘Doctor Who’ fan for eternity. I suspect that our loved one’s might slightly know the feeling!

SHIP: I am very much afraid I can no longer accept your orders. You are an enemy of my Lord the Doctor.

SKAGRA: I am your lord! I built you! Release me, I command you. And launch instantly!

SHIP: Do you know the Doctor well? He is a wonderful, wonderful man. He has done the most extraordinary things to my circuitry.

SKAGRA: Release me!

SHIP: Truly wonderful. If you like, I will tell you all about him.

SKAGRA: Let me out! Let me out!

I was recently wathching The 5ish Doctors, which is rather wonderful. That end scene of ‘Shada’ now reminds me of Colin Baker’s family, locked in, being forced to watch one of his stories! I wonder how much our respective parters feel slightly like that at times. I was struck by the similarly slightly ‘ah bless’ sense of indulging a small, slightly over-enthusiastic child that many partners of Doctor Who fans must have. Anyone else recognise that? Anyway, so instead of universal domination and uniformity and order, Skagra is trapped with someone extolling the virtues of his nemesis – that exponent of individualism, freedom and anarchy – the Doctor, which is almost the exact opposite of what he wanted, rather a fitting end from one of the least appealing of ‘Doctor Who’ villains.

Elsewhere, you suspect that Chris and Claire might possibly get together, Chronotis is alive again and still happily making tea, Wilkin gets to upset a policeman, the Doctor and Romana and their dog are off travelling the universe and all is right with the world. But it isn’t really – dark days are coming for Tom, next time we’ll see him he will be asleep in a deckchair on Brighton beach, looking ill and much older, his hair will have lost its curl, entropy taking effect, Romana will be off making her own way in the universe (as will Lalla) and eventually the Fourth Doctor will die surrounded by young strangers, crushed by a fall from a radio telescope, but all of that is for next year, for now the party is still in full flow.

…But there is more from this release. For one last time, Tom dons the scarf and gives us one last mad speech.

For a generation of us, who grew up loving Tom’s Doctor, that is almost unbearably poignant – it is simultaneously joyful and a slightly sad marker of the passage of time. Redolent of a time when we were all Time Tots – sorry a bit crap that line I know – but I couldn’t resist!

So thanks Douglas, Graham, Tom and Lalla and to all of the team who worked to create and then re-create ‘Shada’ as best they could so many years after it was scrapped. It cheered me up and made me happy for a while and you can’t ask for more than that.